The inguinal region is a triangular area located in the anterolateral lower abdominal wall. Its lower boundary is the inguinal ligament, the medial boundary is the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle, and the upper boundary is a horizontal line extending from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis. An inguinal hernia refers to an external abdominal hernia that occurs in this region.

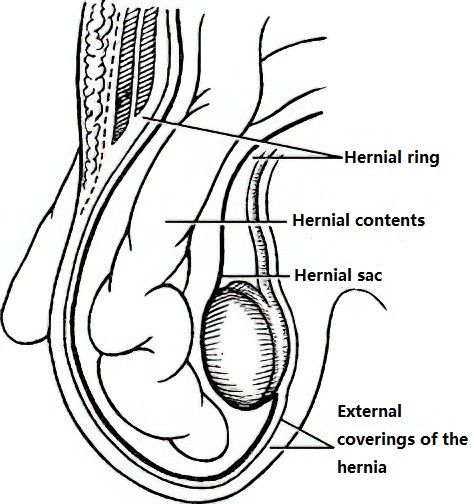

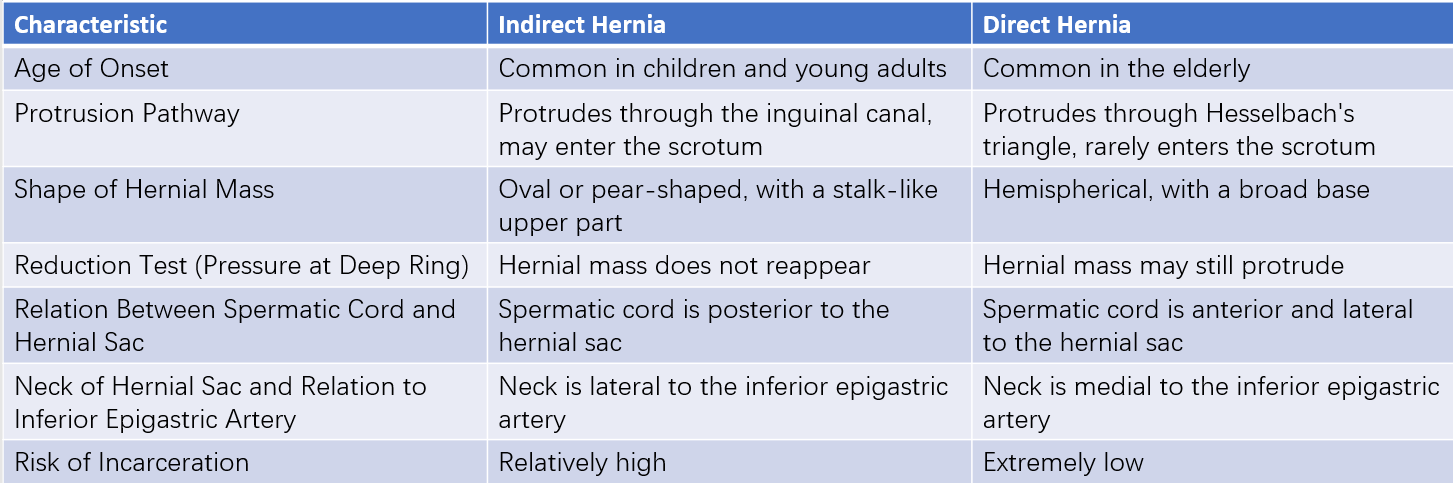

Inguinal hernias are classified into indirect and direct types. An indirect inguinal hernia occurs when the hernial sac protrudes through the deep inguinal ring (internal ring) and travels obliquely inward, downward, and forward through the inguinal canal before exiting the superficial inguinal ring (subcutaneous ring). It may extend into the scrotum. In contrast, a direct inguinal hernia arises when the hernial sac directly protrudes forward through the Hesselbach's triangle without passing through the internal ring or entering the scrotum.

An indirect inguinal hernia is the most common type of external abdominal hernia, accounting for approximately 75%–90% of all cases. It constitutes 85%–95% of all inguinal hernias. The male-to-female ratio of inguinal hernia incidence is approximately 15:1, with the right side being more frequently affected than the left.

Anatomy of the Inguinal Region

Layers of the Inguinal Region

The anatomical layers of the inguinal region, arranged from superficial to deep, are as follows:

