Rectal prolapse refers to the downward displacement of part or the entire wall of the rectum. When only the mucosal layer of the rectum is displaced downward, it is referred to as mucosal prolapse or incomplete prolapse. When the full thickness of the rectal wall is displaced downward, it is termed complete prolapse. If the displaced rectal wall remains within the rectum or anal canal, it is called internal prolapse, whereas displacement beyond the anal opening is referred to as external rectal prolapse. Clinically, rectal prolapse typically refers to external rectal prolapse.

Etiology and Pathology

The exact causes of rectal prolapse are not yet fully understood.

Anatomical Factors

Incomplete development, malnutrition, or physical frailty in infants and young children, as well as in the elderly and debilitated adults, may lead to weakened levator ani muscles and pelvic floor fascia. Additionally, factors such as reduced sacral curvature in children, trauma, surgery, or damage to the muscles and nerves around the anorectal area can all diminish the ability of the surrounding structures to stabilize and support the rectum, predisposing it to downward displacement and prolapse.

Increased Intra-Abdominal Pressure

Conditions that elevate intra-abdominal pressure, such as constipation, diarrhea, benign prostatic hyperplasia, chronic cough, difficulty with urination, and childbirth, can push the rectum downward, leading to prolapse.

Other Factors

Severe hemorrhoids and frequently prolapsing rectal polyps can exert a downward pulling effect on the rectal mucosa, potentially causing prolapse. For mucosal prolapse, the pathological change involves loosening of the connective tissue between the mucosal and muscular layers in the lower rectum, allowing the mucosa to displace downward. Complete prolapse, on the other hand, involves relaxation of the connective tissues supporting the rectum, resulting in downward displacement of the entire rectal wall. In prolapse cases, the exposed rectal mucosa may develop inflammation, erosion, ulcers, bleeding, or even become incarcerated and necrotic. Persistent stretching and passive relaxation of the anal sphincter can cause anal incontinence, which in turn exacerbates the progression of prolapse.

In infants and young children, rectal prolapse is often associated with growth, development, and nutritional status, and spontaneous resolution is common by around the age of five. In adults, however, unless the underlying causes are addressed, spontaneous resolution is rare, and the condition tends to progressively worsen.

Clinical Manifestations

The primary symptom is rectal tissue prolapsing through the anus. In the early stages, the amount of tissue prolapsed is small and occurs during defecation, returning to its original position spontaneously afterward. As the condition progresses, the prolapsed mass becomes larger and more frequently displaces, eventually requiring manual repositioning into the anus after defecation. Patients may experience a sensation of incomplete evacuation and pelvic heaviness. Advanced cases may involve prolapse occurring during coughing, straining, or even standing.

As the prolapse worsens, varying degrees of anal incontinence may develop, often accompanied by mucus discharge, leading to perianal eczema and pruritus. Difficulty in rectal evacuation can result in constipation. Erosion and ulceration of the mucosa may lead to bleeding. Internal prolapse often lacks obvious symptoms but may present as a feeling of incomplete evacuation or difficulty during defecation. Occasionally, internal prolapse is discovered incidentally during barium enema X-ray examination.

Physical Examination

During physical examination, patients may be asked to squat and perform a straining maneuver to simulate defecation, causing rectal prolapse to become visible. Partial prolapse appears as a smooth, circular, pink, protruding mass with irregularly circular mucosal folds. In cases of internal mucosal prolapse, digital rectal examination may reveal that the rectum feels filled with mucosa, lacking the normal hollow sensation.

