Acute appendicitis is a common surgical condition and the most frequent cause of acute abdomen. Fitz first accurately described the disease’s history, clinical manifestations, and pathological findings in 1886, and proposed appendectomy as a rational treatment. Advances in surgical techniques, anesthesia, antibiotics, and postoperative care have enabled most patients to receive early diagnosis and appropriate management, resulting in favorable outcomes. However, diagnostic and treatment complexities persist in certain cases, necessitating careful evaluation of each individual patient.

Etiology

The predisposition of the appendix to inflammation is attributed to its anatomical characteristics. It is a narrow blind-ended tube rich in microorganisms, with abundant lymphoid tissue in its walls, making it susceptible to infection. Acute appendicitis is generally considered to result from a combination of factors:

Appendiceal Lumen Obstruction

This is the most common cause of acute appendicitis. The most frequent cause of obstruction is significant lymphoid hyperplasia, accounting for approximately 60% of cases and occurring frequently in younger individuals. Fecaliths are another cause, responsible for about 35% of cases. Less commonly, obstruction may result from foreign bodies, inflammatory strictures, food residues, ascarid worms, or tumors. Narrowness of the appendiceal lumen, a small orifice, and a short mesentery contributing to a coiled shape are structural factors that predispose to obstruction. After lumen obstruction, mucus secretion continues within the appendix, leading to increased intraluminal pressure, impaired blood flow, and exacerbation of the inflammation.

Bacterial Invasion

Luminal obstruction creates an environment for bacterial proliferation. Bacteria release endotoxins and exotoxins that damage the mucosal epithelium and cause ulcers. The bacteria penetrate through the ulcerated mucosa into the muscularis. The resulting increased interstitial pressure impedes arterial blood flow, causing ischemia and eventually leading to necrosis and gangrene. Pathogenic bacteria are often Gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes from the intestinal tract.

Other Factors

Congenital anomalies of the appendix, such as excessive length, twisting, narrowed lumen, or poor vascular supply, contribute to inflammatory susceptibility. Gastrointestinal dysfunction causing visceral nerve reflexes may lead to muscle and vascular spasms in the intestinal tract, causing mucosal damage and bacterial invasion, culminating in acute inflammation.

Clinical Pathological Classification

The clinical course and pathological changes of acute appendicitis can be categorized into four types:

Acute Simple Appendicitis

This mild form represents the early stage of appendicitis. The lesions are often confined to the mucosal and submucosal layers. The appendix shows mild swelling, congestion of the serosa, and loss of its normal luster, with small amounts of fibrinous exudates on the surface. Microscopically, there is edema and neutrophil infiltration in all layers of the appendix, with small mucosal ulcers and punctate hemorrhages. Clinical symptoms and signs are generally mild.

Acute Suppurative Appendicitis

Also known as acute phlegmonous appendicitis, it frequently progresses from simple appendicitis. The appendix appears markedly swollen with severe congestion of the serosa, covered by fibrinous (purulent) exudates. Microscopically, the ulcers on the mucosa extend deeper into the muscularis and serosa, with small abscesses forming in the wall and pus accumulating in the lumen. Surrounding peritoneal fluid may contain thin pus, causing localized peritonitis. Clinical symptoms and signs are more pronounced.

Gangrenous and Perforated Appendicitis

This is a severe form of appendicitis. Necrosis, partial or full-thickness, affects the appendix wall, giving it a dark purple or black appearance. The lumen is filled with pus, and increased pressure within the appendix contributes to vascular compromise. Perforations often occur at the base or tip of the appendix. When perforations are not sealed off, infection spreads, potentially leading to acute diffuse peritonitis.

Periappendiceal Abscess

In cases of suppuration, gangrene, or perforation, slow progression allows the omentum to migrate to the right lower quadrant, surrounding the appendix and forming adhesions, leading to an inflammatory mass or periappendiceal abscess.

The potential outcomes of acute appendicitis include the following:

Resolution of Inflammation

Some cases of simple appendicitis resolve with prompt medical therapy, though the majority progress to chronic appendicitis, with recurrent episodes.

Localized Inflammation

Suppurative, gangrenous, or perforated appendicitis may be localized by omental adhesions, forming a periappendiceal abscess. Treatment often requires high-dose antibiotics or conventional medicine, but recovery may be slow.

