An external abdominal hernia refers to the protrusion of internal organs or tissues from their normal anatomical positions into another area through congenital or acquired weak points, defects, or openings in the abdominal wall. The term "hernia" broadly describes such displacements. Hernias most commonly occur in the abdominal region, with external hernias being the most prevalent type. External abdominal hernias arise when intra-abdominal organs or tissues, along with the parietal peritoneum, protrude toward the body surface through weak points or openings in the abdominal wall. By contrast, internal abdominal hernias form when organs or tissues enter recesses within the abdominal cavity, such as an omental foramen hernia.

Etiology

The two primary causes of external abdominal hernias are reduced abdominal wall strength and increased intra-abdominal pressure.

Reduced Abdominal Wall Strength

Several factors can contribute to decreased abdominal wall strength. Common factors include:

- Weak areas where structures pass through the abdominal wall, such as the spermatic cord or the round ligament of the uterus passing through the inguinal canal, the femoral vessels passing through the femoral canal, and umbilical vessels passing through the umbilical ring.

- Underdevelopment of the linea alba, which may result in weak points in the abdominal wall.

- Poor surgical wound healing, abdominal trauma, infection, abdominal nerve injury, aging, chronic illness, and obesity-associated muscle atrophy also contribute to weakened abdominal walls.

- Additionally, genetic predisposition and long-term smoking may be associated with the occurrence of external hernias.

Increased Intra-Abdominal Pressure

Common causes of increased intra-abdominal pressure include chronic coughing, chronic constipation, difficulty urinating, heavy lifting, ascites, pregnancy, and frequent crying in infants. Although temporary increases in intra-abdominal pressure are common in healthy individuals, hernias are unlikely to develop if the abdominal wall strength remains normal.

Pathological Anatomy

A typical external abdominal hernia consists of the hernia ring, hernia sac, hernia contents, and hernia covering.

Hernia Sac

The hernia sac is a pouch-like protrusion of the parietal peritoneum and consists of a hernia neck and hernia body. The hernia neck, which is the narrowest part of the hernia sac, represents the hernia ring or "hernia gateway," corresponding to the weak or defect area of the abdominal wall. Hernias are often named according to the location of the hernia ring, such as inguinal hernia or femoral hernia.

Hernia Contents

The hernia contents are the abdominal organs or tissues that enter the hernia sac. The small intestine is the most common organ involved, followed by the greater omentum. Other abdominal organs may also enter the hernia sac, but this is less frequent.

Hernia Covering

The hernia covering refers to the layers of tissue external to the hernia sac.

Clinical Types

External abdominal hernias are classified into reducible hernias, irreducible hernias, incarcerated hernias, and strangulated hernias.

Reducible Hernia

A reducible hernia is one in which the hernia contents can easily return to the abdominal cavity.

Irreducible Hernia

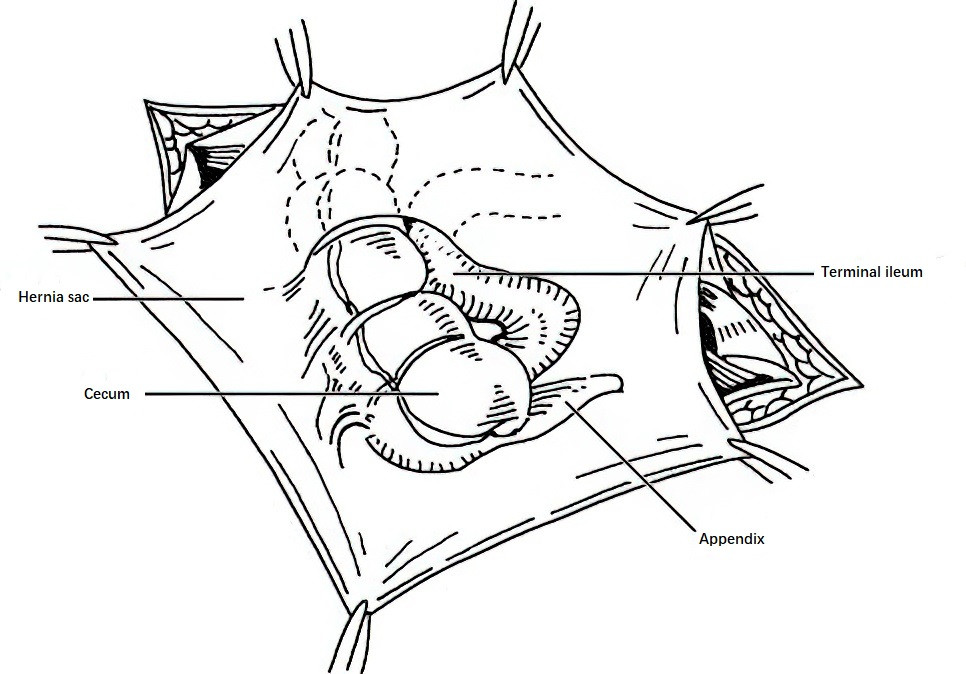

An irreducible hernia is one in which the hernia contents cannot or cannot completely return to the abdominal cavity, although it does not cause severe symptoms. Repeated protrusion of the hernia contents can lead to friction and damage to the hernia sac neck, resulting in adhesions that make the hernia irreducible. Longer-standing hernias may cause additional changes, such as downward displacement of the abdominal peritoneum into the hernia sac due to the pulling force of the hernia contents. This phenomenon is particularly common in the iliac fossa, where the peritoneum is loosely attached to the posterior abdominal wall. In such cases, organs like the cecum (including the appendix), sigmoid colon, or bladder may migrate downward and form part of the hernia sac wall. This type of hernia is referred to as a sliding hernia and is classified as an irreducible hernia. Like reducible hernias, irreducible hernias do not result in vascular insufficiency or significant clinical symptoms.

