Colon cancer is a common malignant tumor. Approximately 70% of colon cancers develop from adenomatous polyps, while about 30% present directly as cancer nests without an adenoma stage. Morphologically, stages of hyperplasia, adenoma, and malignancy can be observed, along with associated chromosomal changes. It is generally recognized that the development and progression of colon cancer involve a multistep, multiphase, and multigene process.

The progression from adenoma to carcinoma typically takes 10–15 years. During this period, genetic mutations include oncogene activation (e.g., KRAS, c-MYC, EGFR), inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (e.g., APC, DCC, P53), mismatch repair gene mutations (e.g., MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, MSH6), and gene overexpression (e.g., COX2, CD44v). APC gene inactivation leads to loss of heterozygosity, initiating the APC/β-catenin pathway and promoting the adenoma process. Mutations in mismatch repair genes result in genetic instability, which can lead to hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC), now referred to as Lynch syndrome.

Although the exact causes of colon cancer remain unclear, numerous high-risk factors have been identified, such as adenomatous polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, family history, high intake of fat and protein, insufficient dietary fiber, advanced age, obesity, and smoking. Hereditary predisposition plays a significant role in colon cancer pathogenesis. For instance, family members of individuals carrying mismatch repair gene mutations associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer are considered a high-risk population. Certain conditions, such as familial adenomatous polyposis, are well-established precancerous lesions. Additionally, colon adenomas, ulcerative colitis, and granulomas caused by schistosomiasis have notable links to the development of colon cancer.

Pathology and Classification

Based on gross tumor morphology, three types are identified:

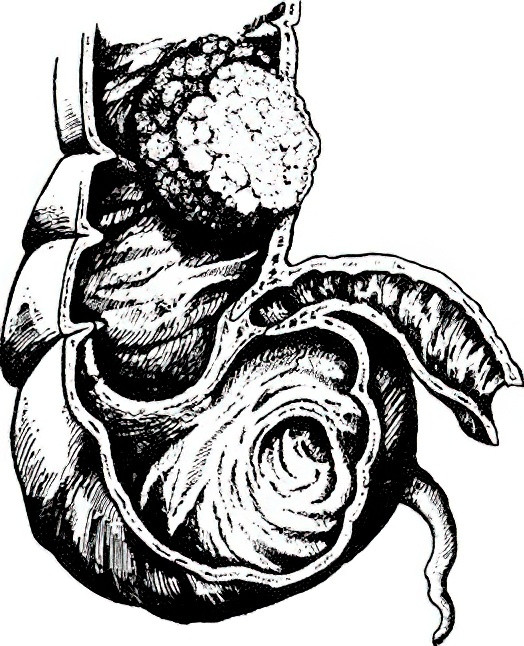

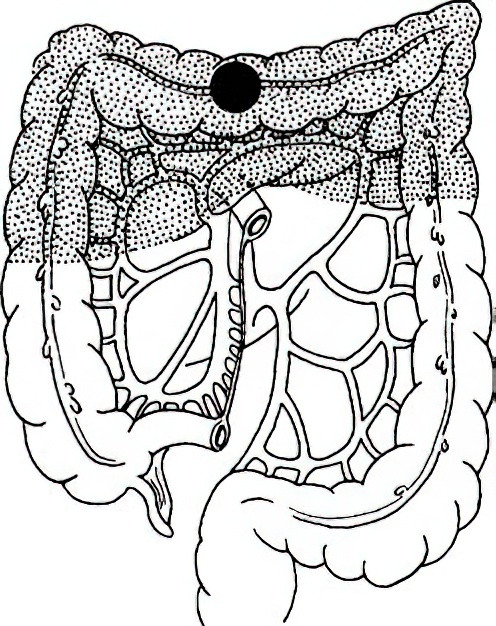

- Exophytic type: Tumors grow into the intestinal lumen and frequently occur in the right colon, particularly the cecum.