Spread of Inflammation

Severe or rapidly progressing appendicitis that is neither surgically addressed nor effectively confined by omental adhesions may spread, leading to diffuse peritonitis, suppurative pylephlebitis, or septic shock.

Clinical Diagnosis

Diagnosis primarily relies on a patient’s medical history, clinical symptoms, physical examination findings, and laboratory tests.

Symptoms

Abdominal Pain

Typical abdominal pain begins in the upper abdomen, gradually migrates to the periumbilical region, and after several hours (6–8 hours), localizes to the right lower quadrant (RLQ). The duration of this process depends on the severity of the disease and the anatomical position of the appendix. Approximately 70%–80% of patients exhibit this characteristic migratory pain. In some cases, initial pain occurs directly in the RLQ. The type of abdominal pain varies with different types of appendicitis:

- Simple appendicitis presents with mild, dull pain.

- Suppurative appendicitis manifests as paroxysmal distension pain or severe colicky pain.

- Gangrenous appendicitis causes continuous severe pain.

- Perforated appendicitis may initially lead to temporary pain relief due to the sudden drop in intraluminal pressure, but pain intensifies again when peritonitis develops.

The location of abdominal pain also varies depending on the position of the appendix. For example, retrocecal appendicitis may cause pain in the right flank, pelvic appendicitis may cause suprapubic pain, and subhepatic appendicitis may lead to right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain. Rarely, a left lower quadrant appendix results in pain in the left lower abdomen.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Early symptoms may include anorexia. Nausea and vomiting can also occur but are usually mild. Some cases may present with diarrhea. In pelvic appendicitis, inflammatory irritation of the rectum and bladder may cause tenesmus or urinary urgency and frequency. When diffuse peritonitis develops, it may lead to paralytic ileus, resulting in abdominal distension and reduced gas or stool passage.

Systemic Symptoms

General fatigue may appear in the early phase. Severe inflammation can cause systemic toxicity characterized by tachycardia and fever, often around 38°C. Appendiceal perforation may lead to higher fevers, reaching 39°C–40°C. In cases of pylephlebitis, symptoms such as chills, high fever, and mild jaundice can occur. Extensive abdominal cavity infections due to purulent, gangrenous, or perforated appendicitis with diffuse peritonitis can result in hypovolemia, sepsis, and even dysfunction of other organs.

Physical Signs

RLQ Tenderness

RLQ tenderness is the most common and significant physical sign of acute appendicitis. Tenderness is typically located at McBurney’s point but can shift according to variations in appendiceal location. However, the tenderness remains consistently localized. Even before the pain migrates to the RLQ, localized tenderness in this area may already be present. The severity of tenderness correlates with the degree of inflammation. In elderly patients, tenderness may be less pronounced. As inflammation progresses, the area of tenderness may expand. If perforation occurs, tenderness may become diffuse, affecting the entire abdomen, although maximal tenderness remains at the appendiceal location. Tenderness may be assessed more accurately through percussion. Examination in the left lateral decubitus position may enhance diagnostic accuracy.

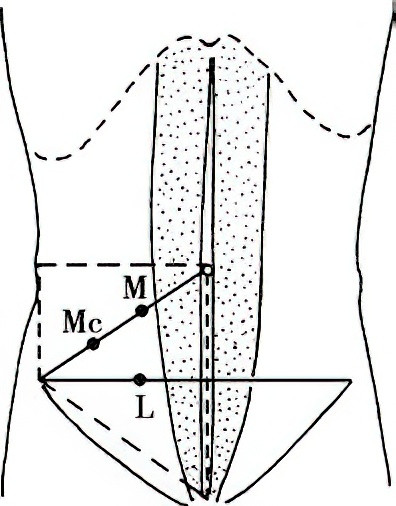

Figure 1 Tenderness points in appendicitis

M: Morris point; Mc: McBurney point; L: Lenz point.

The dashed quadrilateral outlines the Rapp tenderness zone.

Signs of Peritoneal Irritation

Signs such as rebound tenderness (Blumberg sign), abdominal muscle rigidity, and reduced or absent bowel sounds reflect peritoneal inflammation and increase in severity with suppuration, gangrene, or perforation. The extent of peritoneal irritation correlates with the degree of local exudation or spread of appendiceal perforation. However, signs of peritoneal irritation may be less apparent in children, elderly patients, pregnant women, obese individuals, or debilitated patients, as well as in cases of retrocecal appendicitis.

