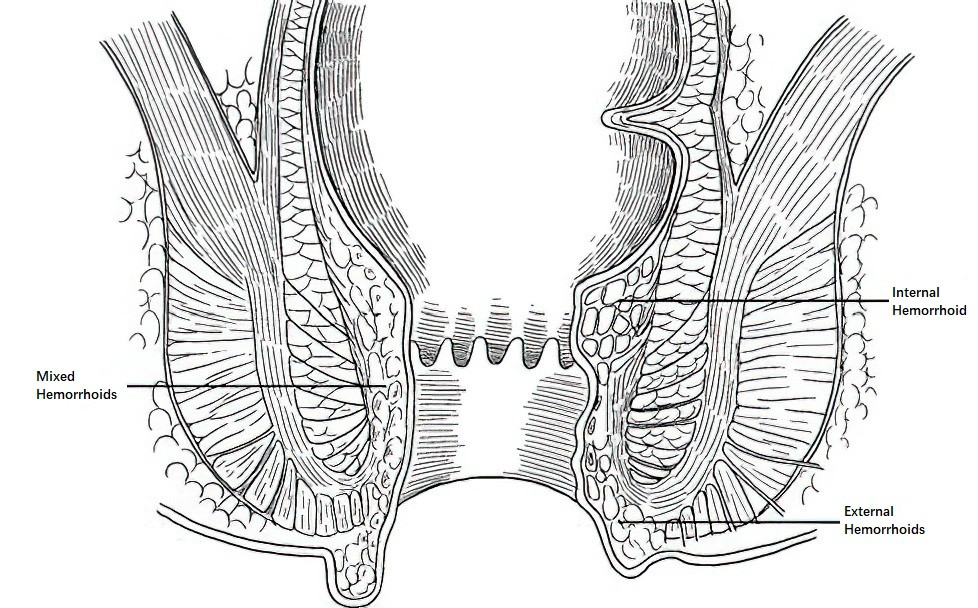

Hemorrhoids are the most common anorectal disorder. While hemorrhoids are rare in infants and young children, the incidence increases with age. Internal hemorrhoids are pathological changes in the supporting structures of the anal cushions, venous plexus, and arteriovenous anastomoses, leading to congestion, hyperplasia, hypertrophy, and displacement of the anal cushions. External hemorrhoids result from pathological dilation of the subcutaneous venous plexus or connective tissue hyperplasia distal to the dentate line. Internal hemorrhoids and external hemorrhoids can merge through rich venous plexus anastomoses at corresponding sites, forming mixed hemorrhoids.

Etiology

The exact cause of hemorrhoids remains unclear, but current theories include:

Anal Cushion Displacement Theory

Beneath the anal canal mucosa lies a vascular cushion composed of blood vessels, smooth muscles, and connective tissue, collectively referred to as the anal cushion. This structure plays a role in sealing the anal canal and controlling defecation. Under normal circumstances, the anal cushion is anchored to the anal canal's muscular wall by the Treitz muscle and some fibrous tissue. During defecation, downward pressure moves it downward; afterward, the cushion retracts into the anal canal through its elastic recoil. When this recoil weakens, the anal cushion becomes congested, displaced, and hypertrophic, leading to hemorrhoid formation.

Varicose Vein Theory

This theory suggests that hemorrhoid formation is related to venous dilation and blood stasis. Anatomically, the portal venous system and its branches lack valves, while the walls of the rectal venous plexus are thin and located at shallow positions at the lowest points of the abdominal and pelvic cavities. Additionally, the submucosal tissue of the distal rectum is lax. These factors predispose to blood stasis and venous dilation. Since the venous plexus is a primary structure of the anal cushions, pathological dilation and blood stasis within it are directly linked to hemorrhoid formation. Many factors can obstruct rectal venous return because of the rectum's location in the lowest part of the abdominal cavity. Such factors include prolonged sitting or standing, constipation, diarrhea, pregnancy, prostatic hyperplasia, or large pelvic tumors.

Additionally, long-term alcohol consumption and excessive intake of irritant foods can lead to local congestion. Perianal infection can result in perivenous inflammation, causing the veins to lose elasticity and dilate. Malnutrition can weaken and atrophy local tissues. These factors collectively increase the likelihood of hemorrhoid development.