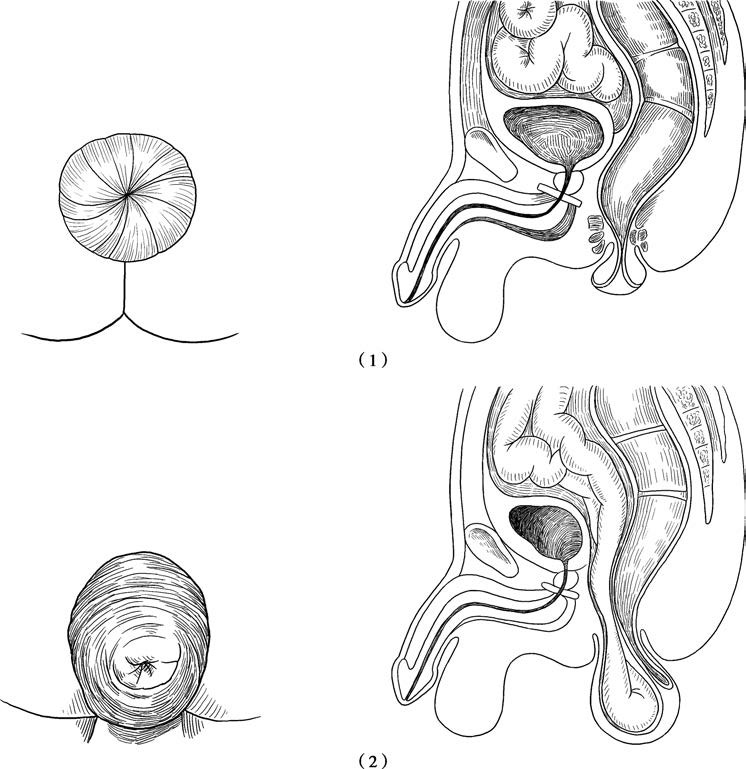

Figure 1 Types of rectal prolapse

(1) Rectal mucosal prolapse

(2) Complete rectal prolapse

In digital examination for rectal prolapse, the anal opening may appear widened, and the anal sphincter may be weak or markedly diminished in tone. When patients are instructed to contract their sphincter, only mild contraction may be observed. Complete rectal prolapse is characterized by concentric rings of mucosal folds on the surface of the prolapsed tissue. A significant prolapse may involve folding of two layers of the rectal wall, resulting in a thicker protrusion, particularly on the mesorectal side.

In rare cases, abdominal contents (e.g., small intestine) may herniate into the lowered peritoneal recess of the prolapsed rectum, forming an asymmetrical mass. When the anal canal itself does not prolapse, a deep groove may form between the anus and the prolapsed bowel. Defecography may reveal telescoping of the proximal bowel segment into the distal rectum.

Treatment

In infants and young children, non-surgical treatment is typically prioritized for rectal prolapse, while mucosal prolapse in adults may be managed with sclerosing agent injection therapy or mucosal resection. Complete rectal prolapse in adults is generally treated surgically, with efforts made to address underlying factors contributing to prolapse.

General Treatment

Rectal prolapse in infants and young children has the potential for spontaneous resolution. Non-surgical treatment primarily focuses on improving nutrition and enhancing pelvic floor function through exercises. Underlying conditions that lead to elevated intra-abdominal pressure, such as constipation and coughing, should be addressed. Prolapsed rectal tissue can be repositioned immediately after defecation to prevent further complications such as incarceration or worsening of the condition.

Injection Therapy

Injection therapy involves administering sclerosing agents into the submucosal layer of the prolapsed tissue, inducing aseptic inflammation to promote adhesion and fixation between the mucosal and muscular layers. This approach is mainly used for internal mucosal prolapse and employs the same sclerosing agents used for hemorrhoid injection treatments. Short-term outcomes after injections are generally satisfactory.

Surgical Treatment

Complete rectal prolapse in adults is primarily managed with surgical procedures, which vary and have distinct advantages and limitations. Surgical approaches include abdominal, perineal, abdominoperineal, and sacral routes, with the first two being more commonly employed.

Rectopexy

Rectopexy is considered a reliable method for treating rectal prolapse. The use of laparoscopic or robot-assisted techniques has improved the effectiveness of rectopexy while reducing surgical trauma and complications. During the procedure, the rectum is mobilized and then suspended and fixed to surrounding structures, such as the presacral fascia, sacral promontory, or lateral pelvic tissues. Care is taken to avoid damage to nearby nerves and the presacral venous plexus. The pelvic floor fascia and levator ani muscles may also be sutured to address any associated laxity. Additionally, the use of biological mesh materials in recent years has provided enhanced support for pelvic floor tissues. For patients with coexisting constipation, redundant portions of the sigmoid colon may be resected.

Anorectal Stapled Mucosal Resection

For mucosal prolapse, excessive prolapsed mucosa can be removed using stapling techniques through the anus. Elderly or physically frail patients may undergo simpler procedures, such as anal ring constriction or sigmoid colostomy.

Perineal Approach

The perineal approach is considered relatively safe. Classical procedures include the Delorme and Altemeier surgeries. The Delorme procedure involves removing redundant mucosa while preserving and folding the muscular layer of the rectum, followed by mucosal anastomosis. The Altemeier procedure allows for the direct removal and anastomosis of the prolapsed rectum—and sometimes the sigmoid colon—through the anus. For cases with widened gaps in the levator ani muscles, repair and reconstruction of the muscle can be performed.