Clinical Manifestations

Kidney and ureteral stones are classified as upper urinary tract stones. The primary symptoms include pain and hematuria. The severity of symptoms can vary depending on the stone’s location, size, mobility, and whether there is associated injury, infection, or obstruction.

Pain

Kidney stones can cause flank pain accompanied by percussion tenderness at the costovertebral angle. Large stones in the renal pelvis or calyces may be asymptomatic, though dull pain in the upper abdominal or lumbar region can occasionally occur after physical activity. Ureteral stones can cause renal colic or ureteral colic. Typical symptoms include severe and unbearable intermittent pain located in the lumbar or upper abdominal region, radiating along the ureter to the ipsilateral groin. The pain can also radiate to the ipsilateral testicle or labia. Stones located in the ureterovesical junction may cause bladder irritation symptoms as well as referred pain to the urethra and penile glans. Renal colic commonly occurs when stones are mobile and cause ureteral obstruction.

Hematuria

Hematuria is often microscopic, but gross hematuria may occur in some patients. Microscopic hematuria after physical activity can be the only clinical manifestation in some upper urinary tract stone cases. The amount of blood in the urine correlates with the extent of mucosal injury caused by the stone. If a stone causes complete urinary obstruction or remains immobile (e.g., small stones in the renal calyx), hematuria may not be present.

Nausea and Vomiting

These symptoms often accompany renal colic. When ureteral stones cause urinary obstruction, intracavitary pressure in the ureter increases, leading to local distension, spasm, and ischemia of the ureteral wall. Shared nerve innervation between the ureter and the gastrointestinal tract can result in nausea and vomiting.

Bladder Irritation Symptoms

Bladder irritation may occur in the presence of infection or if the stone is located in the ureterovesical junction. Symptoms include frequent urination, urgency, and dysuria.

Complications and Associated Manifestations

Stones can lead to acute pyelonephritis or pyonephrosis, presenting with systemic symptoms such as chills, fever, and rigors. Stones may also cause hydronephrosis. Severe hydronephrosis may result in a palpable enlarged kidney in the upper abdominal region. Bilateral upper urinary tract stones causing complete bilateral obstruction or complete obstruction of a solitary kidney can result in anuria and uremia. In children with upper urinary tract stones, urinary tract infection is often a primary manifestation.

Diagnosis

History and Physical Examination

Pain and hematuria related to physical activity contribute to diagnostic accuracy, especially in cases of typical renal colic. A detailed history should include details of the first occurrence of symptoms, the nature and radiation of the pain, prior history of stones, family history of stones, and past medical history, including genitourinary disorders, anatomical abnormalities, or factors contributing to stone formation. Percussion tenderness in the kidney area is commonly noted during episodes of pain. The physical examination primarily focuses on ruling out other causes of abdominal pain, such as acute appendicitis, ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion, acute cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, or pyelonephritis.

Laboratory Tests

Blood Analysis

Blood tests should include a complete blood count, serum calcium, potassium, uric acid, and creatinine.

Urinalysis

Hematuria, either gross or microscopic, is often detected. Pyuria is present if there is infection, and urine bacterial and fungal cultures should be performed for patients with infectious stones. Urinalysis can also measure urine pH, calcium, phosphorus, uric acid, and oxalate levels.

Stone Composition Analysis

This is a definitive method to determine the composition of the stone and plays an important role in establishing prevention strategies and selecting dissolution therapy. Analytical techniques include physical and chemical methods, with physical methods such as infrared spectroscopy being commonly used.

Imaging Examinations

Ultrasound

As a non-invasive examination, ultrasound serves as the primary imaging modality. It can detect hyperechoic stones with posterior acoustic shadowing and show associated findings such as hydronephrosis and renal parenchymal atrophy due to obstruction. It is capable of identifying small stones and radiolucent stones that cannot be visualized on a plain radiograph (KUB). Ultrasound is suitable for all patients, including pregnant women, children, individuals with renal insufficiency, and those allergic to contrast agents. However, in some obese patients or cases where the stone location is obscured by pelvic bones, ultrasound may fail to detect stones.

