Rectal cancer refers to malignancies occurring between the rectosigmoid junction and the dentate line. It is relatively common.

Etiology and Pathology

Etiology

The exact cause of rectal cancer remains unclear, though related factors are as described in the preceding section of this chapter.

Macroscopic Classification

Rectal cancer is classified into three types: ulcerative, exophytic, and infiltrative.

- Ulcerative Type: This type accounts for over 50% of cases and is the most common. Early lesions may present as ulcers, often with bleeding. It is poorly differentiated and prone to early metastasis.

- Exophytic Type: The tumor primarily projects into the intestinal lumen with minimal surrounding infiltration. It is associated with a relatively favorable prognosis.

- Infiltrative Type: This type is characterized by poor differentiation, early metastasis, and a poor prognosis.

Histological Classification

Adenocarcinoma

This is the most common histological type, which includes the following subtypes:

- Tubular Adenocarcinoma

- Papillary Adenocarcinoma

- Mucinous Adenocarcinoma: Displays higher malignancy.

- Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma: Highly malignant with a poor prognosis.

Adenosquamous Carcinoma

Also known as adenosquamous carcinoma, this tumor consists of both adenocarcinoma and squamous carcinoma cells and is often moderately to poorly differentiated. Adenosquamous carcinoma and squamous carcinoma are primarily found in the lower rectum and anal canal, though they are relatively rare.

Undifferentiated Carcinoma

This is characterized by diffuse sheets or clusters of tumor cells that do not form glandular structures. The cancer cells exhibit irregular arrangement, are smaller in size, and appear relatively uniform. This type is associated with a poor prognosis.

Colorectal cancers may exhibit two or more histological types within the same tumor, with varying degrees of differentiation. This diversity is attributed to differences in histological characteristics above and below the dentate line.

Clinical Pathological Staging

The staging system for rectal cancer is consistent with that of colon cancer.

Spread and Metastasis

Direct Invasion

The tumor initially infiltrates the deeper layers of the rectal wall. Longitudinal spread along the rectal wall occurs relatively late, and it is estimated that it takes about 1.5–2 years for the tumor to encircle the rectal wall completely. Direct invasion may penetrate the serosa and extend into adjacent organs such as the uterus, bladder, prostate, seminal vesicles, vagina, or ureters. Tumors in the lower rectum are particularly prone to surrounding tissue invasion due to the absence of a protective serosal layer.

Lymphatic Metastasis

This is the most common route of spread. Upper rectal cancers metastasize upwards along the superior rectal artery, inferior mesenteric artery, and lymph nodes surrounding the abdominal aorta. Lower rectal cancers (demarcated by the peritoneal reflection) primarily metastasize upwards and laterally. Research indicates that cancers located 2 cm above the tumor edge have a relatively low (2%) likelihood of positive lymph node involvement. Tumors near the dentate line may metastasize upward, laterally, or downward. Downward metastasis can manifest as inguinal lymph node enlargement.

Hematogenous Metastasis

Tumor cells may invade veins and spread via the portal vein to the liver. They can also metastasize through the iliac vein to the lungs, bones, or brain.

Seeding Metastasis

This is rare in rectal cancer, though upper rectal cancers may occasionally exhibit peritoneal seeding.

Symptoms

Rectal cancer typically lacks significant symptoms in the early stages. Symptoms often appear only when the tumor disrupts bowel movements or ulcerates and bleeds.

Rectal Irritation Symptoms

Symptoms include frequent defecation urges, changes in bowel habits, a sensation of incomplete evacuation, a feeling of perineal heaviness, and tenesmus. In advanced stages, lower abdominal pain may occur.

Symptoms of Tumor Ulceration and Bleeding

Stools may have visible blood and mucus, and in severe cases, stools may contain pus and blood.

Symptoms of Intestinal Lumen Narrowing

Tumor infiltration may lead to bowel narrowing. Initially, stools may progressively thin. Partial bowel obstruction may cause symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, hyperactive bowel sounds, and signs of incomplete intestinal obstruction.