Skin, Subcutaneous Tissue, and Superficial Fascia

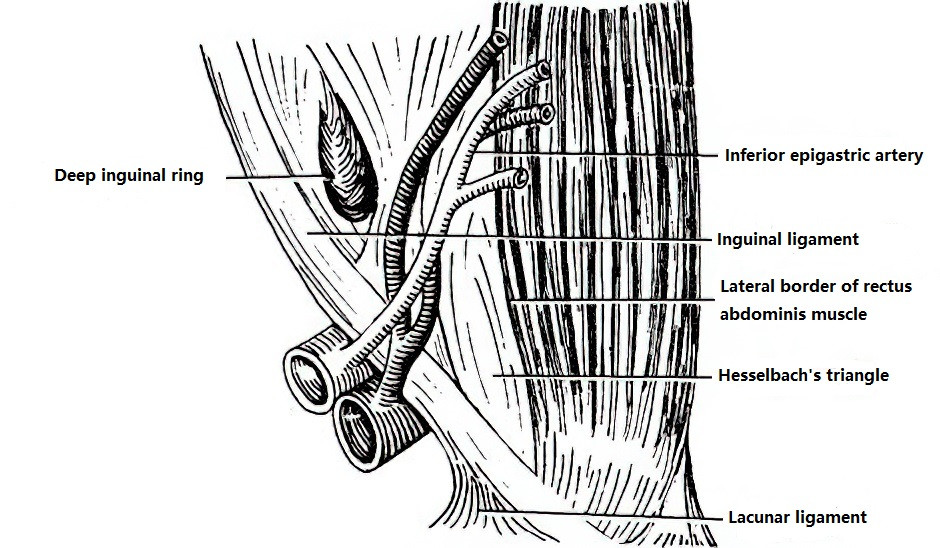

External Oblique Muscle

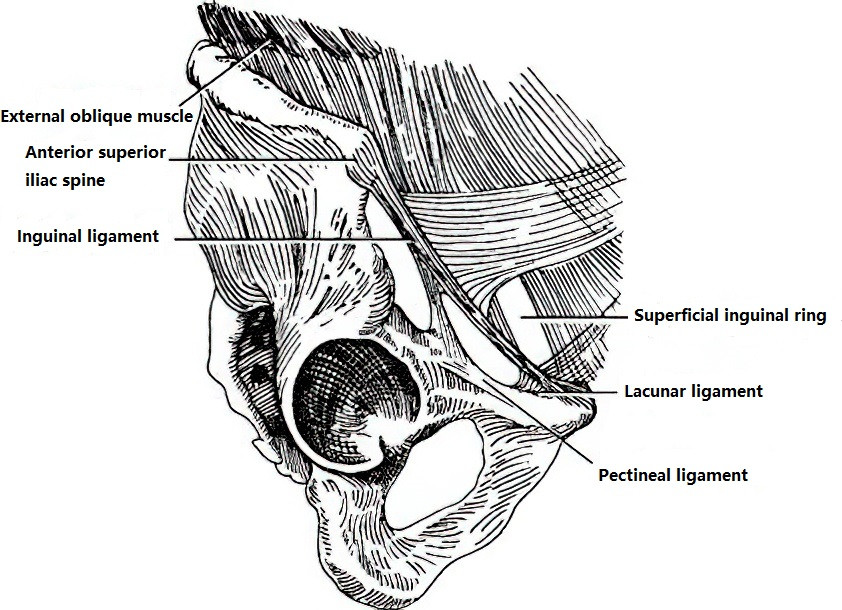

This muscle transitions into an aponeurosis (external oblique aponeurosis) below the line connecting the ASIS and the umbilicus. The lower edge of this aponeurosis folds backward and upward and thickens to form the inguinal ligament, which runs from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle. A small portion of fibers at the medial end of the inguinal ligament turns backward and downward, forming the lacunar ligament (Gimbernat ligament). This fills the angle between the inguinal ligament and the pectineal line, with its margin forming the medial edge of the femoral ring in an arc shape. The lacunar ligament extends laterally and attaches to the pectineal line as the pectineal ligament (Cooper ligament). These ligaments are critical in conventional surgical repair of inguinal hernias.

Figure 1 Ligaments of the inguinal region

Immediately above the pubic tubercle, the fibers of the external oblique aponeurosis form a triangular slit, known as the superficial inguinal ring (external or subcutaneous ring). Between the deep surface of the aponeurosis and the internal oblique muscle, the iliohypogastric nerve and the ilioinguinal nerve pass through this area, which are carefully preserved during hernia surgery.

