A perianal abscess refers to an acute suppurative infection in the soft tissues or spaces surrounding the anal canal and rectum, ultimately forming an abscess. It is a general term for abscesses around the anorectal region. This condition can occur at any age, with a higher frequency in young and middle-aged adults (20–40 years), and men are more commonly affected than women. If not treated promptly or managed appropriately, the abscess may spread to deeper tissues or spontaneously rupture, forming an anal fistula. Common pathogenic bacteria include Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with occasional cases involving anaerobic bacteria or Mycobacterium tuberculosis. However, most cases involve mixed bacterial infections. The abscess represents the acute phase of perianal inflammatory processes, whereas anal fistulas are the chronic phase.

Etiology and Pathology

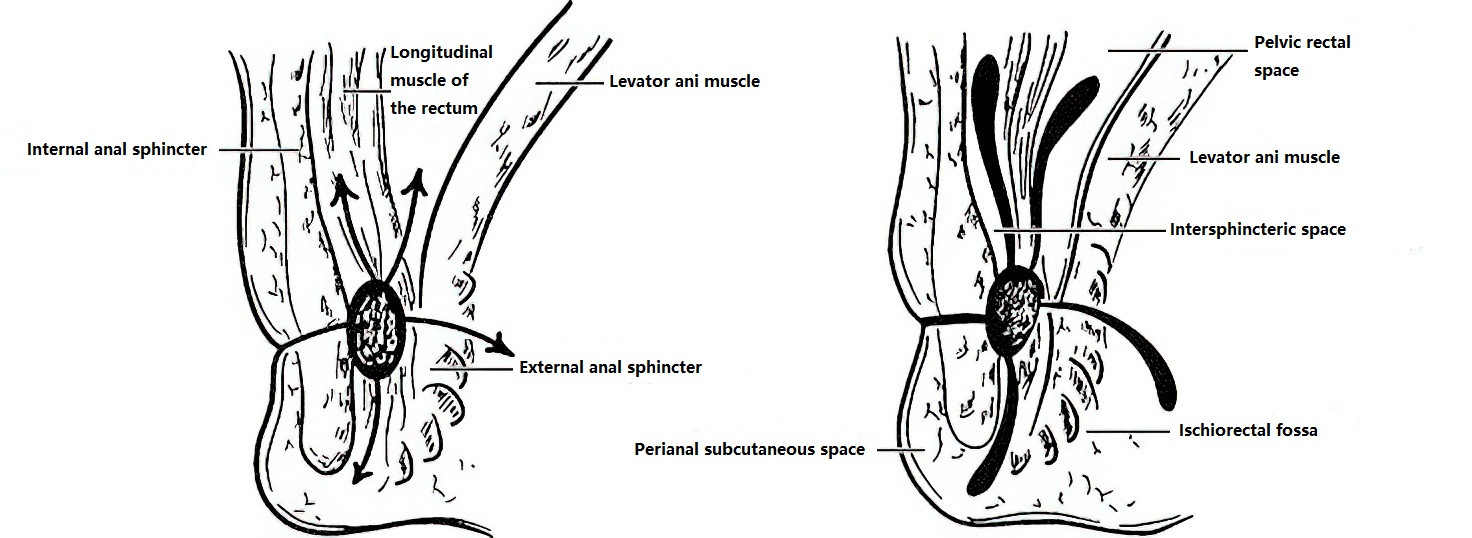

The majority of perianal abscesses are caused by infections of the anal glands. The openings of these glands are located at the anal crypts, with part of the glands situated between the internal and external sphincters. Due to the upward-facing, pouch-like structure of the anal crypts, fecal debris can easily become trapped, leading to anal cryptitis and subsequent glandular infection. Infection of the glands located between the sphincters can result in intersphincteric infections, which may progress into purulent infections of the surrounding spaces of the anorectal region, forming abscesses.

Figure 1 Pathways of infection in the perianal and rectal spaces

When the infection spreads to the loose connective tissues and fat surrounding the anorectal region, different types of perianal abscesses may form:

- Upward spread can lead to high intersphincteric abscesses or pelvic rectal abscesses.

- Downward spread can result in subcutaneous perianal abscesses.

- Lateral spread beyond the external sphincter can form ischiorectal abscesses.

- Posterior spread can lead to abscesses in the posterior anal or retrorectal spaces.

Perianal abscesses may also originate from other conditions such as perianal skin infections, trauma, anal fissures, internal hemorrhoids, medication injections, or sacrococcygeal osteomyelitis. Certain diseases, including Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, diabetes, and hematological disorders, may predispose to the development of perianal abscesses.

