Urinary stones (urolithiasis), also known as urinary calculi, are among the most common diseases in urological surgery. Urinary system stones are categorized into upper urinary tract stones and lower urinary tract stones. Upper urinary tract stones include renal calculi and ureteral calculi, while lower urinary tract stones include vesical calculi and urethral calculi. Epidemiological data suggest that 5% to 10% of individuals experience at least one episode of urolithiasis during their lifetime. Upper urinary tract stones occur with similar frequency in males and females, whereas lower urinary tract stones are significantly more common in males. The peak incidence is observed between 25 and 40 years of age.

In the mid-19th century, Simon from Germany successfully performed nephrectomy for the treatment of renal calculi. By the late 19th century, the invention and application of cystoscopy and plain X-ray imaging led to the development of various surgical methods for stone removal. In 1976, Fernström and Johansson from Sweden performed the first percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) to treat renal stones. In 1980, Chaussy from Germany successfully employed extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) to treat urinary stones. The advancements in rigid and flexible ureteroscopy that followed have revolutionized stone treatment, with over 90% of urinary stones now managed without the need for open surgery. Even complex and difficult renal stones can be treated effectively using minimally invasive techniques.

The mechanisms behind urinary stone formation remain incompletely understood, with various theories proposed, including theories of renal calcification plaques, supersaturation crystallization, stone matrix formation, crystal inhibitors, and heterogeneous nucleation. Many studies suggest that urinary stones result from a combination of influencing factors.

Etiology

Various factors contribute to stone formation, including age, sex, ethnicity, genetic predisposition, environment, dietary habits, and occupation. Common causes also include metabolic abnormalities, urinary tract obstruction, infection, foreign bodies, and certain medications. Addressing these issues can reduce the formation and recurrence of stones.

Metabolic Abnormalities

These include:

- Increased excretion of stone-forming substances in urine: Elevated urinary levels of oxalate, calcium, uric acid, or cystine are contributing factors. Increased endogenous oxalate synthesis or heightened intestinal absorption of oxalate may lead to elevated urinary oxalate. Elevated urinary calcium may occur in individuals with prolonged bed rest or hyperparathyroidism. Increased urinary uric acid excretion is observed in gout patients, while familial cystinuria results in increased urinary cystine excretion.

- Changes in urinary pH: Alkaline urine promotes the precipitation of struvite and phosphate, whereas acidic urine encourages the crystallization of uric acid and cystine.

- Reduction in inhibitors of crystal formation and aggregation: Decreased levels of substances such as citrate, pyrophosphate, acidic glycosaminoglycans, and magnesium in the urine can promote stone formation.

- Reduced urine volume: Concentrated urine increases the concentration of salts and organic substances, enhancing the risk of crystallization.

Local Factors

Urinary tract obstruction, infection, and the presence of foreign bodies are significant local factors influencing stone formation. Obstruction can cause infection and promote stone formation, while stones can exacerbate obstruction and increase infection severity. Common obstructive diseases associated with urinary stone formation include mechanical and functional obstructions. Examples of mechanical obstructions include ureteropelvic junction stenosis, bladder neck stenosis, renal or ureteral malformations, ureteral orifice prolapse, renal calyceal diverticula, and horseshoe kidney. Additionally, intrarenal pelvis or calyceal neck stenosis can lead to urinary stasis, promoting renal stone formation. Functional obstructive causes include neurogenic bladder and congenital megaureter, which also lead to urinary stasis and stone formation. Furthermore, bladder outlet obstruction caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia can result in vesical calculi.

Medication-Related Factors

Medication-induced renal stones account for 1% to 2% of cases. Related medications can be classified into two categories:

- Medications that are poorly soluble and highly concentrated in urine: Examples include triamterene, indinavir (used in the treatment of HIV), magnesium silicate, and sulfonamides. These medications can become direct components of the stones.

- Medications that induce stone formation indirectly: Examples include acetazolamide, vitamin D, vitamin C, and corticosteroids. These drugs may alter metabolic pathways, leading to the formation of other types of stones.

Composition and Characteristics

Urinary system stones are typically formed from a mixture of various salts. Calcium oxalate stones are the most common, followed by phosphate, urate, and carbonate stones. Cystine stones are rare. Calcium oxalate stones are hard, difficult to fragment, rough, irregular, mulberry-shaped, and brownish in color. They are easily visible on plain radiographs of the urinary tract. Calcium phosphate and magnesium ammonium phosphate stones are associated with urinary tract infections and obstructions. They are brittle, have rough and irregular surfaces, are often staghorn-shaped, and are grayish-white, yellow, or brown. Layering can be observed on radiographs. Uric acid stones are related to abnormalities in uric acid metabolism. They are hard, smooth, often granular in form, and yellow or reddish-brown in color. Pure uric acid stones are radiolucent on plain radiographs, making them negative stones. Cystine stones result from a rare familial hereditary condition. They are hard, smooth, waxy, and range from pale yellow to yellowish-brown. These stones are also radiolucent on plain radiographs.