RLQ Mass

A palpable, tender mass in the RLQ with unclear borders and significant fixation on physical examination suggests a diagnosis of periappendiceal abscess.

Other Diagnostic Signs

Rovsing's Sign

In the supine position, applying pressure to the left lower abdomen while compressing the proximal colon may lead to right lower quadrant pain due to the transmission of gas to the cecum and appendix, indicating a positive test.

Psoas Sign

In the left lateral decubitus position, passive extension of the right thigh may cause pain in the RLQ, indicating a positive test. This suggests that the appendix is anterior to the psoas muscle or located retrocecal or retroperitoneally.

Obturator Sign

In the supine position, passive internal rotation of the right hip and thigh, after flexing them, may cause pain in the RLQ, indicating a positive test and implying that the appendix is near the obturator internus muscle.

Digital Rectal Examination

Tenderness at the location of the inflamed appendix can occur during rectal examination, often felt at the anterior right rectal wall. Widespread tenderness may be detected with perforation, and at times a tender mass may be palpable in cases of periappendiceal abscess formation.

Laboratory Tests

Most patients with acute appendicitis exhibit an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and increased neutrophil proportions. WBC counts often rise to (10–20) × 109/L, with a left shift in the neutrophil distribution. Some patients, particularly those with simple appendicitis or elderly individuals, may not show significant leukocytosis. Routine urinalysis is generally unremarkable, but a few red blood cells may appear when the inflamed appendix is adjacent to the ureter or bladder. Hematuria suggests primary urinary tract pathology. In women of reproductive age with a history of missed menstrual periods, serum β-HCG levels should be checked to exclude obstetric conditions. Serum amylase and lipase tests may help exclude acute pancreatitis.

Imaging Studies

Abdominal X-ray

Findings may show cecal distension, air-fluid levels, or occasionally calcified fecaliths or foreign bodies, aiding in diagnosis.

Ultrasound

Diagnostic findings include an enlarged appendix or presence of an abscess.

CT Scan

CT has greater sensitivity than ultrasound, particularly useful in diagnosing periappendiceal abscesses. These imaging modalities are not mandatory for diagnosing acute appendicitis and are usually reserved for uncertain cases.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy directly visualizes the appendix and can differentiate appendicitis from other conditions with similar symptoms. It is definitive for confirming the diagnosis and allows for laparoscopic appendectomy. For cases where the diagnosis is unclear, laparoscopy provides significant diagnostic advantages.

Differential Diagnosis

A variety of acute abdominal conditions present symptoms and signs similar to acute appendicitis. Additionally, approximately 20% of appendicitis cases are atypical, necessitating careful differentiation. Accurate diagnosis of acute appendicitis involves avoiding both delays in treatment and misdiagnosis. Differentiation becomes particularly challenging when perforated appendicitis leads to diffuse peritonitis. In some cases, diagnosis can only be confirmed through laparoscopic exploration or exploratory laparotomy.

The following conditions commonly require differentiation from acute appendicitis:

Perforated Gastric or Duodenal Ulcer

Leakage of gastric contents into the abdominal cavity can flow along the paracolic gutter to the right lower quadrant (RLQ), mimicking the migratory pain typical of acute appendicitis. Patients often have a history of peptic ulcer disease and present with sudden, severe abdominal pain. In addition to RLQ tenderness, pain and tenderness are prominent in the upper abdomen, accompanied by significant peritoneal irritation signs such as board-like abdominal rigidity. Chest or abdominal X-rays or CT scans revealing free air under the diaphragm aid in the diagnosis.

Right Ureteral Calculus

This condition often presents as sudden-onset, intermittent, severe colicky pain in the RLQ, radiating to the perineum or external genitalia. RLQ tenderness is usually absent or only mildly present along the course of the ureter with deep palpation. A urinalysis may reveal a significant number of red blood cells. Ultrasound or X-ray imaging may show echogenic foci or shadows at the location of the ureteral stone.

Gynecologic Conditions

Particular attention is required in women of reproductive age.

Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy presents with sudden-onset lower abdominal pain, often accompanied by signs of acute hemorrhage and intra-abdominal bleeding. There may be a history of missed menstrual periods and irregular vaginal bleeding. Physical examination findings include cervical motion tenderness, adnexal masses, and non-clotting blood obtained through posterior fornix culdocentesis.