Symptoms from Tumor Invasion of Surrounding Tissues or Distant Metastasis

Invasion of the prostate or bladder might result in urinary frequency, dysuria, or hematuria.

Vaginal invasion may lead to abnormal vaginal discharge.

Invasion of the presacral nerves may cause severe and persistent sacrococcygeal pain.

Advanced stages involving liver metastasis may present with ascites, jaundice, cachexia, and edema.

Local symptoms include rectal bleeding, frequent defecation, narrowed stools, mucous stools, anal pain, tenesmus, and constipation.

Signs

Detection of a Mass by Digital Rectal Examination

Approximately 70% of rectal cancers are categorized as low rectal cancers, which can often be palpated during a digital rectal examination (DRE). Consequently, DRE is the most critical physical examination for diagnosing low rectal cancers.

However, the reach of DRE is limited to approximately 8 cm above the anal verge. The absence of a palpable mass does not exclude the possibility of lesions in the proximal rectum or colon. For cases involving rectal bleeding, positive fecal occult blood tests, or blood-stained gloves during DRE, further investigation with colonoscopy is necessary to determine the source of bleeding. The specifics of DRE are discussed in Section 2 of this chapter.

Inguinal Lymph Node Enlargement

Due to differences in lymphatic drainage above and below the dentate line, metastasis to the inguinal lymph nodes is rare in rectal cancer. Inguinal lymph node enlargement is more commonly seen in cases of rectal cancer involving regions below the dentate line.

Complications or Late-Stage Signs

Intestinal Obstruction

Symptoms may include abdominal distension and hyperactive bowel sounds.

Liver Metastases

This may present as hepatomegaly, jaundice, or positive findings of shifting dullness.

Late-Stage Manifestations

These can include malnutrition or cachexia.

Auxiliary Examinations

Laboratory Tests

Similar to colon cancer, rectal cancer lacks highly sensitive and specific laboratory tests.

Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT)

Due to its affordability, FOBT can serve as an initial screening tool for colorectal cancer. Positive results warrant further diagnostic testing.

Tumor Markers

Markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA19-9 may be evaluated.

Endoscopic Examination

Endoscopy, with biopsy for pathological diagnosis, is essential prior to initiating surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. This is therefore considered the most critical adjunctive test for rectal cancer.

Unless contraindicated (e.g., due to bowel obstruction), a fiberoptic colonoscopy should be performed before surgery in cases of diagnosed rectal cancer. This is due to the 5–10% likelihood of synchronous multiple primary tumors in the colorectal region. In cases where preoperative obstruction prevents fiberoptic colonoscopy, the proximal segments of the obstruction should be examined within six months postoperatively to rule out multiple primary cancers.

Imaging Studies

Imaging is used for clinical staging, prognosis evaluation, and treatment planning.

Endorectal Ultrasound

Owing to its accuracy in T-staging, as well as its affordability and convenience, endorectal ultrasound is the first choice for staging T2 and earlier rectal cancers.

Pelvic Contrast-Enhanced MRI

MRI is recommended for rectal cancer as it not only evaluates tumor invasion depth and lymph node metastasis but also provides critical information on whether the mesorectal fascia is involved.

Chest, Abdominal, and Pelvic Contrast-Enhanced CT

CT scans are primarily used to assess distant metastases, particularly in the liver and lungs.

Whole-Body PET-CT

PET-CT is superior to CT and MRI in distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions. Due to its high cost, PET-CT is primarily recommended in two scenarios:

- When new lesions (if present) might influence the feasibility of surgical resection, such as an unresectable brain metastasis rendering attempts to remove liver metastases or locally recurrent tumors palliative rather than curative.

- To characterize suspicious lesions identified via CT, such as distinguishing between postoperative local inflammatory changes and tumor recurrence.