Classification and Clinical Manifestations

Hemorrhoids are classified into three types based on their location:

Figure 1 Classification of hemorrhoids

Internal Hemorrhoids

The main clinical manifestations of internal hemorrhoids are bleeding and prolapse. Intermittent rectal bleeding during defecation is the most common symptom. In the absence of thrombosis, incarceration, or infection, internal hemorrhoids are generally painless but may occasionally be accompanied by difficulty passing stools. Internal hemorrhoids commonly occur at the 3 o’clock, 7 o’clock, and 11 o’clock positions in the lithotomy position. The grading of internal hemorrhoids is as follows:

- Grade I: Bleeding or blood-streaked stools without prolapse. Bleeding stops spontaneously after defecation.

- Grade II: Hemorrhoids prolapse during defecation but spontaneously retract afterward. Bleeding may occur.

- Grade III: Hemorrhoids prolapse beyond the anus during defecation, prolonged standing, coughing, physical exertion, or heavy lifting, requiring manual reduction. Bleeding may occur.

- Grade IV: Hemorrhoids are irreducible or prolapse again after reduction. Bleeding may occur.

External Hemorrhoids

The main clinical features include anal margin skin tags or small masses, perianal discomfort, moisture, and occasionally pruritus. Acute thrombosis can lead to severe anal pain, termed thrombosed external hemorrhoids.

Mixed Hemorrhoids

Symptoms of both internal and external hemorrhoids may coexist. Internal hemorrhoids that progress to Grade III or higher often form mixed hemorrhoids. As mixed hemorrhoids worsen, they can prolapse circumferentially beyond the anus, forming ring-shaped hemorrhoids, which manifest as petal-like or annular prolapsed masses around the anus. If the prolapsed masses become incarcerated by the spasmodic sphincter, they may develop edema, congestion, or even necrosis, termed incarcerated or strangulated hemorrhoids in clinical practice.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Through direct visual inspection of the anus, the size, number, location, and mucosal erosion of hemorrhoids can be observed, especially in cases of prolapse, ideally evaluated after squatting during defecation. Digital rectal examination assesses for other potential rectal disorders such as rectal cancer, rectal polyps, or hypertrophic anal papillae. Anoscopy allows for examination of hemorrhoid mucosa and detection of rectal mucosal changes such as congestion, edema, or ulceration. Thrombosed external hemorrhoids appear as dark purplish oval masses around the anus, characterized by firm consistency, tenderness, and significant pain on palpation.

While hemorrhoid diagnosis is generally straightforward, differentiation from the following conditions is necessary:

Rectal Cancer

Rectal cancer is sometimes misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids, leading to delayed treatment. This often occurs when diagnosis is based solely on symptoms without a digital rectal or colonoscopic examination. Rectal cancer may present as an irregular, firm mass palpable on digital rectal examination, often with dark red blood on the examining glove.

Rectal Polyps

Low-positioned pedunculated polyps that prolapse beyond the anus can be misdiagnosed as prolapsed hemorrhoids. Such polyps are typically round, solid, mobile, and pedunculated, commonly detected in children.

Hypertrophic Anal Papillae

Pedunculated masses originating from the dentate line region are often hypertrophic anal papillae.

Rectal Prolapse

Rectal prolapse involves concentric mucosal folds, often accompanied by sphincter laxity.

Treatment

The primary principles of treatment for hemorrhoids include the following:

- Asymptomatic hemorrhoids require no intervention.

- The focus of treatment is on alleviating or eliminating symptoms rather than pursuing complete eradication.

- Non-surgical methods are the mainstay of treatment.

General Treatment

In the early stages of hemorrhoids and for asymptomatic cases, increasing dietary fiber intake, correcting poor bowel habits, and maintaining smooth bowel movements to prevent constipation and diarrhea are important. Warm sitz baths can improve local blood circulation. In cases of thrombosed external hemorrhoids, symptoms may resolve without surgery after localized application of warm compresses and anti-inflammatory, pain-relieving ointments. In the early stages of incarcerated hemorrhoids, conservative measures can include manual reduction of prolapsed hemorrhoidal tissue back into the anal canal, followed by placement of a gauze pad to prevent recurrence of prolapse.