Ruptured Ovarian Follicular or Corpus Luteum Cysts manifest clinical features similar to ectopic pregnancy but are generally milder. Symptoms often occur around ovulation or after the mid-menstrual phase.

Acute Salpingitis and Acute Pelvic Inflammatory Disease are characterized by gradually increasing lower abdominal pain, sometimes accompanied by lower back pain. Tenderness is usually localized to the lower abdomen, and rectal examination shows symmetrical pelvic tenderness. Fever, elevated white blood cell counts, purulent vaginal discharge, and positive bacterial findings on smear examination support the diagnosis. Culdocentesis may reveal purulent fluid.

Torsion of an Ovarian Cyst Pedicle presents with markedly acute and severe abdominal pain. Pelvic or abdominal examination may reveal a palpable, tender mass. Ultrasound imaging can confirm or exclude these conditions.

Acute Mesenteric Lymphadenitis

This condition is more commonly observed in children and is often preceded by a history of upper respiratory tract infection. Tenderness is typically located more medially in the abdomen, with a less defined and broader distribution that may shift with changes in position. Ultrasound or CT may show enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, which assists in differentiation.

Other Conditions

Acute Gastroenteritis involves prominent symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, without localized RLQ tenderness or peritoneal irritation signs.

Infectious Biliary Tract Diseases can mimic high-position appendicitis but are characterized by severe colic, high fever, and sometimes jaundice. Patients often have a history of recurrent right upper quadrant pain.

Right-Sided Pneumonia or Pleuritis can cause referred pain to the RLQ but is accompanied by respiratory symptoms and signs.

Other conditions requiring differentiation include ileocecal tumors, Crohn’s disease, Meckel’s diverticulitis or perforation, and conditions more common in children, such as intussusception.

Each of these conditions has its distinct characteristics, necessitating careful examination and evaluation. In cases where persistent RLQ pain cannot be explained by other diagnoses, close monitoring or timely surgical exploration may be warranted to rule out acute appendicitis.

Treatment

Surgical Treatment

For the majority of cases of acute appendicitis, once the diagnosis is confirmed, early appendectomy is recommended. Early surgery refers to the removal of the appendix when the inflammation is still limited to luminal obstruction or congestion and edema, making the procedure relatively simple with fewer postoperative complications. Delaying surgery until after suppuration, gangrene, or perforation occurs increases operative complexity and significantly raises the risk of postoperative complications. Preoperative administration of antibiotics helps reduce the risk of postoperative infection.