Pathophysiology

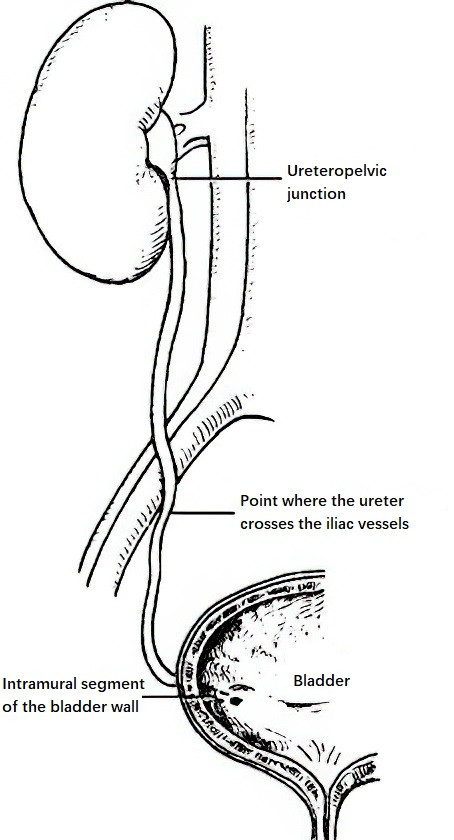

Urinary stones form in the kidneys and bladder. Most ureteral and urethral stones originate from stones formed elsewhere, which become lodged during the process of passing through the urinary tract. The ureter has three natural points of narrowing: the ureteropelvic junction, the point where the ureter crosses the iliac vessels, and the intramural segment at the bladder wall. Stones traveling along the ureter frequently lodge or become impacted at these three natural narrowing points, with the distal third of the ureter being the most common site.

Figure 1 Natural narrowing points of the ureter

Urinary system stones can cause direct trauma to the urinary tract, obstruction, infection, or malignant transformation. These pathophysiological changes depend on factors such as the location, size, and number of stones, as well as the extent of secondary inflammation and obstruction.

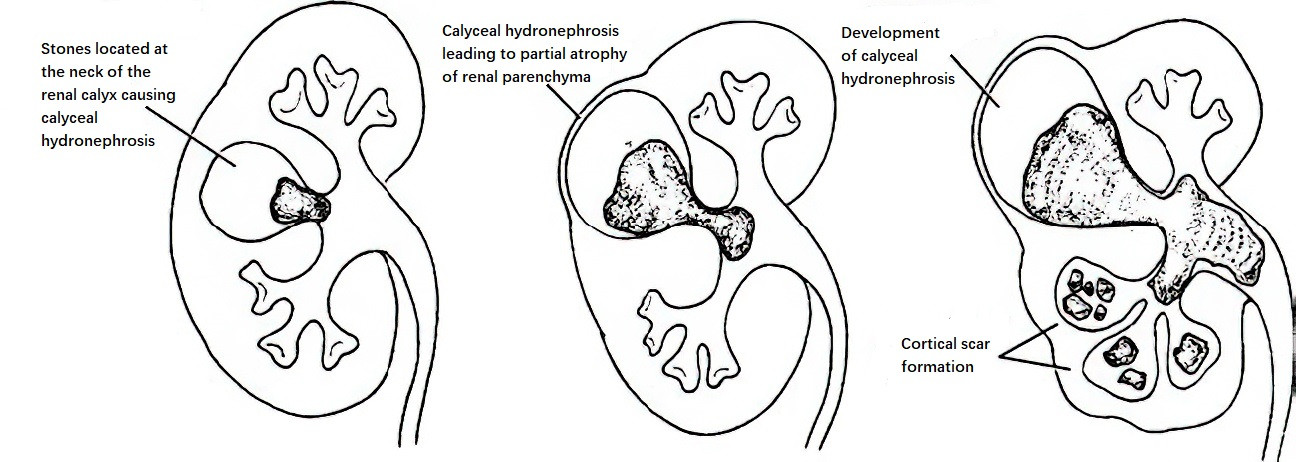

Renal stones commonly originate in the renal calyces and enlarge, extending into the renal pelvis. Stones that obstruct the neck of a renal calyx can lead to calyceal hydronephrosis or pyonephrosis, progressively causing renal parenchymal atrophy, scar formation, and even perirenal infection. Renal calyceal stones that migrate into the renal pelvis or ureter may either pass spontaneously or lodge at any point in the urinary tract. Stones that obstruct the ureteropelvic junction or ureter can cause acute complete urinary obstruction or chronic partial urinary obstruction. Acute obstruction, if relieved in time, does not impair renal function, whereas chronic obstruction often leads to progressive hydronephrosis, renal parenchymal damage, and renal insufficiency.

Figure 2 Progression of renal calyceal stones

Renal calyceal stones may slowly enlarge to fill the renal pelvis and part or all of the calyces, forming staghorn calculi. Stones may be accompanied by infection but can also remain asymptomatic. In rare cases, they may lead to secondary malignancy.

To be continued