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of rectal cancer can generally be established based on the patient’s medical history, physical examination, endoscopic findings, and imaging studies. However, the diagnosis is often delayed to varying extents. This may be attributed to patients’ lack of attention to symptoms such as rectal bleeding or changes in bowel habits, as well as insufficient vigilance on the part of healthcare providers.

Treatment

Surgery is the primary curative treatment for rectal cancer. Preoperative (neoadjuvant) and postoperative (adjuvant) radiotherapy and chemotherapy may improve the chances of cure to some extent. Palliative treatment is applied to advanced rectal cancer cases unsuitable for curative surgery, with the principles of alleviating pain, improving quality of life, and prolonging survival.

Surgery

Extensive clinical and pathological studies have shown that the distal intramural spread of rectal cancer is smaller than that of colon cancer, with only about 2% of rectal cancers spreading more than 2 cm distally. This finding is an essential consideration for choosing surgical methods.

Local Excision

There are two approaches: transanal or transsacral. It requires en bloc resection of the tumor through the full thickness of the rectal wall with a minimum of a 3-mm clear margin.

Since no regional lymph node dissection is performed, the absence of pathological evaluation of lymph node metastasis results in a higher recurrence risk compared to radical surgery.

If the pathology reveals positive margins, a submucosal invasion depth >1 mm, lymphovascular invasion, or poor differentiation (high-risk factors for local recurrence), a radical resection should be added.

Indications

Early-stage tumors that are small, classified as T1N0, and well-differentiated. It is particularly suitable for patients who are not fit for radical surgery.

Radical Rectal Resection

This involves en bloc resection of the cancerous mass along with adequate margins, regional lymph nodes, accompanying vasculature, and the entire mesorectum.

The main surgical approaches include:

- Abdominoperineal Resection (Miles Surgery)

- Low Anterior Resection (Dixon Surgery)

- Hartmann Surgery

During surgery, attention should be paid to preserving urinary and sexual functions as much as possible to maintain the patient’s quality of life.

Laparoscopic radical rectal surgery is preferred as it minimizes trauma and facilitates quicker recovery. In centers with advanced facilities, robotic or laparoscopic-assisted surgery can be considered.

If rectal cancer invades the uterus, a posterior pelvic exenteration (removal of the uterus along with the rectal tumor) can be performed. For invasion of the bladder, a total pelvic exenteration (rectum and bladder resection in males; or rectum, uterus, and bladder in females) may be needed.

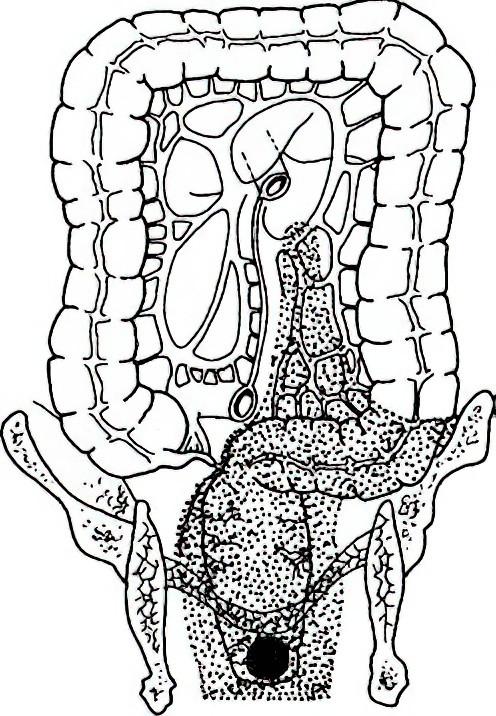

Abdominoperineal Resection (Miles Surgery)

Developed by Miles in 1908, this involves a combined abdominal and perineal approach for en bloc resection of the tumor along with lymphatic clearance.