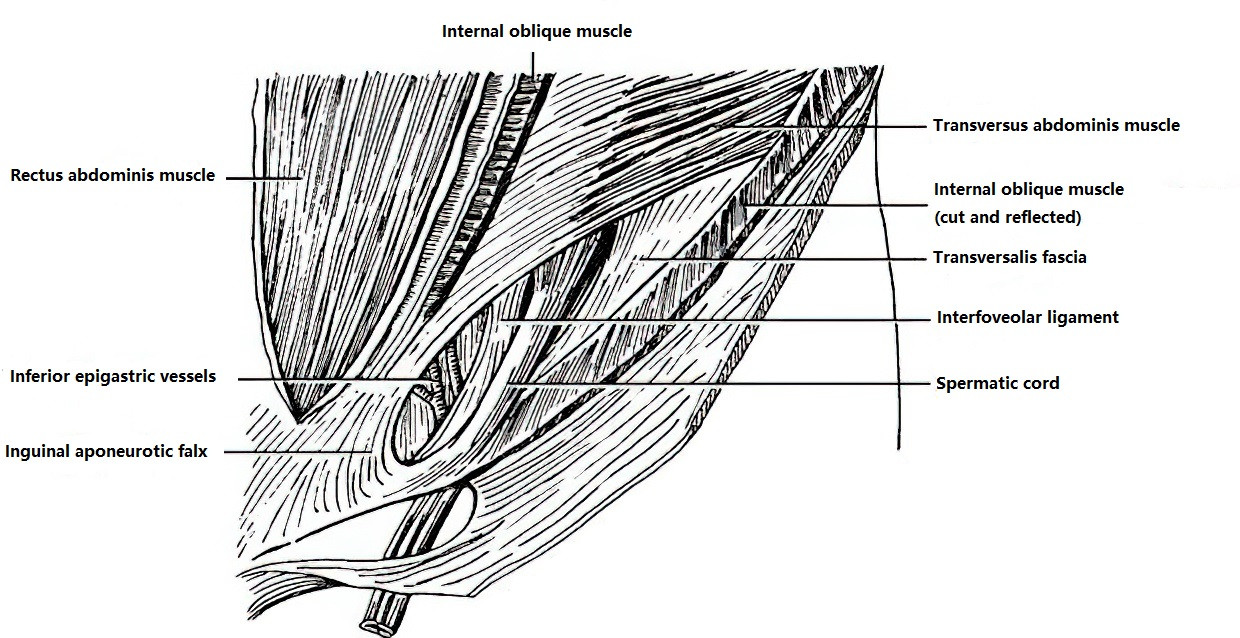

Internal Oblique and Transverse Abdominal Muscles

In this region, the internal oblique muscle originates from the lateral half of the inguinal ligament. The muscle fibers extend obliquely downward and medially, with its lower edge forming an arch as it passes the anterior and superior aspects of the spermatic cord and attaches to the pubic tubercle posteriorly. The transverse abdominal muscle originates from the lateral third of the inguinal ligament, and its lower edge also forms an arch that runs superior to the spermatic cord. It fuses with the internal oblique muscle to form the conjoint tendon (inguinal falx), which also attaches to the pubic tubercle.

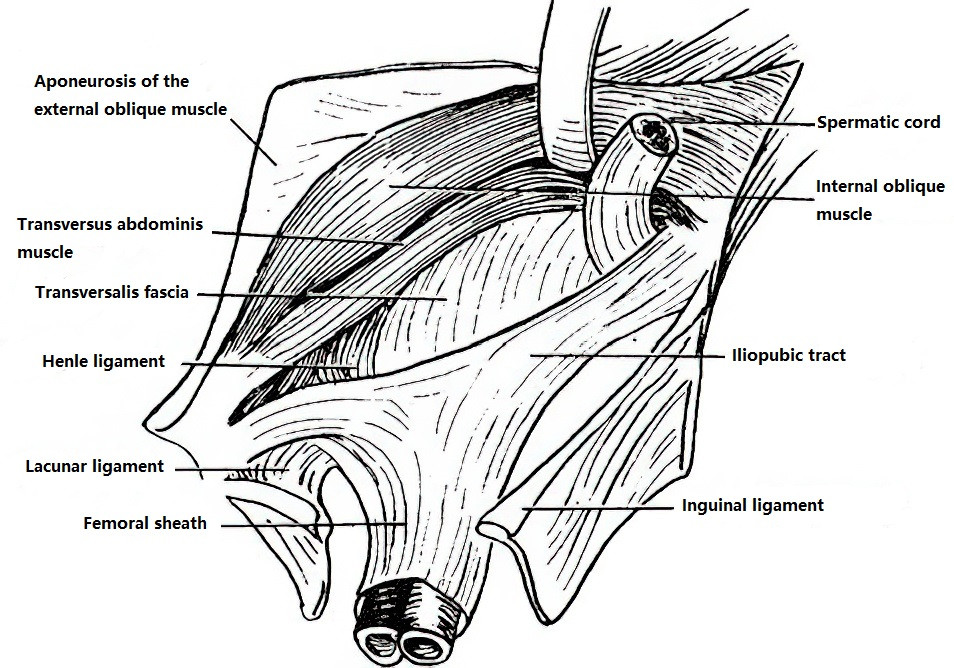

Transversalis Fascia

Located deep to the transverse abdominal muscle, this fascia attaches to the lateral half of the inguinal ligament and, medially, to the pectineal ligament. The lower edge of the fascia thickens as it extends posteriorly from the inguinal ligament, forming the iliopubic tract. Special attention is paid to the transversalis fascia and iliopubic tract in laparoscopic hernia repair. The deep inguinal ring, an oval-shaped gap in the transversalis fascia, is located about 2 cm above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament and lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. The spermatic cord in males and the round ligament of the uterus in females pass through this ring. Below this region, the transversalis fascia surrounds these structures as the internal spermatic fascia. Medial to the deep ring, the transversalis fascia thickens, forming the interfoveolar ligament.

Figure 2 Anatomical location of the iliopubic tract

Figure 3 Anatomical layers of the left inguinal region (Anterior view)

Figure 4 Anatomical layers of the right inguinal region (Posterior view)

Extraperitoneal Fat and Parietal Peritoneum

The anatomical layers highlight a structural weakness in the medial half of the inguinal region. The gap between the arching lower edges of the internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles and the inguinal ligament creates an area where external abdominal hernias are more likely to occur.