X-ray Examination

KUB (Kidney-Ureter-Bladder Radiograph)

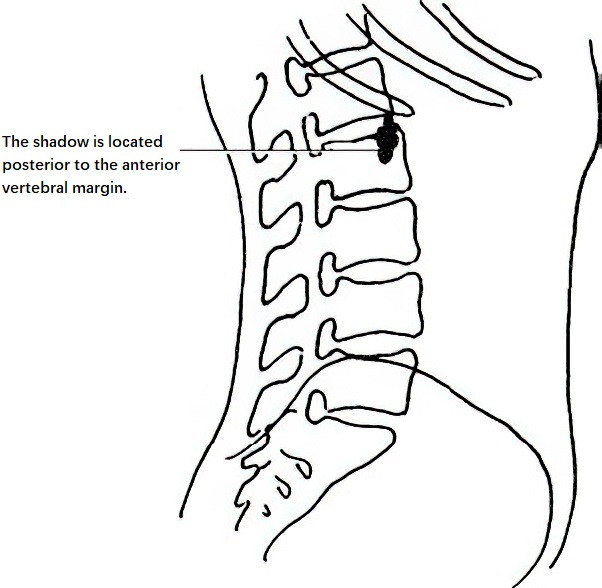

Over 90% of radiopaque stones are identifiable with KUB. Frontal and lateral views can help differentiate stones from other calcifications in the abdomen, such as gallstones, mesenteric lymph node calcifications, and phleboliths. Lateral radiographs typically demonstrate that upper urinary tract stones are located posterior to the vertebral bodies, while intra-abdominal calcifications are anterior to the vertebral bodies. Small stones, stones with low calcium content, or radiolucent stones (such as pure uric acid or cystine stones) may not be visible on KUB.

Figure 1 Kidney stone X-ray (Lateral view)

Intravenous Urography (IVU)

IVU can assess structural and functional changes in the kidney caused by stones, as well as detect urinary tract abnormalities (e.g., congenital anomalies) that may contribute to stone formation. Filling defects can suggest the presence of radiolucent stones or other conditions such as polyps or renal pelvic tumors. IVU can help clarify anatomical abnormalities, such as at the ureteropelvic junction or ureter, which is helpful in forming a treatment plan.

Retrograde Pyelography or Percutaneous Nephrostography

As invasive procedures, these are typically not used as initial diagnostic methods. They are employed when other methods fail to definitively determine the location of stones or when additional urinary tract conditions below the stone require differential diagnosis.

Non-Contrast CT

This examination can detect ureteral stones that are too small to be visualized with other methods. It can differentiate radiolucent stones from tumors, blood clots, or other abnormalities and identify renal anomalies. Non-contrast CT has become a widely used imaging modality for urinary tract stones due to the advancements in imaging technology.

Contrast-Enhanced CT

This method can reveal the degree of hydronephrosis and the thickness of the renal parenchyma, reflecting changes in renal function. Additionally, in cases of suspected hyperparathyroidism, imaging of the parathyroid glands, such as neck ultrasound, may be performed.

Magnetic Resonance Urography (MRU)

MRI cannot directly detect urinary stones and is therefore not commonly used for this purpose. However, MRU can evaluate post-obstructive hydronephrosis without the use of contrast agents, providing imaging results similar to IVU and unaffected by renal function. Thus, MRU can be considered as an alternative for patients unsuitable for IVU, such as those with contrast allergies, severe renal impairment, children, or pregnant women.

Radionuclide Renal Imaging

Radionuclide imaging cannot directly detect urinary stones but is used to assess differential renal function, evaluate pre-treatment renal function, and monitor post-treatment renal recovery.