Figure 1 Miles surgery

Resection Range

The entire rectum, inferior mesenteric artery and associated lymph nodes, the entire mesorectum, levator ani muscle, ischiorectal fossa fat, anal canal, 3–5 cm of perianal skin and subcutaneous tissue, and all anal sphincters. A permanent sigmoid colostomy is performed in the left lower quadrant.

Indications

This is indicated in external anal sphincter or levator ani involvement, or patients with pre-existing anal incontinence.

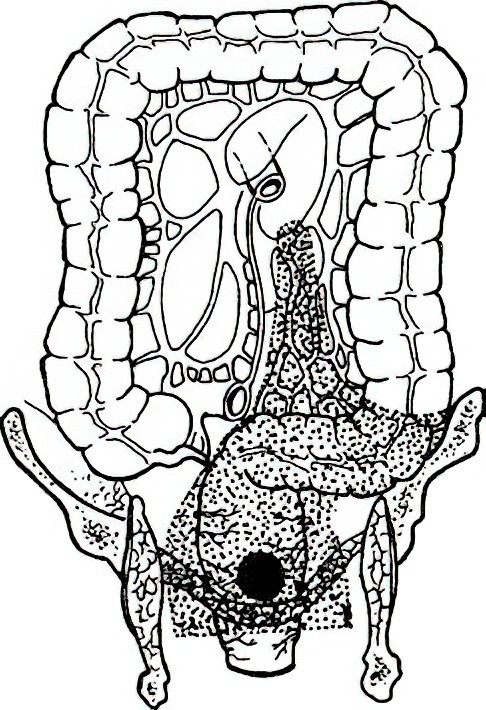

Low Anterior Resection (Dixon Surgery)

Introduced by Dixon in 1948, this sphincter-preserving surgery involves tumor resection followed by primary anastomosis to restore bowel continuity. It is currently the most commonly performed radical rectal resection.

Figure 2 Dixon surgery

Surgical principles require a tumor-free distal margin of at least 2 cm (or 1 cm for low rectal cancers).

Indications

As long as the external anal sphincter and levator ani remain uninvolved, and there is no anal incontinence, patients can undergo a low colorectal anastomosis (Dixon) or an ultra-low coloanal anastomosis (e.g., Parks surgery or intersphincteric resection). Long-term survival and recurrence-free survival are comparable to abdominoperineal resection.

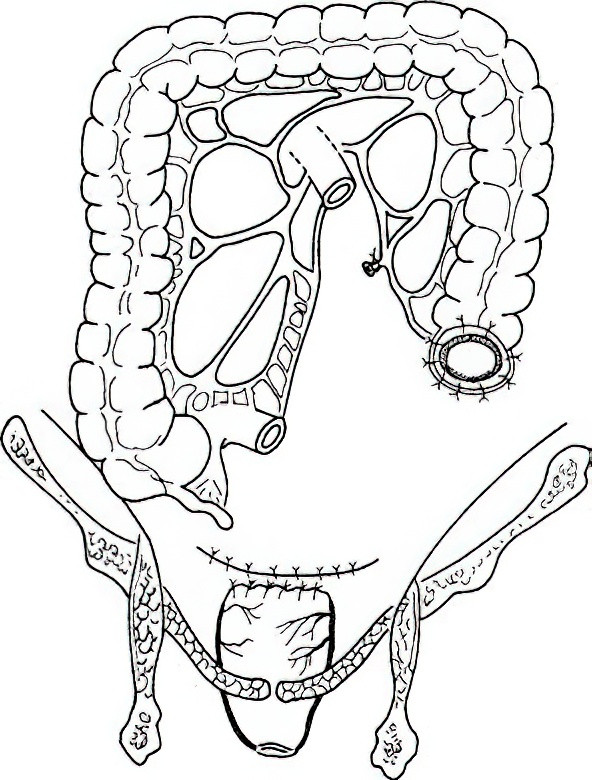

Hartmann Surgery

Proposed by Hartmann in 1921, this procedure involves rectal cancer resection followed by proximal colostomy and distal rectal stump closure.