Anatomy of the Inguinal Canal

The inguinal canal is located in the anterior abdominal wall above the inguinal ligament. It corresponds to the space between the arching lower edges of the internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles and the inguinal ligament. In adults, the inguinal canal is 4–5 cm in length. Its internal opening is the deep inguinal ring, and its external opening is the superficial inguinal ring, both of which are typically small enough to accommodate a fingertip. Starting at the deep ring, the inguinal canal runs obliquely from lateral to medial, from superior to inferior, and from posterior to anterior. The anterior wall of the canal consists of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and the external oblique aponeurosis, with the lateral third also covered by the internal oblique muscle. The posterior wall consists of the transversalis fascia and peritoneum, with the medial third reinforced by the inguinal falx. The superior wall is formed by the lower arching fibers of the internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles, while the inferior wall consists of the inguinal ligament and the lacunar ligament. The inguinal canal contains the round ligament of the uterus in females and the spermatic cord in males.

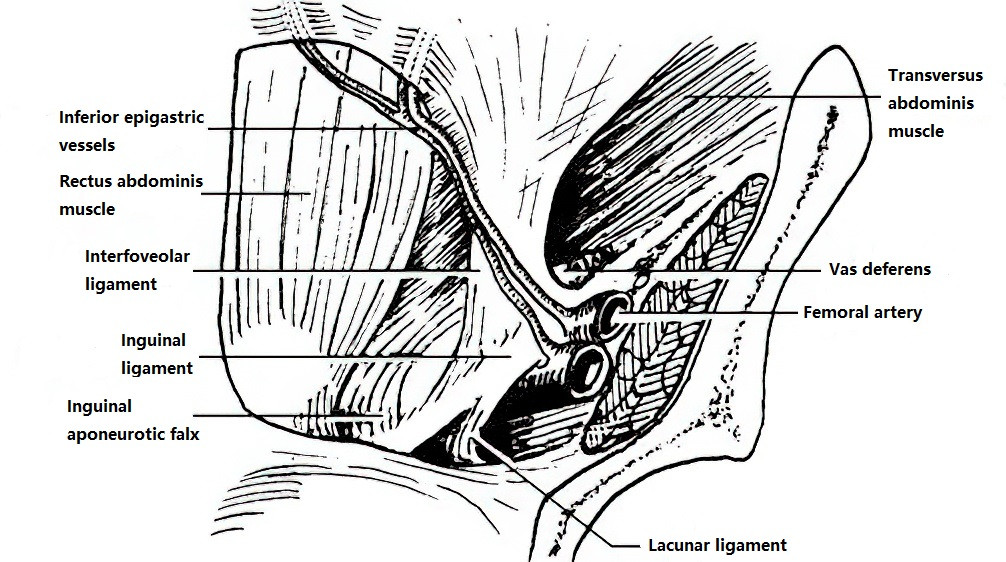

Hesselbach's Triangle (Direct Hernia Triangle)

Hesselbach's triangle is bounded laterally by the inferior epigastric vessels, medially by the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis, and inferiorly by the inguinal ligament. This region lacks coverage from the abdominal muscles and has thinner transversalis fascia compared to surrounding areas, predisposing it to herniation. Direct inguinal hernias protrude through this region anteriorly, giving the triangle its name. Hesselbach's triangle is separated from the deep inguinal ring by the inferior epigastric vessels and the interfoveolar ligament.

Figure 5 Hesselbach's triangle (Posterior view)

Pathogenesis

Indirect inguinal hernia can be classified as congenital or acquired.

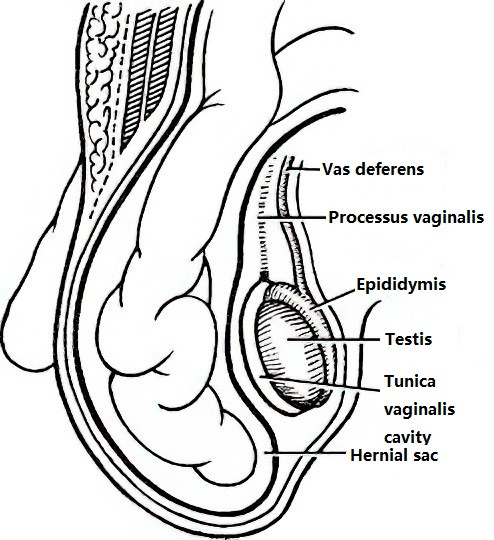

Congenital Anatomical Abnormalities

In the early stages of embryonic development, the testes are located retroperitoneally near the second to third lumbar vertebrae. As development progresses, the testes gradually descend, passing through the deep inguinal ring and tracking the peritoneum, transversalis fascia, and other structures downward through the inguinal canal. This process pushes the skin to eventually form the scrotum. During this descent, the peritoneum forms a tubular projection called the processus vaginalis, with the testes closely adhering to its posterior wall. After birth, the lower portion of the processus vaginalis typically becomes the tunica vaginalis, while the remaining portion naturally atrophies and closes to form a fibrous cord. If the processus vaginalis remains open or incompletely closes, it creates the hernial sac associated with congenital indirect inguinal hernia. Since the descent of the right testis is slightly delayed compared to the left, the closure of the right processus vaginalis also occurs later, making right-sided inguinal hernias more common.