Endoscopic Examination

This category includes percutaneous nephroscopy, rigid and flexible ureteroscopy, and cystoscopy. Endoscopy not only facilitates diagnosis but also allows for concurrent treatment.

Treatment

The treatment of urinary stones varies due to the complexity and diversity of the stones themselves, differences in stone characteristics (composition, shape, size, and location), and patient-specific factors. Treatment choices and outcomes differ significantly. Some stones are expelled naturally through increased fluid intake, while others require multiple treatment modalities but may not be completely removed. Effective treatment of urinary stones requires an individualized approach, and in some cases, a combination of therapies is necessary.

Etiological Treatment

For certain patients with a clear cause of stone formation, addressing the underlying condition is essential. For example, stones caused by hyperparathyroidism, primarily due to parathyroid adenomas, require surgical removal of adenomas to prevent recurrence. For patients with urinary obstruction, relieving the obstruction is necessary to avoid stone recurrence.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological treatment is appropriate for stones with a diameter of less than 0.6 cm, with smooth surfaces, and without obstructions in the urinary tract below the stone. Pure uric acid stones and cystine stones may be treated with dissolution therapy. For uric acid stones, alkalinization of urine can be achieved through potassium sodium hydrogen citrate, sodium bicarbonate, allopurinol, and dietary modifications, all of which provide good efficacy. Treatment of cystine stones involves alkalinizing urine to maintain a pH above 7.8 and increasing fluid intake. Medications such as α-mercaptopropionylglycine (α-MPG) and acetylcysteine have dissolution effects, while captopril can help prevent cystine stone formation. Infectious stones require infection control with oral ammonium chloride to acidify the urine and urease inhibitors to prevent stone growth. Reducing dietary phosphate intake along with aluminum hydroxide gel can decrease intestinal phosphate absorption and help prevent stone recurrence.

During pharmacological treatment, fluid intake should also be increased to promote greater urine output. Renal colic, a common urological emergency, requires urgent management. Differential diagnosis with other acute abdominal conditions is essential before administering treatment. The primary aim in treating renal colic is to relieve spasms and pain. Commonly used pain relievers include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as diclofenac sodium and indomethacin) and opioid analgesics (such as pethidine and tramadol). Antispasmodic drugs such as muscarinic receptor antagonists, calcium channel blockers, and progesterone may also be utilized.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL)

Stone localization relies on X-ray or ultrasound imaging, after which focused shock waves are used to fragment the stone into fine particles, which are then excreted with urine. This method is applicable for most upper urinary tract stones.

Indications

ESWL is suitable for kidney stones and upper ureteral stones with a diameter of ≤2 cm. The success rate for treating middle and lower ureteral stones is lower compared to ureteroscopic stone removal.

Contraindications

Contraindications include distal urinary tract obstruction, pregnancy, bleeding disorders, severe cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, aortic or renal artery aneurysms, and uncontrolled urinary tract infections. Technical limitations also make ESWL unsuitable for cases involving excessive obesity, high-positioned kidneys, severe skeletal deformities, or unclear stone localization.

Efficacy

The treatment outcome depends on factors such as stone location, size, characteristics, and whether the stone is impacted. Large stones without associated hydronephrosis show reduced efficacy due to limited fragmentation space and often require multiple ESWL sessions. Stones composed of cystine or calcium oxalate are harder and more resistant to fragmentation. Stones in the ureter that have been present for a long time, are impacted, or are associated with polyps are also difficult to fragment.

Complications

Most patients experience transient gross hematuria after ESWL, which usually does not require specific treatment. Perirenal hematoma is rare and can typically be managed conservatively. In patients with infectious stones or stones complicated by infection, complications such as pyelogenic sepsis may occur due to bacterial spread from stone fragments, high intrapelvic pressure caused by obstruction, or renal tissue damage from shock waves. These complications can progress rapidly, potentially leading to septic shock or death, and require prompt treatment. During stone fragment passage, renal colic may occur due to the movement of fragments. If excessive stone debris accumulates in the ureter, it can form a "stone street," causing flank pain or discomfort and possibly leading to secondary infections. The use of low-energy treatments and limiting the number of shock waves per session can help reduce complications. When repeated sessions are needed, an interval of 10 to 14 days is recommended. The total number of ESWL treatments should not exceed 3–5 sessions.