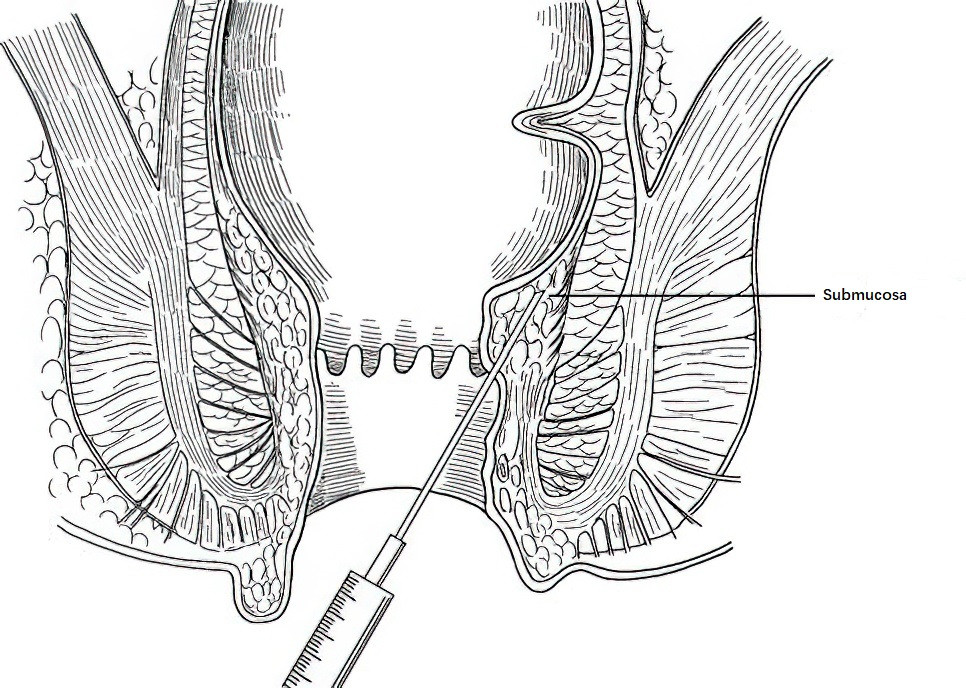

Injection Therapy

Injection therapy is effective for treating Grade I and II bleeding internal hemorrhoids. The aim of injecting sclerosing agents is to induce an aseptic inflammatory reaction around the hemorrhoid and its surrounding tissue, causing submucosal fibrosis and subsequent hemorrhoid shrinkage. Commonly used sclerosing agents include 5% phenol in vegetable oil, and 5% sodium morrhuate. Corrosive substances should not be used.

Figure 2 Injection therapy for internal hemorrhoids

The standard procedure involves local perianal anesthesia to relax the anal sphincter. After inserting a speculum to visualize the hemorrhoid, the sclerosing agent is injected submucosally into the area above the hemorrhoid at 2 to 3 ml per injection. Sites for injection typically include the left rectal wall, right anterior, and right posterior regions near the dentate line. Gentle massage of the injection site follows to distribute the agent evenly. Care is taken to avoid injecting the mucosal layer alone to prevent mucosal necrosis. If results are suboptimal after the first session, a repeat injection can be performed after one month. If multiple hemorrhoids are present, the procedure may be divided into 2 to 3 sessions.