Figure 6 Congenital indirect inguinal hernia

Acquired Weakening or Defects in the Abdominal Wall

In all cases of external abdominal hernias, a certain degree of weakness or defect in the transversalis fascia is present. Additionally, underdevelopment of the internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles plays a significant role in hernia formation. Contraction of the transversalis fascia and the transverse abdominal muscle can pull the interfoveolar ligament upward and laterally, thereby closing the deep inguinal ring beneath the internal oblique muscle. If the transversalis fascia or the transverse abdominal muscle is underdeveloped, the likelihood of hernia formation increases. It is known that, when the abdominal muscles are relaxed, the arching lower borders of these muscles may separate from the inguinal ligament. However, when the internal oblique muscle contracts, these arching fibers straighten and approach the inguinal ligament, providing stronger support to the spermatic cord and the anterior wall of the inguinal canal. Therefore, individuals with poorly developed or unusually high-positioned arching edges of the internal oblique muscle are more likely to develop inguinal hernias, particularly direct hernias.

Figure 7 Acquired indirect inguinal hernia

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The hallmark clinical manifestation of an indirect inguinal hernia is the presence of a bulge in the inguinal region. In some cases, the bulge is small and localized to the deep inguinal ring, making diagnosis more challenging. Once the bulge passes through the superficial inguinal ring and potentially into the scrotum, the diagnosis becomes more apparent. A typical inguinal hernia can be diagnosed based on the patient’s medical history, symptoms, and physical examination. When the diagnosis is unclear, imaging techniques such as ultrasound, CT, or MRI may be utilized for confirmation.

Reducible Indirect Inguinal Hernia

The primary clinical signs include the presence of a bulge in the inguinal region and occasional mild distension but no other significant symptoms. The bulge often becomes noticeable during activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure and is typically pear-shaped with a stalk-like extension, potentially extending into the scrotum or labia majora. The hernia can be reduced by manually pushing the bulge back into the abdominal cavity, often while the patient is in a supine position. Upon reduction, careful palpation of the superficial ring reveals an enlarged opening and weakened abdominal wall. During a coughing test, a thrust sensation can often be felt on the examining finger placed in the superficial ring. Temporarily compressing the deep inguinal ring while the patient stands and coughs prevents the hernial bulge from reappearing; however, the bulge re-emerges as soon as compression is released, protruding obliquely from superolateral to inferomedial. When intestinal loops form part of the hernia, the bulge is soft and smooth, and it resonates with a tympanic sound upon percussion. Resistance may be encountered during reduction, but once the hernia is reduced, the bulge rapidly disappears, often accompanied by a gurgling sound as the intestine re-enters the abdominal cavity. When the omentum is involved as the herniated content, the bulge feels firm, yields dullness on percussion, and reduces more slowly.

Irreducible Indirect Inguinal Hernia

Clinically, besides more pronounced distension, the primary feature of an irreducible hernia is that it cannot be fully reduced, though the herniated contents show no pathological changes.

Sliding Indirect Inguinal Hernia

This type is characterized by irreducibility along with symptoms such as indigestion and constipation. It is more frequently observed on the right side, with a left-to-right incidence ratio of approximately 1:6. Although rare, the hernia contents in sliding hernias may include structures such as the intestine or bladder, which are at risk of accidental incision during hernia repair surgery, warranting particular caution.

Incarcerated Hernia

This condition occurs most commonly in indirect inguinal hernias and presents as a sudden increase in the size of the hernia, with the bulge becoming tense, firm, and painful, and unable to be reduced. When the hernial content is the omentum, localized pain tends to be less pronounced; if intestinal loops are involved, the pain is more severe and may be accompanied by symptoms of mechanical bowel obstruction. Once incarceration occurs, spontaneous reduction is unlikely. If treatment is not provided promptly, the condition can progress to strangulated hernia, posing a life-threatening risk. A Richter hernia (wall-only hernia) often presents with less noticeable local swelling and may not include obvious signs of bowel obstruction, making it easy to overlook.

Strangulated Hernia

This type of hernia typically exhibits severe clinical symptoms. However, when intestinal necrosis with perforation occurs, pain may temporarily subside due to a sudden drop in pressure within the hernial sac, leading to the incorrect assumption of clinical improvement. If the bulge persists despite a reduction in pain, clinical deterioration should still be suspected. Prolonged cases of strangulation may lead to infection of the hernia contents, causing acute cellulitis and complications such as sepsis.

Direct Inguinal Hernia

Direct inguinal hernias are more common in elderly, frail individuals. The main clinical feature is the appearance of a hemispherical bulge on the medial end of the inguinal region, lateral to the pubic tubercle, when the patient is in an upright position. Symptoms such as pain are typically absent. The wide neck of the hernial sac allows these hernias to easily reduce when the patient lies down. Direct inguinal hernias rarely involve the scrotum or lead to incarceration. The hernia contents are usually omentum or small intestine, though the bladder may also enter the hernial sac, forming a sliding direct hernia, which requires increased awareness during surgery.