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

PCNL involves ultrasound or X-ray guidance to create a percutaneous tract from the back to the kidney, specifically the renal calyx or pelvis. Through this tract, stones are removed or fragmented using laser, ultrasound, or pneumatic lithotripsy. PCNL is used for kidney stones requiring surgical intervention, including complete and incomplete staghorn stones, kidney stones ≥2 cm in diameter, symptomatic calyceal or diverticular stones, and stones resistant to or unresponsive to ESWL. It is also suitable for larger upper ureteral stones located above the fourth lumbar vertebra. Conditions such as coagulopathy, excessive obesity that prevents puncture access, and severe spinal deformities make PCNL unsuitable.

Complications include renal parenchyma tear or perforation, bleeding, urinary leakage, infection, arteriovenous fistula formation, and adjacent organ injury. For complex kidney stones, neither PCNL nor ESWL alone may be sufficient, and a combination of both methods can be used complementarily.

Intraoperative and postoperative bleeding are the most common and dangerous complications of PCNL. If significant bleeding occurs during surgery, the procedure should be halted, and a nephrostomy tube should be placed for hemostasis. Postoperative bleeding often occurs after nephrostomy tube removal. In cases of severe bleeding, interventional vascular embolization is required immediately. If hemostasis proves unsuccessful, nephrectomy may become necessary to save the patient’s life.

Ureteroscopic Lithotripsy (URL)

URL involves the insertion of a ureteroscope through the urethra to locate the ureteral orifice within the bladder. Under guidance from a safety wire, the scope is advanced into the ureter, where energy sources are used to fragment the stone, and tools retrieve the fragments. URL is indicated for middle and lower ureteral stones, upper ureteral stones unresponsive to ESWL, radiolucent ureteral stones, long-standing impacted stones, and "stone street" formation caused by ESWL.

URL is unsuitable for cases of severe ureteral stenosis or twisting, uncontrolled urinary tract infection, or systemic bleeding disorders. Large or tightly impacted stones also pose challenges for the procedure. Complications include infection, submucosal ureteral injury, false passage formation, perforation, and tearing. Severe complications such as ureteral avulsion or transection during surgery are associated with high-pressure irrigation or improper manipulation. Immediate conversion to open surgery is necessary if these complications occur.

Infectious shock is another serious complication and is closely related to preoperative assessment of infection status and preventive measures. For patients with abnormal infection markers prior to surgery, aggressive infection control or ureteral stent placement can reduce the risk of intraoperative or postoperative infection-related complications. Long-term complications primarily include ureteral stricture or obstruction.

Flexible ureteroscopy is mainly used for kidney stones smaller than 2 cm. Using a retrograde approach, a flexible ureteroscope sheath is placed under the guidance of a safety wire. The flexible ureteroscope is then advanced into the renal pelvis or calyces to locate the stone. Laser lithotripsy is used to fragment the stone into small, easily excretable pieces. Larger fragments may be removed with a stone basket.

Laparoscopic Ureterolithotomy (LUL)

This procedure is indicated for ureteral stones larger than 2 cm or for cases where ESWL and ureteroscopy have failed. It is generally not considered a first-line treatment. Surgical approaches include transabdominal and retroperitoneal, with the latter being suitable only for upper ureteral stones.

Open Surgical Treatment

With the widespread use of ESWL and endoscopic techniques, open surgery is now rarely required for the treatment of upper urinary tract stones. Available surgical techniques primarily include:

Pyelolithotomy

This procedure is mainly performed for stones located in the renal pelvis, particularly in cases of obstruction at the ureteropelvic junction. It allows for both stone removal and relief of the obstruction.