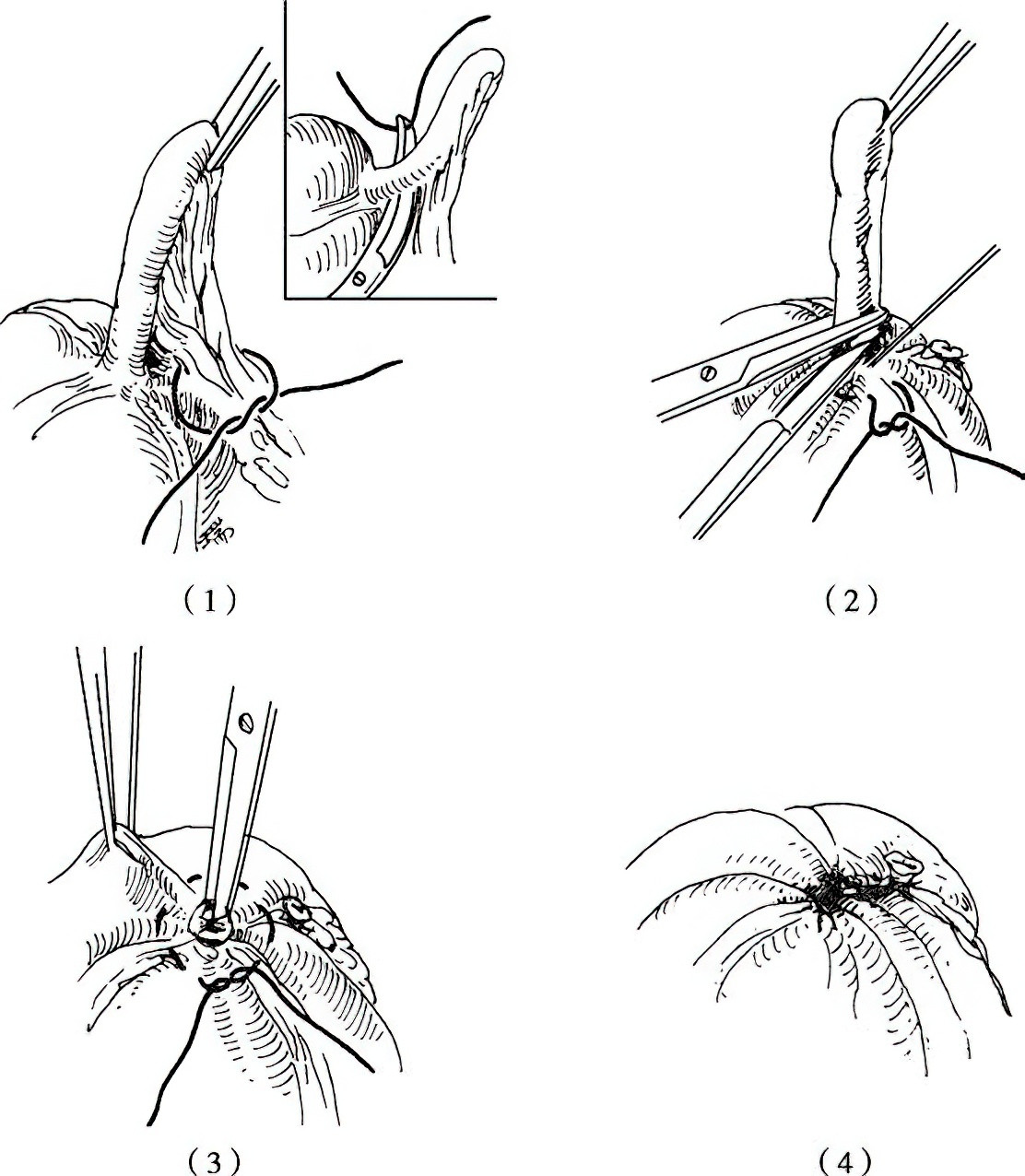

Figure 2 Schematic diagram of appendectomy

(1) Ligation of the mesoappendix.

(2) Transection of the mesoappendix and placement of a purse-string suture.

(3) Removal of the appendix and inversion of the appendiceal stump.

(4) Tightening and ligation of the purse-string suture.

Technical Essentials for Open Appendectomy

Anesthesia: Epidural anesthesia, intravenous general anesthesia, or local infiltration anesthesia can be selected.

Incision Selection

The McBurney incision or transverse incision in the right lower quadrant (RLQ) is commonly used. In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or peritonitis is widespread, a right lower quadrant paramedian incision traversing the rectus abdominis may be required for additional exploration and drainage. Measures should be taken to prevent contamination of the incision.

Locating the Appendix

The appendix is often readily exposed under the incision for some patients. It can typically be found by following the taenia coli on the cecum to the convergence point. If the appendix remains elusive, considerations should be made for a retrocecal position. Palpation behind the cecum or lifting the cecum medially by incising the lateral peritoneum may reveal the appendix.

Management of the Mesentery

The mesoappendix should be elevated using an instrument, such as an appendix clamp, avoiding direct clamping of the appendix itself. If the mesoappendix is thin, it can be ligated in a single bundle with vascular clamps and sutures, ensuring inclusion of the appendiceal vessels before transection. For a thick or wide mesoappendix, progressive clamping, cutting, and ligation are recommended. Secure ligation of the mesoappendix is essential.

Management of the Appendiceal Base

The base of the appendix should be ligated using silk suture or gut suture approximately 0.5 cm from its origin at the cecum. The appendix is then transected 0.5 cm distal to the suture, and the stump is treated with povidone-iodine. A purse-string suture should then be placed on the cecal wall to invert and bury the appendiceal stump. Key points for the purse-string suture include placing it approximately 1 cm from the ligature at the appendiceal base, avoiding inclusion of the mesoappendix, and maintaining a suture distance of 2–3 mm on the taenia coli. Overly extensive inverting sutures should be avoided to prevent formation of a dead space. Alternatively, an "8-shaped" suture can be used to bury the stump and close the appendiceal base simultaneously. Finally, the mesoappendix may be tied down and reinforced over the stump without tension. Recent studies have also supported simple ligature of the appendiceal base without purse-string sutures.