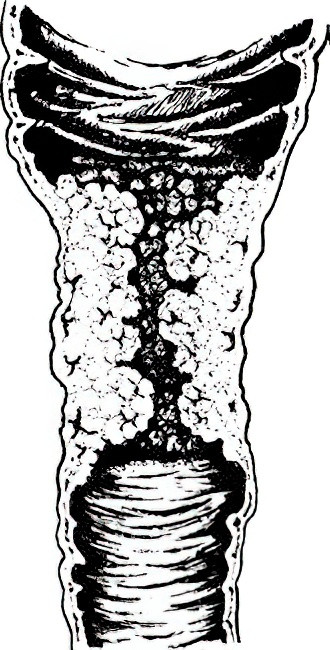

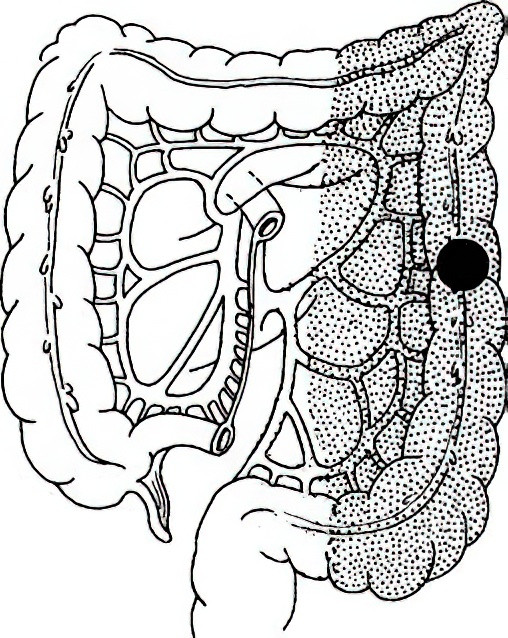

- Infiltrative type: Tumors infiltrate the intestinal wall, commonly causing luminal narrowing and obstruction, with a predilection for the left colon.

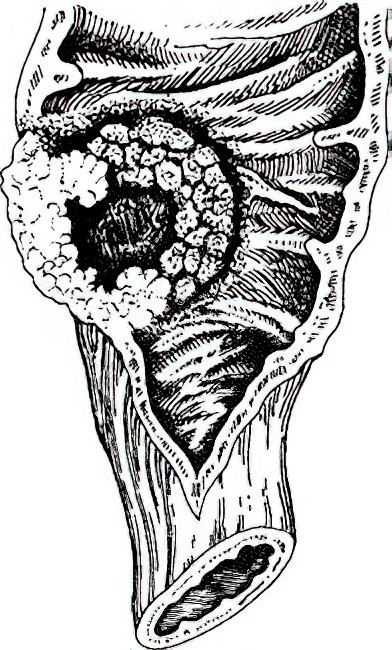

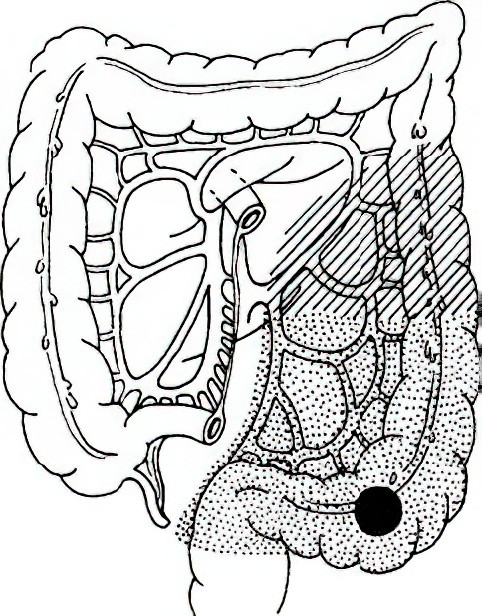

- Ulcerative type: Characterized by deep growth into the intestinal wall and infiltration of surrounding tissues, this is the most common type of colon cancer.

Figure 1 Exophytic colon cancer

Figure 2 Infiltrative colon cancer

Figure 3 Ulcerative colon cancer

Histological classification is based on the same criteria as rectal cancer.

Staging

The purpose of cancer staging is to understand the tumor's progression, guide effective treatment planning, and evaluate prognosis.

TNM Staging System

T (Primary Tumor):

Tx: Primary tumor cannot be assessed.

T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

Tis: Carcinoma in situ.

T1: Tumor invades submucosa.

T2: Tumor invades muscularis propria.

T3: Tumor penetrates through muscularis propria into the subserosa or into nonperitonealized pericolic/perirectal tissues.

T4: Tumor perforates visceral peritoneum or directly invades other organs or structures.

N (Regional Lymph Nodes):

Nx: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed.

N0: No regional lymph node metastasis.

N1: Metastasis in 1–3 regional lymph nodes.

N1a: One lymph node.

N1b: 2–3 lymph nodes.

N1c: Tumor deposits in the subserosa, mesentery, or nonperitonealized pericolic/perirectal tissues without regional lymph node involvement.

N2: Metastases in four or more regional lymph nodes.

M (Distant Metastasis):

Mx: Distant metastasis cannot be assessed.

M0: No distant metastasis.

M1: Presence of distant metastasis.

Relationship Between TNM Staging and Prognosis

TNM staging provides an objective reflection of prognosis in colorectal cancer. Data indicate the following 5-year survival rates:

- Stage I: 93%

- Stage II: 80%

- Stage III: 60%

- Stage IV (curative resection possible): 30%

- Stage IV (palliative treatment): 8%

Patterns of Metastasis

Lymphatic spread is the primary route of metastasis. Cancer cells first spread to pericolic and paracolic lymph nodes, followed by mesenteric vascular nodes and mesenteric vascular root nodes. Hematogenous metastasis most commonly affects the liver, followed by the lungs and bones. Direct invasion into adjacent organs can also occur; for example, sigmoid colon cancer often invades the bladder, uterus, or ureters, while transverse colon cancer may invade the stomach, sometimes forming internal fistulas. Shed cancer cells may also lead to peritoneal implantation metastasis.

