Anal fistula refers to a granulomatous tract around the anal canal and rectum, consisting of three parts: the internal opening, the fistulous tract, and the external opening. The internal opening is commonly located at the anal crypt and is usually singular, while the external opening is found on the perianal skin and may be single or multiple. Persistent symptoms or recurrent flare-ups are characteristic features. Anal fistula can occur at any age but is more commonly seen in young and middle-aged men. Complex anal fistula is considered one of the most challenging conditions to treat in colorectal surgery.

Etiology and Pathology

Most anal fistulas arise from perianal abscesses, where the rupture or surgical drainage of the abscess forms an external opening on the perianal skin. Due to rapid growth of tissue over the external opening, pseudo-healing often occurs, and repeated ruptures or incisions can lead to multiple fistulous tracts and external openings, resulting in a complex anal fistula. Specific inflammatory conditions such as tuberculosis, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease, as well as malignant tumors or infections following anal canal trauma, may also cause anal fistulas, although these instances are less common.

Classification

There are various methods for classifying anal fistulas, with the following two being widely used in clinical practice:

Classification Based on the Vertical Position of the Fistulous Tract

Annal fistula can be classified into:

- Low-Level Anal Fistula: The fistulous tract is located below the deep portion of the external anal sphincter. It can be further divided into:

- Simple Low-Level Anal Fistula: A single fistulous tract is present.

- Complex Low-Level Anal Fistula: Multiple tracts and external openings are observed.

- High-Level Anal Fistula: The fistulous tract is located above the deep portion of the external anal sphincter. It can be further divided into:

- Simple High-Level Anal Fistula: A single fistulous tract is present.

- Complex High-Level Anal Fistula: Multiple tracts and external openings are observed.

Classification Based on the Relationship Between the Fistulous Tract and the Anal Sphincter (Parks Classification)

Annal fistula can be classified into:

- Intersphincteric Type: Accounts for approximately 70% of all anal fistulas. The primary infection occurs between the internal and external anal sphincters. The internal opening is typically located near the dentate line in the anal crypt, while the external opening is usually near the anal verge. This subtype is commonly a low-level fistula.

- Transsphincteric Type: Makes up about 25% of cases. The fistulous tract passes through the external anal sphincter and the ischiorectal fossa, with the external opening located on the perianal skin.

- Suprasphincteric Type: This high-level anal fistula subtype is relatively uncommon, representing about 4% of cases. The tract extends upwards within the intersphincteric space, crosses above the puborectalis muscle, and then descends through the ischiorectal fossa to penetrate the perianal skin.

- Extrasphincteric Type: Rare, accounting for only about 0.5% of cases. It is often caused by pelvic rectal abscesses. The fistulous tract originates from the perineal skin, extends upwards through the ischiorectal fossa and the levator ani muscle, and ultimately connects to the rectum, forming an internal opening. This type may also have an internal opening located in the anal canal and can be associated with trauma, intestinal malignancy, or Crohn’s disease, making treatment particularly challenging.

Clinical Manifestations

The primary symptom is a persistent or intermittent discharge of a small amount of purulent or blood-stained secretion from the external opening. Larger anal fistulas may also be associated with the discharge of fecal matter and gas. The perianal skin often becomes moist, itchy, and occasionally eczematous due to irritation from the secretions. When the external opening closes, inadequate drainage of infection can lead to abscess formation, causing significant pain along with systemic infection symptoms such as fever, chills, and fatigue. These symptoms typically improve after the abscess ruptures or is surgically drained. Recurrent episodes of these symptoms are a hallmark of anal fistulas.

During examination, one or multiple external openings may be observed on the perianal skin. Upon applying pressure around the external opening, purulent or blood-stained secretions may be discharged. The number and position of external openings relative to the anal verge can provide clues about the complexity of the fistula. A larger number of external openings and those located further from the anal verge suggest a more complex condition.

