Echinococcosis of the liver, also known as hydatid disease of the liver, is a zoonotic parasitic disease caused by the larval stage (metacestode) of Echinococcus tapeworms.

Etiology and Pathology

Four species of Echinococcus tapeworms are recognized as pathogenic: Echinococcus granulosus, Echinococcus multilocularis (or alveolar hydatid), Echinococcus vogeli, and Echinococcus oligarthrus. Among these, Echinococcus granulosus is the most common species and predominantly affects pastoral regions and semi-pastoral areas in western regions. Sporadic cases are reported in other regions as well. In high-altitude pastoral areas, the prevalence of alveolar echinococcosis (E. multilocularis) is also relatively high.

The definitive hosts of Echinococcus granulosus include dogs, foxes, and wolves, with dogs being the most common. Intermediate hosts are sheep, pigs, horses, cattle, and occasionally humans, with sheep being the most frequent host. Clinically, hepatic echinococcosis is the most common form, accounting for approximately 75% of cases, followed by pulmonary echinococcosis at about 15%.

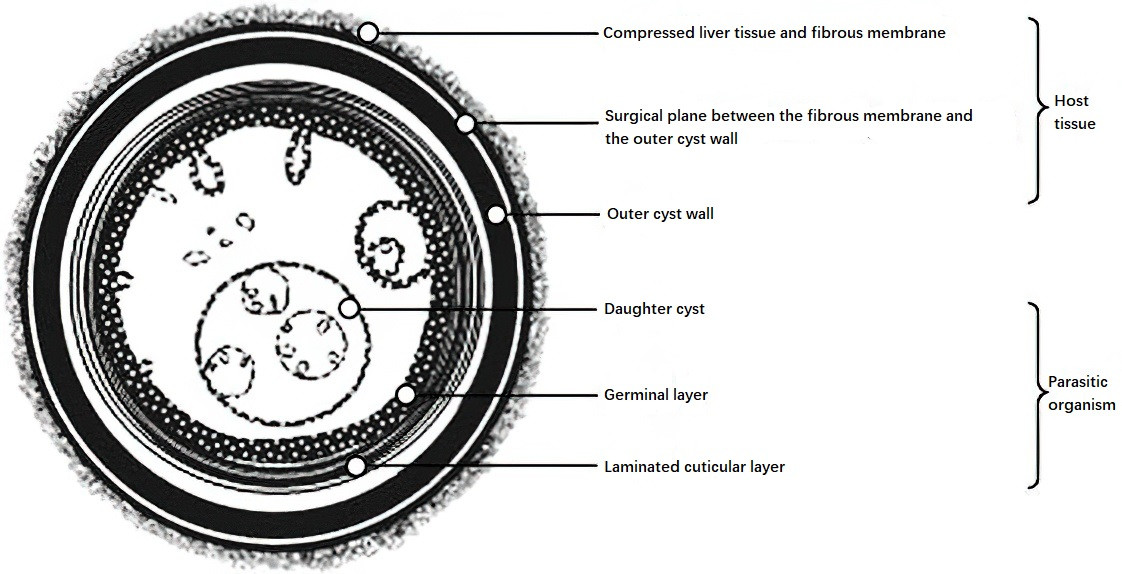

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of hepatic hydatid cyst anatomy

When the hexacanth larvae enter the human body, they first develop into small cystic structures in the liver, gradually enlarging and compressing the liver parenchyma. This process forms a hydatid cyst with multilayered wall structures and a variety of internal contents.

The cyst wall consists of two layers:

Inner Layer (Endocyst)

This is part of the parasite and appears as a whitish, powdery layer. It is composed of two sublayers: the germinal layer and the laminated cuticular layer. The laminated layer, located outside the germinal layer, protects the germinal cells, supports them, and facilitates nutrient absorption. The germinal layer contains a row of proliferative cells capable of producing brood capsules, scoleces, and daughter cysts.

Outer Layer (Ectocyst)

This fibrous layer is formed by the host's immune response to the parasite, characterized by granulomatous inflammation with macrophages and fibrosis.

As the cyst expands, surrounding liver parenchyma undergoes compression, leading to hepatocyte degeneration, atrophy, and disappearance, accompanied by fibrosis. This creates a fibrous membrane-like structure between the ectocyst and adjacent hepatic tissue. A potential space exists between this membrane and the ectocyst, allowing for separation of the cyst from the liver parenchyma along this plane.

After entry into the human body, the hydatid cyst undergoes progressive stages of colonization, growth, and eventual degeneration, reflecting the interaction between the parasite and the host. Most cysts grow slowly, showing a range of pathological changes depending on the stage. Cyst sizes vary, and their internal structure may present as single chambers, multi-daughter cysts, collapsed endocysts, or necrotic tissue. Over time, the cyst fluid can change from clear to turbid, shrink as water is absorbed, and develop caseous material or calcifications. The ectocyst may thicken and calcify, and some cysts rupture into the biliary tract, abdominal cavity, or thoracic cavity, forming fistulas.

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

Hydatid cysts grow slowly and are asymptomatic in the absence of complications. They are often incidentally discovered during routine physical examinations. Some patients present with abdominal masses, compression symptoms caused by the cyst, or complications. Clinical features vary depending on the parasite’s location, cyst size and number, host reactivity, and complications such as rupture, compression, or infection.