Clinical Manifestations

Colon cancer often presents without obvious symptoms in its early stages. As the disease progresses, the following symptoms commonly develop:

- Changes in bowel habits and stool characteristics: These are typically the earliest signs and may include increased frequency of bowel movements, diarrhea, constipation, and stool with blood, pus, or mucus.

- Abdominal pain: Another potential early symptom, this often manifests as vague, persistent dull pain without precise localization, or as abdominal discomfort or bloating. Pain worsens or may become colicky when intestinal obstruction occurs.

- Abdominal mass: This is most commonly the tumor itself but may sometimes be due to fecal accumulation proximal to an obstruction. Tumors of the transverse or sigmoid colon may exhibit some degree of mobility. If the tumor penetrates surrounding tissues and becomes infected, the mass becomes fixed and tender, with noticeable pain upon palpation.

- Symptoms of intestinal obstruction: These are usually indicative of chronic low-grade partial obstruction. When complete obstruction occurs, symptoms intensify. Acute complete colorectal obstruction may occasionally be the initial manifestation of tumors in the left colon.

- Systemic symptoms: These include anemia, weight loss, fatigue, and low-grade fever. With advanced disease, hepatomegaly, jaundice, edema, ascites, pelvic masses, supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, and cachexia may develop.

Differences in pathological type and tumor location influence clinical presentation. Tumors in the right colon typically feature a larger lumen and are more often exophytic, leading to a predisposition for necrosis, bleeding, and infection. As a result, symptoms such as abdominal pain, abdominal mass, and systemic manifestations are more prominent. In contrast, tumors in the left colon are typically infiltrative and cause luminal narrowing and obstruction. Symptoms in these cases are more likely to involve bowel habit changes, altered stool characteristics, and signs of obstruction. Molecular biological differences between left and right colon cancers are significant, influencing drug sensitivity and prognosis.

Diagnosis

Early symptoms of colon cancer are often mild and easily overlooked. Individuals over 40 years of age exhibiting any of the following conditions are considered high-risk:

- A first-degree relative with a history of colorectal cancer.

- A personal history of cancer, intestinal adenomas, or polyps.

- Positive fecal occult blood test results.

- Two or more of the following symptoms or conditions: mucus and bloody stools, chronic diarrhea, chronic constipation, a history of chronic appendicitis, or a history of psychological trauma.

For high-risk individuals, fiberoptic colonoscopy is valuable, with biopsy aiding definitive diagnosis when lesions are detected. Ultrasonography and CT scans provide assistance in evaluating abdominal masses, enlarged lymph nodes, and potential liver metastases. Serological markers, including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), are elevated in approximately 45% and 30% of colon cancer patients, respectively, though their specificity in diagnosing colon cancer is limited. Instead, they are more useful for postoperative prognosis and recurrence monitoring. Currently, molecular biomarkers such as KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF gene mutations, mismatch repair protein (MMR) expression, and microsatellite instability (MSI) are widely utilized for developing comprehensive treatment plans and assessing prognosis. Additionally, the early screening of colorectal cancer through fecal molecular markers is gaining popularity.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for colon cancer includes conditions such as colon polyps, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, intestinal tuberculosis, chronic bacterial dysentery, schistosomiasis, and amebic colitis. Histological examination of biopsy samples obtained via colonoscopy remains the most reliable method for distinguishing between these conditions.

Treatment

The treatment strategy primarily involves comprehensive therapy centered on surgical resection. The surgical approach includes complete mesocolic excision (CME), which emphasizes preserving mesocolic integrity to ensure complete tumor removal, extensive regional lymph node dissection, and minimizing injury to surrounding organs, blood vessels, and nerves.

Radical Surgery for Colon Cancer

Radical procedures require en bloc resection of the tumor along with at least 10 cm of bowel on both the proximal and distal sides, including the mesentery and regional lymph nodes. Common surgical techniques include the following:

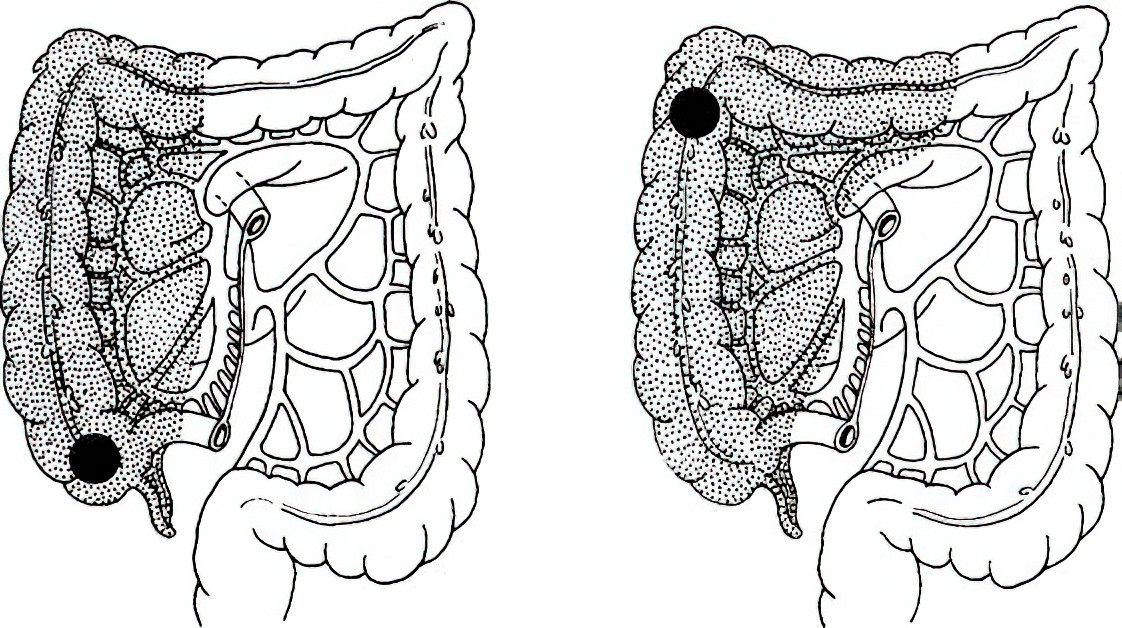

Right Hemicolectomy

This is indicated for cancers of the cecum, ascending colon, and hepatic flexure. For cancers of the cecum and ascending colon, the resection involves the right half of the transverse colon, ascending colon, cecum, and approximately 15–20 cm of the terminal ileum, with an ileocolic anastomosis. For hepatic flexure tumors, in addition to the aforementioned areas, lymph nodes of the transverse colon and gastrocolic ligament adjacent to the right gastroepiploic artery are included in the resection.

Figure 4 Extent of right hemicolectomy

Transverse Colectomy

This is indicated for tumors in the middle segment of the transverse colon. This procedure includes resection of approximately 10 cm of bowel on either side of the tumor, along with the associated lymph nodes and the lymph nodes of the gastrocolic ligament. In many cases, it necessitates the removal of the entire transverse colon, including the hepatic and splenic flexures, with an anastomosis created between the ascending and descending colons. If excessive tension prevents an anastomosis, the descending colon may also be resected in cases of left-transverse colon tumors, followed by an ascending-sigmoid colon anastomosis.

Figure 5 Extent of transverse colectomy

Left Hemicolectomy

This is indicated for splenic flexure and descending colon tumors. Resection typically includes the left portion of the transverse colon and the descending colon. Depending on the tumor's location within the descending colon, part or all of the sigmoid colon may also be excised, with subsequent anastomosis between colonic segments or between the colon and rectum.

Figure 6 Extent of left hemicolectomy

Sigmoidectomy

This is indicated for cancers of the sigmoid colon. Depending on the length of the sigmoid colon and the location of the tumor, this may involve resection of the entire sigmoid colon and the descending colon, or the entire sigmoid colon along with portions of the descending colon and rectum, followed by a colonic-rectal anastomosis.

Figure 7 Extent of sigmoidectomy

Surgery for Colon Cancer with Acute Intestinal Obstruction

Surgery for colon cancer complicated by obstruction typically proceeds after adequate preoperative preparation, including gastrointestinal decompression and correction of fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base imbalances. For right colon cancer, right hemicolectomy with primary ileocolic anastomosis is performed. In cases where the patient's condition precludes this, options include placing a decompression tube or creating a cecostomy to relieve obstruction, followed by radical resection later. For left colon cancer with acute obstruction, treatment options include resection with primary anastomosis, placement of a stent to relieve obstruction prior to radical surgery, and intraoperative bowel irrigation followed by anastomosis if stool burden is significant.

In cases of significant bowel dilation and edema, resection of the tumor may be followed by proximal colostomy and distal stump closure. If the tumor cannot be resected, a proximal transverse colostomy can be created at the site of obstruction. Postoperatively, conversion therapy may reduce the tumor size and stage, allowing for reevaluation of eligibility for radical resection in a second-stage surgery. For unresectable tumors, options include palliative colostomy, bypass procedures, stent placement, or decompression tube insertion, all of which are viable and effective options.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological treatment details are as outlined for rectal cancer.