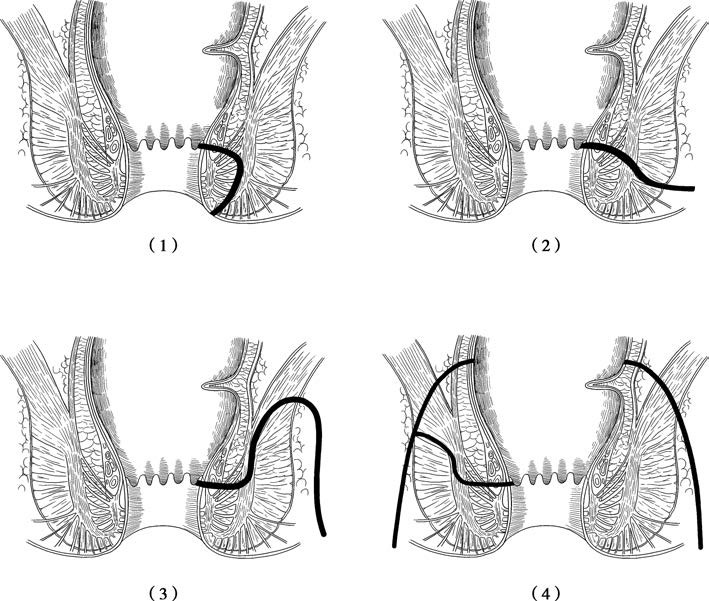

Figure 1 Four anatomical types of anal fistulas

(1) Intersphincteric type

(2) Transsphincteric type

(3) Suprasphincteric type

(4) Extrasphincteric type

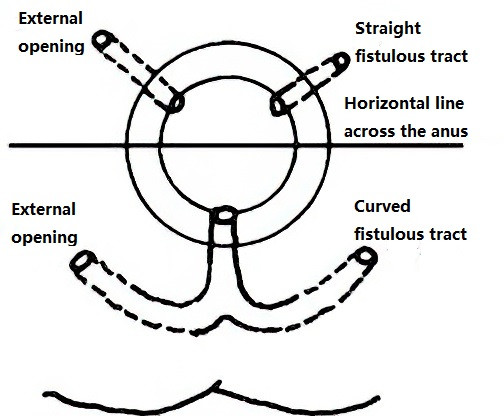

Figure 2 Goodsall’s rule

According to Goodsall’s rule, external openings located posterior to a horizontal line drawn across the midline of the anal canal typically connect to a curved fistulous tract with the internal opening situated at the posterior midline of the anal canal. Conversely, external openings located anterior to this line are usually associated with a straight fistulous tract, with the internal opening situated at the corresponding radial direction in the anal crypts. External openings close to the anal verge often indicate intersphincteric fistulas, whereas those further away are more likely to indicate transsphincteric fistulas. For lower fistulous tracts, a cord-like structure can often be palpated under the skin, extending from the external opening towards the anus.

Identifying the location of the internal opening is crucial for treatment. On digital rectal examination, mild tenderness may be felt at the site of the internal opening, and a firm, cord-like tract may be palpable. Occasionally, the internal opening can also be visualized during anoscopy. Probing the anal fistula through the external opening may risk creating a false channel, requiring the use of a soft probe.

In cases where the internal opening cannot be confirmed through conventional examination methods, injecting a small amount of methylene blue solution through the external opening and observing staining on a white gauze pad placed in the anal canal or lower rectum provides clues. MRI imaging is frequently used to clearly delineate the fistulous tract, its relationship with the sphincter, and the precise location of the internal opening. Routine preoperative MRI examination is often recommended for anal fistula patients.

For patients with complex or recurrent anal fistulas, unclear etiology, or multiple prior surgeries, barium enema X-rays or colonoscopy may help exclude the presence of conditions such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

Treatment

Anal fistulas rarely heal spontaneously, and two main treatment methods are available.

Plugging Method

After irrigating the fistulous tract with 0.5% metronidazole and saline, biological protein glue is injected through the external opening. This method is minimally invasive and painless, suitable for treating simple anal fistulas, but its cure rate is relatively low. Recently, biologically derived plugs from animal sources have also been used to fill fistulous tracts, achieving efficacy similar to that of biological protein glue.

Surgical Treatment

The principle of surgical treatment for anal fistulas involves opening or excising the fistulous tract to create an open wound, facilitating healing. Critical aspects of surgery include precisely identifying the course of the fistulous tract and the location of the internal opening, minimizing damage to the anal sphincter to prevent incontinence, and reducing the risk of recurrence.

Fistulotomy

This approach involves full-length incision of the fistulous tract to expose its lumen. Wound healing occurs by secondary intention through granulation tissue growth. Fistulotomy is suitable for low-level anal fistulas, as the tract is located below the deep portion of the external anal sphincter. This ensures that only the subcutaneous and superficial portions of the external sphincter are affected, generally avoiding severe postoperative anal incontinence.