Figure 3 Hartmann Surgery

Indications

This is indicated in patients in poor general condition who cannot tolerate Miles surgery or those with acute obstruction who are unfit for Dixon surgery.

Palliative Surgery

In advanced rectal cancer cases, the principle of palliative surgery is to alleviate symptoms and manage complications, without necessarily addressing the primary tumor.

For defecation difficulties or obstruction, a double-barrel sigmoid colostomy may be performed.

For uncontrollable tumor bleeding, palliative tumor resection may be considered.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy uses targeted radiation to kill tumor cells in the radiation field and is classified as a local treatment. Perioperative radiotherapy may increase the chances of cure, while palliative radiotherapy helps in symptom relief.

Preoperative Radiotherapy

This is recommended for tumors with high-risk features, such as deep invasion, mesorectal fascia involvement, or advanced disease as assessed on imaging. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy can shrink the tumor, downstage it, increase surgical resection rates, and reduce local recurrence.

Clinical guidelines mandate neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for T4 mid-to-low rectal cancer and recommend it for T3 cases as well.

Postoperative Radiotherapy

Postoperative radiotherapy is less effective than preoperative and is only indicated when the patient has not received preoperative radiotherapy and pathological findings indicate high recurrence risk (e.g., positive circumferential resection margin, T4b, or nodal involvement such as N1c/N2).

Palliative Radiotherapy

For unresectable advanced or recurrent rectal cancer, radiotherapy can relieve local symptoms and avoid surgery.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological treatment leverages the high sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic drugs for selective tumor cell eradication. Administration methods include systemic intravenous delivery, localized sustained-release granules, or postoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Chemotherapy for colorectal cancer is typically fluorouracil-based, with systemic intravenous chemotherapy as the primary approach.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy

Systemic adjuvant chemotherapy after radical surgery improves the 5-year survival rate for high-risk stage II and stage III colorectal cancer. Two primary regimens are currently employed, each lasting 3–6 months:

- FOLFOX Regimen: Oxaliplatin and calcium folinate are administered via intravenous infusion on the first day, followed by a continuous infusion of fluorouracil over 48 hours. This cycle is repeated every two weeks.

- CAPEOX Regimen: Oxaliplatin is infused intravenously on the first day, followed by oral administration of the fluorouracil precursor capecitabine for two weeks. This cycle is repeated every three weeks, with efficacy similar to the FOLFOX regimen.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

The current standard neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer is fluorouracil-based radiosensitization during radiotherapy. Recent studies have demonstrated that neoadjuvant chemotherapy can also achieve tumor downstaging and increase surgical resection rates. In areas where radiotherapy is not yet available, cautious use of chemotherapy regimens such as FOLFOX or CAPEOX, potentially supplemented with additional standard chemotherapeutic or molecular-targeted agents, may be considered.

Other Pharmacological Treatments

Additional treatment options include irinotecan and molecular-targeted drugs such as bevacizumab and cetuximab, which antagonize vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), respectively.

Recent studies have shown that checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 have become first-line treatments for patients with mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) or high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) colorectal cancer in advanced stages. Furthermore, neoadjuvant immunotherapy has demonstrated promising short-term efficacy for dMMR or MSI-H colorectal cancer, particularly in preserving anal function for ultra-low rectal cancers.

Local Chemotherapy

Although supported by limited high-level evidence, localized chemotherapy methods—such as intraperitoneal drug placement, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), and transarterial hepatic chemotherapy—have been implemented in clinical practice. Their role in rectal cancer treatment remains to be clearly defined through further clinical research.

Other Treatment Options

For rectal cancer causing obstruction in patients who are not candidates for surgery, alternatives such as metal stent placement, intestinal decompression tube insertion, or colostomy may be employed to alleviate obstruction. For unresectable multiple liver metastases, ultrasound- or CT-guided interventional ablation may be used to minimize lesions. Supportive care should remain a priority for advanced-stage patients, with a focus on improving quality of life.