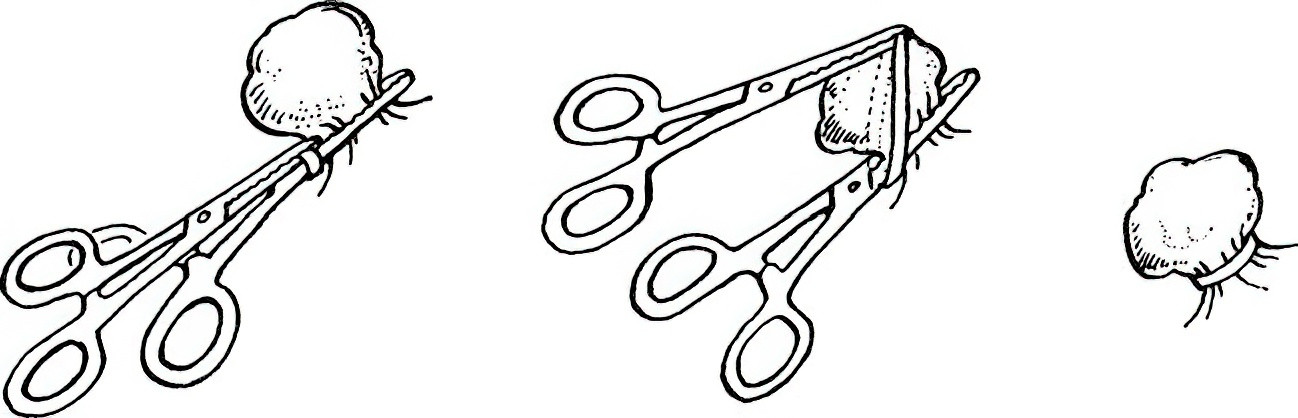

Rubber Band Ligation Therapy

This method is suitable for treating Grades I, II, and III internal hemorrhoids. The principle of the therapy is to place a specially designed rubber band at the base of the internal hemorrhoid to block its blood supply, leading to chronic ischemia, necrosis, detachment, and eventual healing. There are two main types of rubber band ligators: traction ligators and suction ligators. If specialized instruments are unavailable, two hemostatic forceps can be used as substitutes. Post-procedure care focuses on managing defecation to prevent hard stools, as bleeding may occur when the hemorrhoid detaches. Rubber bands should not be placed at or below the dentate line or on skin, as this may lead to severe pain.

Figure 3 Rubber band ligation therapy for internal hemorrhoids

Doppler-Guided Hemorrhoidal Artery Ligation (HAL)

This procedure, suitable for Grade II to IV internal hemorrhoids, employs a specially designed rectoscope equipped with a Doppler ultrasound probe. The probe detects hemorrhoidal arteries located 2 to 3 cm above the dentate line, which are then precisely ligated to interrupt the hemorrhoid’s blood supply and alleviate symptoms.

Surgical Treatment

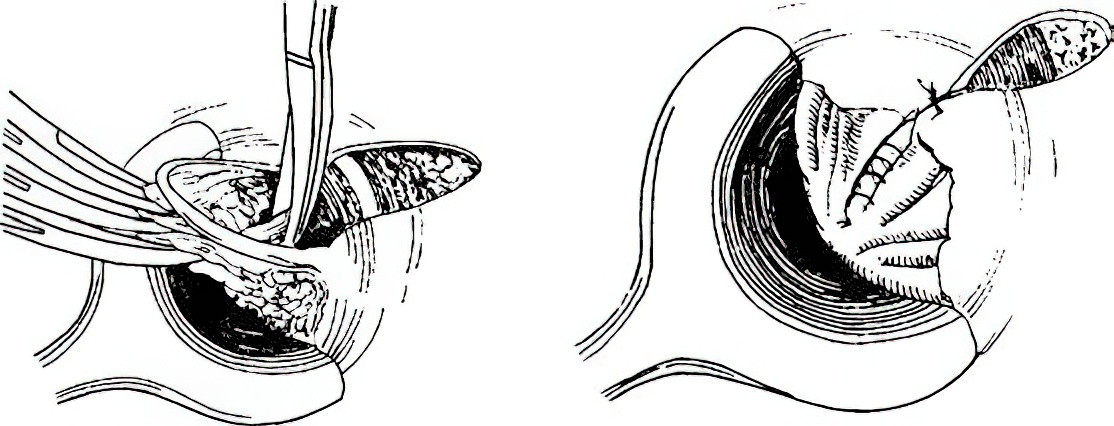

Hemorrhoidectomy

Hemorrhoidectomy is primarily used for treating Grade II to IV internal hemorrhoids and mixed hemorrhoids. The patient is positioned in the lateral, lithotomy, or prone position. Following anesthesia and adequate anal sphincter relaxation, controlled dilation of the anus is performed to expose the hemorrhoidal tissue. V-shaped incisions are made on the skin at the base of the hemorrhoid on either side of the anal margin. The varicose vein mass is carefully separated until the internal anal sphincter is exposed. Hemorrhoidal tissue at the base is clamped with hemostatic forceps, ligated, and excised distal to the ligation point. Mucosal layers above the dentate line are sutured with absorbable stitches, while skin incisions below the dentate line may be left unsutured. Incarcerated hemorrhoids can also be managed using this method.