Cyst Rupture

If cyst contents spill into the abdominal cavity, this can lead to severe allergic reactions. Scoleces implanted into the abdominal cavity may produce multiple secondary cysts, resulting in abdominal distension or intestinal obstruction.

Cyst rupture into the biliary tract can cause obstructive jaundice or recurrent cholangitis.

Rupture through the diaphragm into the thoracic cavity, including the lungs, may result in recurrent pulmonary infections.

Cyst Compression

Compression of the bile ducts may cause jaundice.

Compression of the hepatic veins can lead to Budd-Chiari syndrome (refer to "Portal Hypertension").

Infection

Secondary bacterial infection is relatively common and often linked to biliary fistulas. Symptoms resemble bacterial liver abscesses, with pronounced systemic and local symptoms.

Allergic Reactions

Cyst rupture can trigger urticaria or, in severe cases, anaphylactic shock.

Hydatid disease can affect nearly every organ in the body.

Diagnosis

Most patients have a history of living in endemic areas or contact with dogs, sheep, or other known hosts. Diagnostic methods include:

Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasound has a high diagnostic accuracy and is the preferred method, often used for epidemiological screening. It helps to determine the developmental stage and classification of hydatid cysts. Ultrasound findings for hydatid cysts include cystic lesions (CL), unilocular cysts (type I), multi-daughter cysts (type II), collapsed endocysts (type III), solid degeneration (type IV), and calcified cysts (type V). Biliary dilatation may be observed if the cyst ruptures into the biliary tract.

CT and MRI

These techniques provide characteristic imaging features and detailed information about the relationship between the cyst and adjacent structures.

Immunological Tests

The Casoni skin test yields a positive rate of approximately 90–95%.

The complement fixation test has a positive rate of 70–90%. These results provide supportive evidence for diagnosis.

Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is primarily used for cases of pediatric echinococcosis, large cysts, or cysts with complications. The general surgical principles involve removing the outer cyst (either completely or partially) and the inner cyst, preventing spillage of cystic contents to avoid recurrence, and appropriately managing residual cavities and biliary fistulas to reduce postoperative complications.

Complete or Partial Excision of the Outer Cyst Wall

The outer cyst can be completely excised along the potential plane between the fibrous membrane and the surrounding tissue. When complete excision is challenging, the inner cyst is first removed, followed by subtotal or partial resection of the outer cyst. This method effectively addresses postoperative recurrence and residual cavity-related complications, making it the preferred approach for radical surgery.

During the procedure, biliary ducts leading to the cyst cavity must be carefully ligated. For partial excision of the outer cyst, all small openings of bile ducts on the residual cyst wall should be securely sutured. Larger biliary fistulas at the hepatic hilum can be addressed with a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. If contents have spilled into the biliary tract, common bile duct exploration is performed to thoroughly clear them.

Inner Cyst Removal

This classic surgical method requires preventing leakage of the cyst fluid and ensuring inactivation of protoscoleces. A closed-aspiration approach removes as much cyst fluid as possible, followed by instillation of 20% sodium chloride solution into the cyst. After being left for five minutes, the solution is aspirated, and the process is repeated 2–3 times to inactivate the protoscoleces. The outer cyst wall is incised, and the inner cyst is removed. Any protruding portions of the outer cyst are excised. Necrotic tissue within the residual cavity is cleaned, and leakage from small bile ducts is carefully sutured. The residual cavity can be packed with omentum and connected to negative pressure drainage to promote healing.

Liver Resection

This approach is applicable to localized single or multiple cysts, or when residual cavities cannot be closed after drainage of the cyst.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological treatment rarely achieves complete cure. It is suitable for patients with early-stage, small cysts with thin outer walls, cases of widespread dissemination, or during the perioperative period. Albendazole is the frequently used medication, typically administered orally for at least six months starting one week before surgery. Some patients respond effectively to this treatment.

Percutaneous Aspiration Therapy Under Ultrasound Guidance

In this procedure, a needle or catheter is introduced into the cyst under ultrasound guidance to aspirate its fluid. Afterward, 20% sodium chloride solution is injected, retained for 10–15 minutes, and then aspirated. This method is suitable for small type I cysts located within the liver parenchyma and can be repeated as necessary to eliminate the parasite. However, this technique is not suitable for cases where the cyst communicates with the bile ducts.

In addition, patients with cysts smaller than 5 cm in diameter that have solidified or calcified (type IV or V) and are asymptomatic can be monitored through regular follow-up.

Alveolar echinococcosis of the liver, caused by Echinococcus multilocularis larvae, is more common in endemic high-altitude regions where foxes serve as the primary definitive host. The larvae exhibit small, vesicular, expansile growth, causing hepatocyte necrosis and granulomatous inflammation. The parasite grows irregularly within the liver and frequently compresses the bile ducts, hepatic veins, inferior vena cava, and diaphragm. Early surgical resection of the lesions offers the potential for cure, while patients with extensive lesions who are inoperable have a poorer prognosis. Albendazole is effective for treatment but does not provide a definitive cure.