Although the diagnosis of an inguinal hernia is generally straightforward, distinguishing between indirect and direct types can occasionally pose challenges.

Table 1 Differentiation between indirect and direct inguinal hernias

Differential Diagnosis

Although diagnosing an inguinal hernia is relatively straightforward, it must be differentiated from the following common conditions:

Hydrocele of the Tunica Vaginalis

The mass in hydrocele is confined to the scrotum, and the upper boundary is clearly palpable. On transillumination testing, hydroceles often exhibit light transmission (positive result), whereas hernias do not. However, in young children, hernia masses may also transmit light due to the thinness of tissues. In indirect inguinal hernias, the testicle can be palpated behind the mass. In contrast, in hydrocele, the testicle is surrounded by fluid and cannot be distinctly palpated.

Communicating Hydrocele

The mass appears and gradually enlarges after standing or daily activities. The volume reduces progressively after lying down, sleeping, or applying pressure to the mass. Transillumination testing is usually positive.

Spermatic Cord Hydrocele

The mass is smaller and located within the inguinal canal. Traction on the ipsilateral testicle causes the mass to shift.

Cryptorchidism

Undescended testes within the inguinal canal may be mistaken for a hernia. The mass in cryptorchidism is generally small and can cause a sense of distention or discomfort upon compression. The absence of the testicle in the affected side of the scrotum makes the diagnosis more definitive.

Acute Bowel Obstruction

An incarcerated hernia may be accompanied by acute bowel obstruction. When the patient is obese or the hernia is small, misdiagnosis is more likely, potentially leading to treatment delays or errors.

Other Conditions

Enlarged lymph nodes, arterial or venous aneurysms, and soft tissue tumors should also be considered as part of the differential diagnosis.

Treatment

Without timely treatment, an inguinal hernia can progressively enlarge, worsening damage to the abdominal wall and impairing physical capacity. Indirect inguinal hernias are also prone to incarceration or strangulation, which can pose life-threatening risks. Except in a few specific cases, surgical intervention is typically recommended as early as possible.

Non-Surgical Treatment

For infants under one year of age, surgery is not immediately necessary because abdominal muscles can strengthen with growth, potentially allowing the hernia to resolve spontaneously. A cotton strap or band may be applied to compress the deep inguinal ring, providing the developing abdominal muscles an opportunity to reinforce the abdominal wall.

Figure 8 Technique for using cotton banding

For elderly or frail patients, or those with severe comorbidities that contraindicate surgery, a truss can be used. After reducing the hernia contents during the day, a soft pad on the truss can be placed over the hernial ring to maintain reduction. However, prolonged use of a truss may lead to thickening and scarring of the hernial sac neck, increasing the likelihood of adhesion between the hernia sac and its contents, which raises the risk of incarceration.

Surgical Treatment

The most effective treatment for inguinal hernia is surgical repair. Conditions such as elevated intra-abdominal pressure or diabetes should be managed preoperatively to minimize the risk of recurrence. Surgical approaches can be categorized into three main methods:

Conventional Hernia Repair

The fundamental principles include a high ligation of the hernia sac and reinforcement or repair of the inguinal canal walls.

High Ligation of the Hernia Sac

The neck of the hernia sac is exposed, and high ligation is performed using sutures or a purse-string closure, followed by resection of the sac. High ligation should anatomically reach the level of the internal ring, which can be identified during surgery by preperitoneal fat. For infants, satisfactory outcomes are often achieved with this technique alone, as their abdominal muscles develop strength over time. For strangulated indirect hernias with necrotic bowel and severe local infection, only high ligation is generally performed, with abdominal wall defects addressed in a later surgery.

Reinforcement or Repair of the Inguinal Canal Walls

Adult patients with inguinal hernias often have varying degrees of weakness or defects in the anterior or posterior inguinal canal walls. After high ligation of the hernia sac, reinforcement or repair is needed:

Reinforcing the anterior wall of the inguinal canal: The Ferguson technique is commonly used. The lower edge of the internal oblique muscle and the conjoint tendon are sutured to the inguinal ligament anterior to the spermatic cord, eliminating the gap between the arching lower border of the internal oblique muscle and the inguinal ligament. This method is suitable for cases with intact posterior walls of the inguinal canal and minimal defects in the transversalis fascia.

Four techniques are commonly employed to reinforce the posterior wall of the inguinal canal:

Bassini Repair

The internal oblique muscle and the conjoint tendon are sutured to the inguinal ligament posterior to the spermatic cord, which is then positioned between the internal oblique muscle and the external oblique aponeurosis. This is the most widely used approach.

Halsted Repair

The external oblique aponeurosis is also sutured posterior to the spermatic cord, relocating the spermatic cord to the subcutaneous layer between the external oblique aponeurosis and the skin.

McVay Repair

The internal oblique and conjoint tendon are sutured to the pectineal ligament posterior to the spermatic cord. This method is suitable for severe weakness of the posterior wall and may also be used to repair femoral hernias.