Nephrolithotomy

Depending on the location of the stone, the kidney is incised along the Brodel's line or a radial incision is made on the posterior aspect of the kidney. This method is now seldom used.

Partial Nephrectomy

This technique is applied when the stone is located in one pole of the kidney, and there is significant calyceal dilation, parenchymal atrophy, or a strong likelihood of recurrence.

Nephrectomy

Nephrectomy is used when kidney structure is severely damaged, functionality is lost due to stones, or in cases of pyonephrosis, provided the contralateral kidney is functioning well.

Ureterolithotomy

This procedure is indicated for long-standing impacted stones or stones that failed other treatment methods. The surgical approach is selected based on the location of the stone.

Approximately 15% of patients present with bilateral upper urinary tract stones. The principles of surgical treatment for such cases include:

For bilateral ureteral stones, efforts are made to simultaneously relieve the obstruction. Bilateral ureteroscopic lithotripsy can be performed, and if unsuccessful, ureteral retrograde stenting or percutaneous nephrostomy may be carried out. If conditions permit, percutaneous nephrolithotomy can also be considered.

For unilateral kidney stones accompanied by stones on the contralateral ureter, the ureteral stones should be addressed first.

For bilateral kidney stones, treatment priorities are determined by safety and feasibility. The kidney with easily removable stones is treated first, with efforts to preserve as much kidney tissue as possible. In cases of extremely poor renal function, severe obstruction, or poor general health, percutaneous nephrostomy is preferred as the initial step. Subsequent stone treatment is performed after the patient's condition improves.

For solitary kidney stones or bilateral upper urinary tract stones causing acute complete urinary obstruction and anuria, timely surgical intervention is necessary once the diagnosis is confirmed, provided the patient's overall condition allows for surgery. When surgery is not feasible due to severe systemic illness, ureteral stenting can be attempted to achieve drainage through the stone, or percutaneous nephrostomy can be performed if stenting is unsuccessful. The goal of these interventions is to drain urine and improve renal function. Further appropriate treatment is planned after the patient's condition stabilizes.

Prevention

Urinary stone formation involves various factors and is associated with a high recurrence rate. Approximately one-third of patients with kidney stones experience recurrence within five years of treatment. Therefore, appropriate preventive measures are of great significance.

Increased Fluid Intake

Maintaining a high fluid intake increases urine output, dilutes the concentration of stone-forming substances in the urine, and reduces crystal deposition. Increased hydration also facilitates the passage of stones. Drinking water at least once during the night helps maintain diluted urine overnight, thereby reducing crystal formation. A daily urine output exceeding 2,000 ml is an essential preventive measure for all types of stone-forming conditions in adults.

Dietary Adjustments

Maintaining a balanced nutritional diet and avoiding excessive intake of specific components is emphasized. Diet composition should be adjusted based on stone type and metabolic status. For patients with absorptive hypercalciuria, a low-calcium diet is recommended; however, calcium restriction is generally not advised for other types of calcium stones. Patients with calcium oxalate stones should limit foods such as strong tea, spinach, tomatoes, asparagus, and peanuts. Patients with hyperuricemia should avoid purine-rich foods, such as animal organs. Urinary pH should be monitored regularly, with the goal of maintaining a pH above 6.5 to prevent uric acid and cystine stones. Additionally, excessive intake of sodium and protein should be limited, while increasing the consumption of fiber-rich foods such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains is encouraged.

Specific Prevention

After a detailed metabolic evaluation, specific preventive measures can be taken:

Patients with calcium oxalate stones may benefit from the oral administration of vitamin B6 to reduce oxalate excretion.

Patients with uric acid stones may take allopurinol and sodium bicarbonate to inhibit stone formation.

For conditions such as urinary obstruction, foreign bodies in the urinary tract, urinary tract infections, or prolonged immobility, it is critical to address these underlying risk factors for stone formation promptly.