Figure 1 Sliding hernia, with the cecum forming part of the hernia sac

Incarcerated Hernia

An incarcerated hernia occurs when increased intra-abdominal pressure pushes hernia contents forcefully through a narrow hernia neck into the hernia sac, followed by elastic constriction of the hernia neck, trapping the contents. If the hernia contents include intestinal loops, compression at the hernia neck may impair venous return, leading to intestinal wall congestion and edema. Over time, the intestinal wall and mesentery within the hernia sac thicken, and their color darkens from pale red to deep red. Yellowish exudate may accumulate in the hernia sac, further aggravating the difficulty of hernia reduction. In the case of intestinal incarceration, pulsations of mesenteric arteries may still be palpable. Releasing the incarceration promptly allows the affected intestinal segment to return to normal.

Strangulated Hernia

When an incarcerated intestinal loop is not promptly relieved, progressive compression of the intestinal wall and its mesentery can lead to reduced arterial blood flow, eventually resulting in complete obstruction. This condition is referred to as a strangulated hernia. In such cases, the intestinal wall gradually loses its sheen, elasticity, and peristaltic ability, ultimately becoming necrotic with a blackened appearance. The fluid accumulation within the hernia sac turns pale red or dark red. Secondary infection, if present, can cause the fluid in the hernia sac to become purulent. Severe infection may lead to cellulitis in the covering tissues of the hernia. In some cases, an abscessed hernia sac may rupture spontaneously or be mistakenly incised for drainage, resulting in an intestinal fistula.

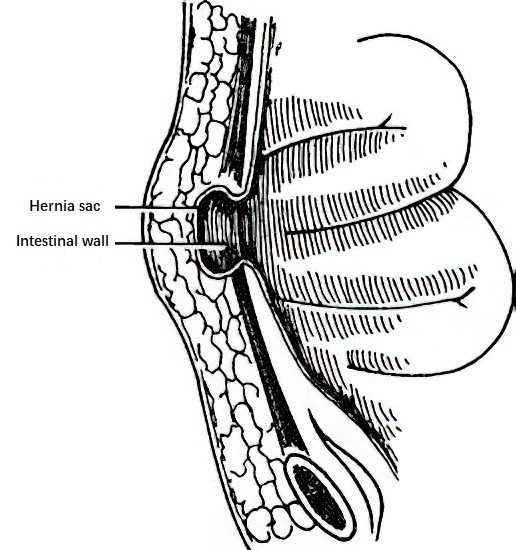

It is often difficult to make a clear clinical distinction between incarcerated hernias and strangulated hernias. Both conditions may cause acute mechanical bowel obstruction. However, in some cases, the incarcerated contents only include a portion of the intestinal wall, while the mesenteric side of the intestinal wall and its mesentery remain outside the hernia sac. In these cases, the intestinal lumen is not completely obstructed. This type of hernia is known as a wall hernia or Richter's hernia. If the incarcerated content is a diverticulum of the small intestine, typically a Meckel’s diverticulum, it is referred to as a Littre’s hernia.

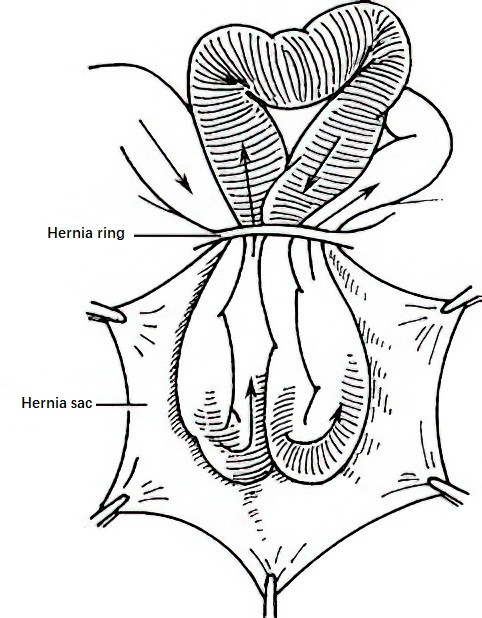

Incarcerated contents often involve a single segment of the intestine. Occasionally, multiple intestinal loops may be incarcerated together in the hernia sac, forming a W-shape, with the segments between incarcerated loops still positioned within the abdominal cavity. This condition is referred to as Maydl's hernia, a type of retrograde incarcerated hernia. In cases of retrograde incarceration with strangulation, not only may the intestine within the hernia sac become necrotic, but the intermediate intestinal loops remaining within the abdominal cavity may also be affected. In rare instances, the intestine in the hernia sac remains viable while the loops in the abdominal cavity have already become necrotic. During surgery for incarcerated or strangulated hernias, retrograde incarceration should be considered. The corresponding intestinal loops within the abdominal cavity should be examined to assess vitality and prevent overlooking any necrotic segments. If the hernia contents include the appendix, the condition is referred to as Amyand’s hernia.

Figure 2 Wall hernia (Richter's hernia)

Figure 3 Retrograde incarcerated hernia (Maydl's hernia)

Hernias in children infrequently develop into strangulated hernias because the tissues around the hernia ring are generally softer and more elastic.

To be continued