Shouldice Repair

The transversalis fascia is incised upwards from the pubic tubercle to the internal ring, and the layers of the fascias are overlapped and sutured. The lower edge of the outer leaf is sutured to the deep surface of the inner leaf, and the edge of the inner leaf is subsequently sutured to the iliopubic tract to reconstruct a functional internal ring. The lower edge of the internal oblique muscle and the conjoint tendon are then sutured to the inguinal ligament, reinforcing the internal ring and the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. This method has a lower recurrence rate compared to others and is suitable for large adult indirect and direct inguinal hernias. During repair, the superficial ring exposed during the incision of the hernia sac can be reshaped during closure, minimizing its diameter to only allow passage of the spermatic cord.

Tension-Free Hernioplasty

Conventional hernia repair methods are associated with drawbacks such as high suturing tension, post-operative pulling sensations, and pain at the surgical site. Tension-free hernioplasty utilizes synthetic polymer materials for repair without tension, offering advantages such as reduced post-operative pain, faster recovery, and lower recurrence rates. It is currently the principal method of surgical treatment. Hernia repair materials include absorbable, partially absorbable, and non-absorbable types. The implantation of these materials requires strict adherence to aseptic principles. Hernia repair materials are not recommended for use in emergency operations for incarcerated hernias. Non-absorbable materials are also not recommended in procedures where contamination is possible. Common tension-free hernioplasty techniques include:

Flat Mesh Tension-Free Hernia Repair (Lichtenstein Repair)

A properly sized patch is placed on the posterior wall of the inguinal canal.

Plug-and-Patch Tension-Free Hernia Repair (Rutkow Repair)

A cone-shaped mesh plug is inserted into the hernial ring where the hernial sac has been reduced and is secured. Additionally, a shaped patch is placed behind the spermatic cord to reinforce the posterior wall of the inguinal canal.

Giant Prosthetic Reinforcement of the Visceral Sac (GPRVS)

Also referred to as the Stoppa procedure, this involves placing a large patch at the inguinal region to strengthen the transversalis fascia. The patch prevents the visceral sac from protruding, and adhesions between the patch and the peritoneum ultimately achieve the repair. This method is commonly used for complex or recurrent hernias.

Laparoscopic Inguinal Herniorrhaphy (LIHR)

Laparoscopic hernia repair can be performed using four approaches:

Transabdominal Preperitoneal Approach (TAPP)

This method enters the abdominal cavity, making it easier to identify bilateral, complex, or occult hernias. It also facilitates observation and management of incarcerated or irreducible hernias. Key surgical steps include opening the preperitoneal space in the lower abdomen (retropubic space and inguinal space), isolating and addressing the hernia sac, exposing the genital vessels, vas deferens (in men), or the round ligament (in women), and placing a repair material to cover the myopectineal orifice. The boundaries include the rectus abdominis muscle medially, the iliopsoas muscle laterally, the conjoint tendon superiorly, and the pubic ramus and pectineal ligament inferiorly. The repair material must be laid flat, securely fixed, and the peritoneum closed.

Totally Extraperitoneal Approach (TEP)

This method enters directly into the preperitoneal space, avoiding entry into the abdominal cavity and preserving the integrity of the peritoneum. The areas of dissection and repair are similar to those in TAPP. The main advantage of TEP is reduced interference with intra-abdominal organs. Its disadvantage is the limited working space compared to TAPP, making it unsuitable for large, irreducible, or incarcerated hernias.

Intraperitoneal Onlay Mesh Repair (IPOM)

This technique is used in cases where the above two methods are not feasible, but it is not currently recommended as a first-line laparoscopic approach. It involves entering the abdominal cavity, reducing the hernial contents, and covering the hernial ring with a patch. The patch is secured to the abdominal wall using titanium tacks or sutures. The specialized patch used in IPOM differs from those in TAPP and TEP as it typically has two surfaces: a smooth side that faces the intestines and a rough side that contacts the peritoneum. The cost of IPOM patch materials is relatively high, and there is a risk of dislodgment, which could lead to further intra-abdominal adhesions.

Simple Suturing of the Hernial Ring

This technique involves reducing the internal ring with staples or sutures and is only suitable for small indirect hernias in children.

Laparoscopic hernia repair is minimally invasive and offers advantages such as less post-operative pain, faster recovery, lower recurrence rates, and the absence of localized pulling sensations. It is particularly advantageous for repairing bilateral inguinal hernias, especially those involving multiple recurrences or occult hernias.

Management Principles for Incarcerated and Strangulated Hernias

Manual reduction can be attempted under specific conditions for incarcerated hernias:

- Cases where incarceration time is less than 3–4 hours, local tenderness is mild, and there are no signs of peritoneal irritation such as abdominal tenderness or muscle tension.

- Frail elderly patients or those with severe comorbidities where strangulation and necrosis of intestinal loops are not suspected.