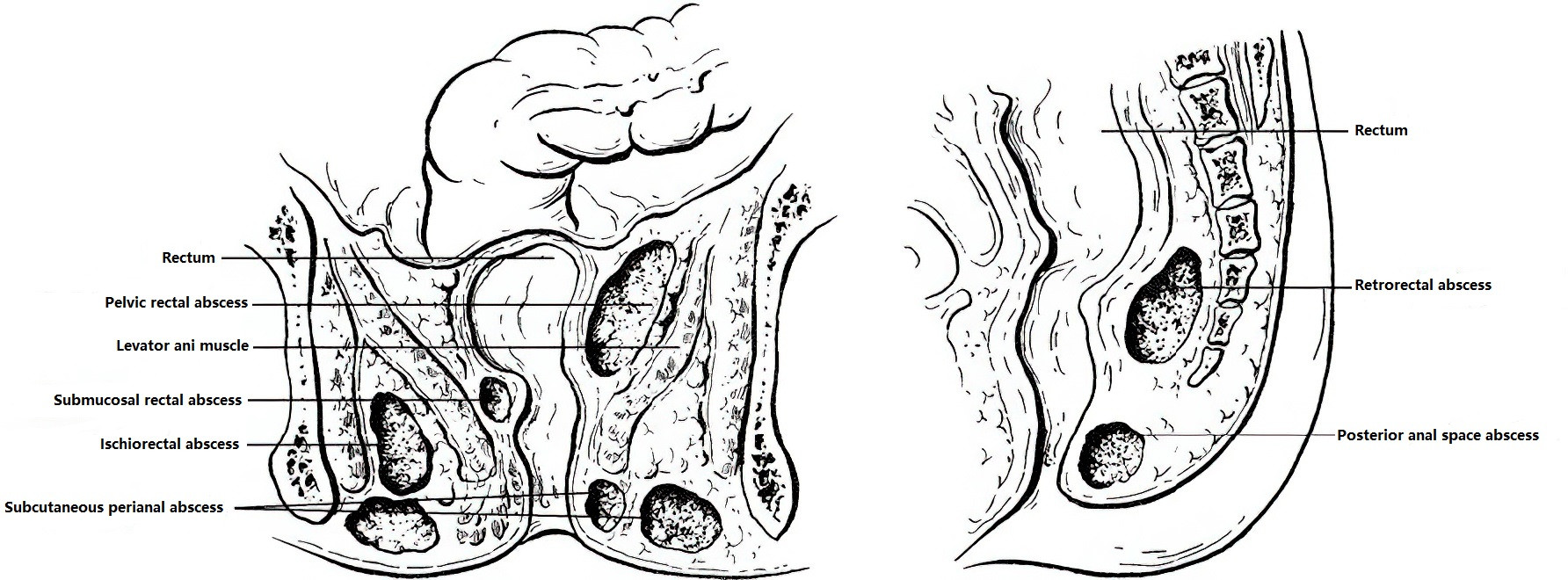

Classification

Perianal abscesses can be classified into low-level (below the levator ani muscle) and high-level (above the levator ani muscle) abscesses based on their anatomical location.

Figure 2 Locations of perianal abscesses

Low-Level Abscesses

These include subcutaneous perianal abscesses, ischiorectal abscesses, posterior intersphincteric abscesses, and low intersphincteric abscesses.

High-Level Abscesses

These include pelvic rectal abscesses, retrorectal abscesses, submucosal rectal abscesses, and high intersphincteric abscesses.

Clinical Manifestations

Subcutaneous Perianal Abscess

This is the most common type of abscess. It is typically located in the subcutaneous tissues posterior or lateral to the anus and tends to be localized. Patients often report significant localized pain, including persistent throbbing pain, but systemic symptoms are usually mild. The affected area may present with localized redness, swelling, tenderness, and a palpable fluctuant mass.

Ischiorectal Abscess

Also known as an ischiorectal space abscess, this is a relatively common type of abscess. It occurs within the ischiorectal fossa, often following the spread of infection from the anal glands through the external sphincter into the fossa. It may also develop from the downward progression of a deeper abscess. Due to the relatively large space of the ischiorectal fossa, the abscess can grow substantially, with the capacity of one side reaching 60–90 ml. Affected individuals experience persistent throbbing or distending pain on the affected side, which gradually worsens and becomes more severe with defecation or walking. Symptoms such as dysuria and tenesmus may also occur. In cases of larger abscesses, systemic signs of infection, including fever, chills, nausea, and fatigue, may become apparent. Early on, local findings may be minimal; however, as the abscess enlarges, redness, swelling, and asymmetry of the buttocks become more noticeable. Digital rectal examination or palpation reveals localized tenderness, increased skin temperature, and sometimes a fluctuant mass.

Pelvic Rectal Abscess

Also known as a pelvic rectal space abscess, this type is uncommon and occurs in the region above the levator ani muscle. Due to its deep location, it is often misdiagnosed. It may develop from the upward spread of an ischiorectal abscess that breaches the levator ani into the pelvic rectal space. Systemic symptoms are more pronounced, including high fever, chills, fatigue, and symptoms of septicemia. Patients often experience a sensation of rectal pressure or heaviness, sometimes accompanied by difficulty passing stool or urinating. However, local signs are usually minimal. A digital rectal examination may reveal a firm, tender, fluctuant bulge in the rectal wall, but perineal examination may show little to no abnormalities. Diagnosis can be confirmed through pus aspiration, endorectal ultrasonography, CT, or MRI imaging.