For the procedure, the patient is positioned prone or in the lithotomy position. Methylene blue solution is first injected into the external opening to identify the position of the internal opening. A probe is inserted through the external opening, following the path of the fistulous tract. Guided by the probe, the tissue overlying the probe is incised up to the internal opening. Granulation tissue and necrotic material within the tract are curetted, and the wound edges are trimmed to ensure the wound heals outwardly from its base.

Seton Therapy

This method utilizes the mechanical pressure of a rubber band or thread with a corrosive medicinal coating to gradually sever the fistulous tract. It is suitable for low or high simple anal fistulas located within 3–5 cm of the anus, and can also be used as an adjunct to the incision or excision of complex anal fistulas. The primary advantage of seton therapy is its ability to prevent severe anal incontinence. The ligated tissue undergoes ischemia, leading to gradual necrosis and separation. Inflammatory-induced fibrosis facilitates adhesion between the severed muscle ends and surrounding tissues, minimizing muscle retraction and allowing gradual healing, thereby reducing the likelihood of significant anal incontinence.

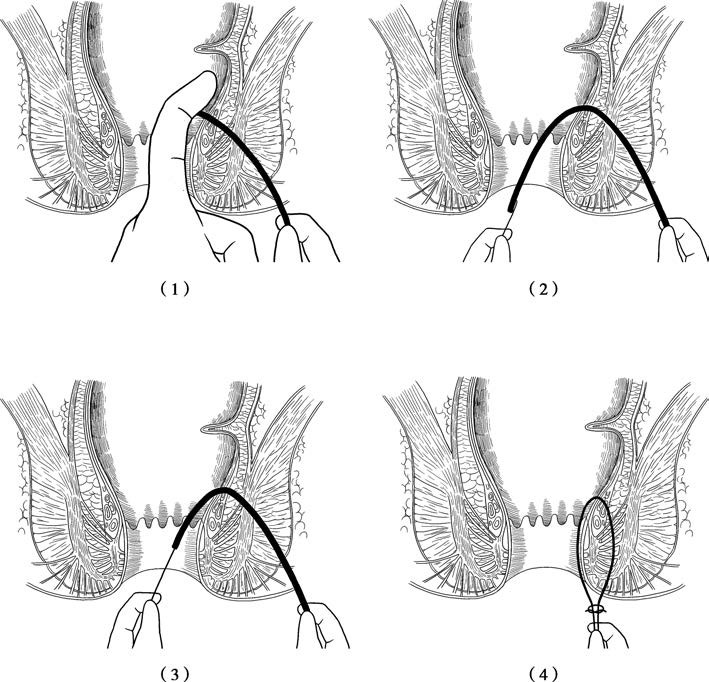

Figure 3 Seton therapy for anal fistulas

(1) A probe is inserted from the external opening toward the internal opening, with a finger placed inside the rectum or anal canal for guidance.

(2) The curved end of the probe is pulled out through the anus.

(3) A thread is secured to the end of the probe, with a rubber band attached to the thread.

(4) The probe is withdrawn to thread the rubber band through the fistulous tract. The rubber band is subsequently used for cutting or drainage seton placement, depending on the requirements of the procedure.

For the procedure, a probe is inserted through the external opening along the path of the fistulous tract until it exits at the internal opening. A sterilized rubber band or a thick silk thread is secured to the probe at the internal opening and threaded through the tract. The skin and subcutaneous tissue between the internal and external openings are then incised, and the seton is tied in place. Postoperatively, the patient undergoes regular sitz baths, particularly after bowel movements, to maintain cleanliness. If significant tissue remains under the seton for drainage, the tension of the seton may need to be tightened during follow-up. The ligated tissue typically separates and heals on its own within 10 to 14 days postoperatively.

Fistulectomy

Fistulectomy involves the excision of the fistulous tract, including its entire wall, down to healthy tissue. The resulting wound is usually left unsutured to heal by secondary intention. This method is typically reserved for simple low-level anal fistulas, or for mature, lower portions of high-level fistulas or fistulous tracts located lateral to the sphincter.

Surgical Management of Complex Anal Fistulas

Surgical treatment for complex anal fistulas requires thorough and cautious preoperative assessment of postoperative anal function and the risk of recurrence. If optimal outcomes are deemed unlikely, seton drainage and deciding to live with the fistula may be a safer option. Complex anal fistula surgeries are highly intricate, carry a high risk of recurrence, and can significantly impair anal function. For detailed management strategies, reference to specialized colorectal surgery texts is recommended.