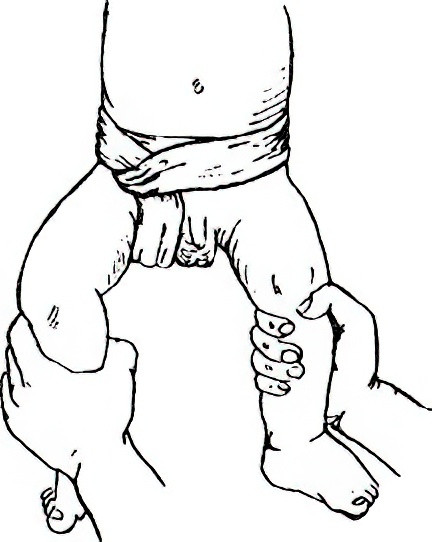

The reduction process involves placing the patient in a head-down and feet-elevated position. Morphine or pethidine is administered to relieve pain, provide sedation, and relax the abdominal muscles. The scrotum is supported with the right hand while the hernial mass is gently and continuously pushed towards the abdominal cavity. With the left hand, gentle massage of the superficial and deep rings aids in the reduction of hernial contents. This method may achieve reduction of early incarcerated indirect hernias, temporarily avoiding surgery. However, risks include the potential rupture of intestinal loops, returning necrotic loops into the abdominal cavity, or incomplete reduction where part of the intestine remains unreduced despite the disappearance of the hernial mass. The procedure must therefore be performed delicately, without forcefulness. Post-reduction, close monitoring of the abdominal condition is essential to identify signs of peritonitis or bowel obstruction. If these signs are observed, surgical exploration should be conducted promptly. Even after successful manual reduction, most patients will require elective surgical repair at a later stage.

In addition to the aforementioned situations, an incarcerated hernia typically requires emergency surgical treatment to prevent necrosis of the hernia contents and to alleviate associated bowel obstruction. Strangulated hernias, with necrotic contents, necessitate immediate surgery. Preoperative preparation, such as prompt fluid resuscitation in cases of dehydration or electrolyte imbalances, is crucial and can directly affect surgical outcomes. The critical aspect of the operation lies in accurately assessing the viability of the hernia contents and determining the appropriate treatment based on the findings.

After releasing the constriction of the hernial ring, intestinal necrosis is confirmed if the bowel appears purplish-black, lacks luster and elasticity, shows no motility when stimulated, and has no arterial pulsations in the associated mesentery. If the bowel is not necrotic, it can be returned to the abdominal cavity and treated as a reducible hernia. When viability is uncertain, injecting 60–80 ml of 0.25–0.5% procaine at the root of its mesentery and covering the affected segment with warm isotonic saline-soaked gauze, or temporarily returning it to the abdominal cavity for 10–20 minutes, can help evaluate viability. If the bowel turns red, regains motility, and mesenteric arterial pulsation resumes, the bowel is considered viable and can be returned to the abdominal cavity. If necrosis is confirmed, or if improvement is not observed after the aforementioned measures, or if viability remains doubtful, resection of the affected section with primary anastomosis should be performed when the patient's overall condition permits. If the patient's condition precludes resection and anastomosis, the necrotic or doubtful bowel segment may be externalized, and an enterostomy can be performed at the proximal segment to relieve obstruction. Bowel resection and anastomosis can be performed 7–14 days later when the patient's condition improves. If the strangulated contents involve the omentum, resection can be performed.

Attention to the following is important during surgical management:

When a large portion of bowel is incarcerated, retrograde incarceration should be suspected. Viability should be assessed not only for the bowel loops within the hernial sac but also for intermediate loops located in the abdominal cavity.

Bowel segments with questionable viability should not be returned to the abdominal cavity.

In some cases of incarcerated or strangulated hernia, hernia contents may spontaneously reduce back into the abdominal cavity due to the effects of anesthesia. If the hernial sac is opened during surgery and no bowel loops are found, careful exploration of the intestines is required to avoid missing necrotic segments in the abdominal cavity. Additional abdominal incisions may be necessary if required.

In patients undergoing bowel resection, due to the contamination of the surgical field, tension-free hernia repair is generally avoided following high ligation of the hernial sac to prevent failure caused by infection.

Treatment Principles for Recurrent Inguinal Hernias

A recurrent inguinal hernia, which occurs after a previous inguinal hernia repair surgery, can be classified into three categories:

True Recurrent Hernia

This is a hernia that reappears at the site of the original surgery due to technical issues or patient-related factors, with the same anatomical location and hernia type as the initial surgery.

Residual Hernia

Also referred to as a concomitant hernia, this occurs when an additional hernia present at the time of the initial surgery is not identified preoperatively or adequately explored intraoperatively, leaving it untreated.

New-Onset Hernia

This occurs after successful repair and thorough exploration during the initial surgery, excluding concomitant hernias. Over time, a new hernia develops, which may have the same or a different hernia type but arises at a different anatomical location.

The latter two types are collectively referred to as "pseudo-recurrent hernias." In clinical practice, distinguishing the specific type of recurrent hernia is not always straightforward and is often unnecessary.

The fundamental requirements for reoperation in cases of recurrent hernia include:

- Surgery performed by experienced surgeons proficient in different types of hernia repair.

- Surgical steps and the repair method determined based on intraoperative findings in each individual case.