Other Types

These include submucosal rectal abscesses, retrorectal abscesses, and high intersphincteric abscesses. Because of their deeper locations, local symptoms are usually less obvious, with patients mainly reporting a sensation of heaviness or pressure in the perineal or rectal regions, worsening pain during defecation, and varying degrees of systemic infection symptoms. A digital rectal examination may detect a tender mass, and endorectal ultrasonography, CT, or MRI imaging plays a critical role in diagnosis and differentiation from other conditions.

Treatment

Treatment Principles

During the early stages of inflammation, before abscess formation, broad-spectrum antibiotics can be administered orally or via injection to prevent the spread of inflammation. However, the use of antibiotics may sometimes result in the deeper progression of the abscess and potentially worsen the infection. Once an abscess is confirmed, surgical treatment should be performed as soon as possible. The surgical approach varies depending on the location of the abscess.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics effective against Gram-negative bacilli are considered.

Warm Sitz Baths

This method helps alleviate symptoms.

Local Physical Therapy

This is used to promote healing.

Stool Softening

Laxatives or liquid paraffin are administered to ease defecation pain.

Surgical Treatment

Incision and drainage is the primary surgical method for treating perianal abscesses.

Incision and Drainage

This method is applicable for ischiorectal abscesses, pelvic rectal space abscesses, horseshoe-shaped abscesses, high-level abscesses, and cases where seton placement is not feasible. It forms the basis of other surgical techniques, although many patients undergoing this procedure will require a second surgery to address any resulting anal fistula.

Procedure

Under local or sacral anesthesia, a radial incision is made at the center of the abscess or where fluctuation is most evident. After draining the pus, the septal tissue within the abscess is carefully separated. The abscess cavity is flushed sequentially with 1% hydrogen peroxide solution and saline. A rubber drainage tube is placed, and the skin incision is trimmed into a fusiform shape to ensure unobstructed drainage.

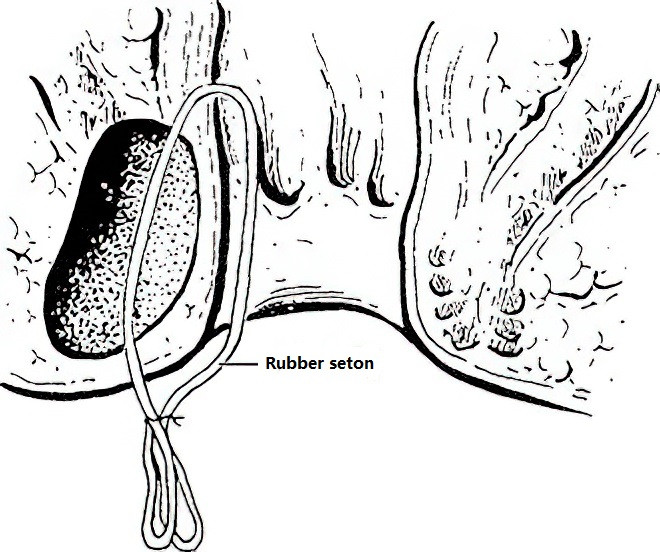

Incision and Seton Placement (Seton Therapy)

This procedure is suitable for ischiorectal abscesses, pelvic rectal space abscesses, retrorectal abscesses, anterior abscesses, high horseshoe-shaped abscesses, and abscesses in infants and young children. Seton placement is a technique that uses a rubber band or thread instead of a blade. The process involves gradual cutting, drainage, and healing. It reduces the risk of infection and limits the spread of inflammation. This method integrates four functions: cutting, drainage, marking, and stimulating wound healing through the presence of a foreign material.

Procedure

Under sacral anesthesia, a radial or arcuate incision is made at the point of abscess fluctuation or under the guidance of a puncture needle. After draining the pus, the septal tissue within the abscess cavity is separated, and the cavity is thoroughly rinsed with 1% hydrogen peroxide solution and saline. One finger is inserted into the rectum for guidance while a probe is inserted through the abscess cavity via the incision to locate the internal opening at the highest point of the cavity. A rubber seton is passed through the internal opening and pulled out of the external incision. The skin between the incision and the internal opening is then cut, bringing the internal and external openings together. Gentle tightening of the seton is performed, followed by ligation with a silk thread. This method has the advantage of curing the abscess in a single surgical procedure, thereby avoiding the need for an initial incision and drainage surgery followed by a secondary procedure for fistula repair after 2–3 months.

Figure 3 Incision and seton placement

Internal Opening Incision

This method is suitable for low anal fistula abscesses. It involves a one-time incision of the primary internal opening to accelerate healing but carries the risk of damaging the anal sphincter. Therefore, it is contraindicated in infants, anterior abscesses, and high-level abscesses.