Figure 4 Hemorrhoidectomy

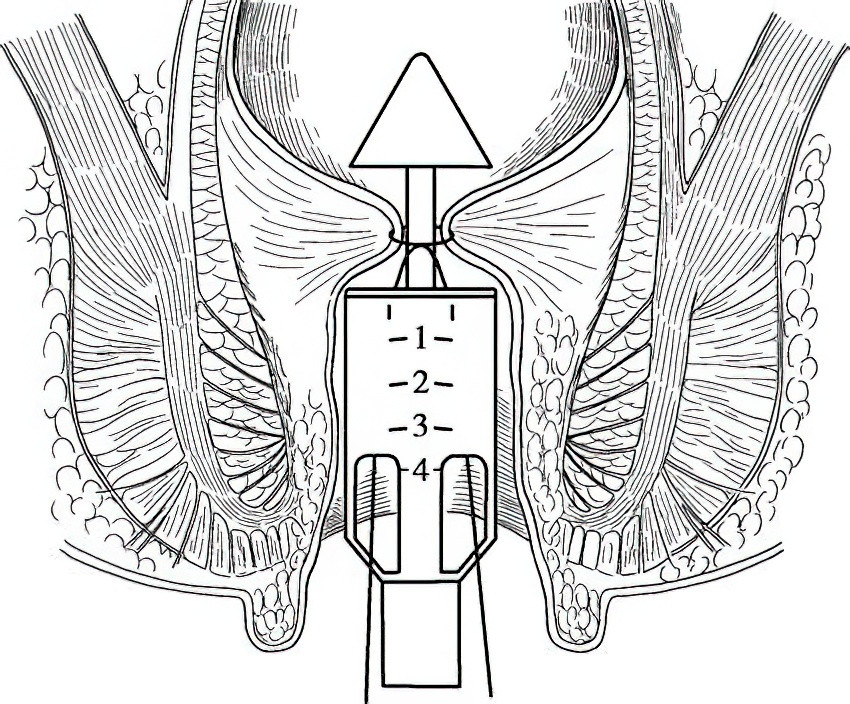

Stapled Hemorrhoidopexy (PPH)

This technique is used for Grade III and IV internal hemorrhoids, recurrent Grade II hemorrhoids after failed non-surgical treatment, annular hemorrhoids, and rectal mucosal prolapse. A specially designed tubular circular stapler is used to excise a circumferential strip of rectal mucosa and submucosa located 2 to 4 cm above the dentate line. This procedure repositions and secures displaced anal cushions. Known as the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH), it offers advantages over conventional hemorrhoidectomy, including less pain, shorter operative time, and faster recovery.

Figure 5 Stapled hemorrhoidopexy (PPH)

Tissue-Selecting Therapy (TST)

TST is suitable for Grade III and IV internal hemorrhoids. The underlying principle is similar to that of PPH. Using a specially designed anoscope, selective removal of rectal mucosa and submucosa located 2 to 4 cm above the dentate line is performed with a stapler. This procedure allows for tailored excision while effectively preserving healthy rectal wall and anterior rectal tissue, minimizing the risk of postoperative complications such as rectal stenosis or rectovaginal fistula. It has a smaller impact on postoperative rectal function compared to other methods.

Thrombosed External Hemorrhoid Excision

This procedure is used for thrombosed external hemorrhoids. Under local anesthesia, an elliptical incision is made on the skin surface over the hemorrhoid to remove the thrombosed tissue. The wound is left open without sutures.

Numerous methods exist for managing hemorrhoids. Injection therapy and rubber band ligation are effective for most hemorrhoids and are therefore considered primary treatments. Surgical intervention is typically reserved for cases of severe hemorrhoids or failure of non-surgical treatments.