Technical Essentials for Laparoscopic Appendectomy

Anesthesia

Intravenous general anesthesia is used.

Positioning and Trocar Insertion

A laparoscope is introduced through an umbilical port, and additional ports are inserted based on surgeon preference on the left and right sides of the abdomen. Pneumoperitoneum pressure is maintained at approximately 12 mmHg, and the Trendelenburg position combined with left-side tilt enhances visualization of the appendix.

Exploration of the Abdomen and Identification of the Appendix

The abdominal cavity is systematically examined in the following order: liver and gallbladder, stomach, duodenum, colon, spleen, diaphragm, small intestine, appendix, and inguinal inner ring area. For female patients, the uterus and adnexa should also be inspected. The appendix is typically identified by following the taenia coli of the cecum. If the appendix appears normal, further attention should be directed toward identifying other potential causes of abdominal pain.

Management of the Mesentery

Various options are available for handling the mesoappendix and should be selected based on the surgeon's preference and situation. These include:

- Piercing the base of the mesoappendix near the appendiceal attachment and ligating with sutures or using a vascular clamp prior to transection.

- Direct sectioning of the mesoappendix and appendiceal artery with an ultrasonic scalpel.

- Utilizing a linear stapler to simultaneously cut and close the mesoappendix.

- Using bipolar electrocoagulation to dissect the mesoappendix close to the appendix.

Management of the Appendiceal Base

After addressing the mesoappendix, the appendix is elevated, and a vascular clamp is applied to the base of the appendix. Another clamp is positioned 1 cm proximal to the first. The appendix is then transected between the two clamps. The mucosal surface of the appendiceal stump is cauterized using electrosurgery, without the need for stump burial. Alternatively, the stump can be buried with absorbable purse-string sutures or an "8-shaped" suture, but these techniques require higher technical proficiency. Additional options include ligating the base of the appendix with silk sutures or using a linear stapler to simultaneously transect and seal the appendiceal base.

Non-Surgical Management

This approach is only suitable in certain circumstances, including cases of simple appendicitis or early-stage acute appendicitis, where appropriate medical treatment may lead to recovery. Non-surgical management may also be considered for patients who decline surgery, have poor general health, or face contraindications to surgery due to severe coexisting organic diseases or other limiting conditions. The primary measures involve the administration of effective antibiotics and fluid resuscitation. Antibiotics should be selected to provide coverage for both aerobic and anaerobic intestinal flora.

Complications and Their Management

Complications of Acute Appendicitis

Intra-Abdominal Abscess

This is a consequence of untreated appendicitis. The most common type is a peri-appendiceal abscess, but abscesses may also form in other parts of the abdominal cavity, such as the pelvic cavity, subphrenic space, or interintestinal spaces. Clinical manifestations include abdominal distension, symptoms of paralytic ileus, palpable tender masses, and signs of systemic infection and toxemia. Ultrasound and CT scans can assist with localization. Once diagnosed, treatment may involve percutaneous aspiration, irrigation, and drainage under ultrasound guidance, or surgical incision and drainage if necessary. Adhesions caused by inflammation tend to be significant, and care is needed during incision and drainage to avoid collateral damage, particularly to prevent injury to the bowel. The recurrence rate is high following non-surgical treatment of appendiceal abscesses, so an elective appendectomy is generally performed approximately three months after recovery, yielding better outcomes compared to emergency surgery.

Formation of Internal or External Fistulas

If a peri-appendiceal abscess is not promptly drained, there is a risk in rare cases that it may perforate into the small intestine, large intestine, bladder, vagina, or abdominal wall, leading to the formation of internal or external fistulas. Pus may drain through the fistula. X-ray studies with barium contrast or fistulography through external fistulas can help delineate the fistula pathway and inform the selection of appropriate treatment strategies.

Suppurative Portal Vein Thrombophlebitis (Pylephlebitis)

In cases of acute appendicitis, infectious thrombi in the appendicular veins may spread through the superior mesenteric vein to the portal vein, resulting in suppurative portal vein thrombophlebitis. Clinical symptoms include chills, high fever, hepatomegaly, epigastric tenderness, and mild jaundice. Although rare, progression to infectious shock and sepsis may occur if the condition worsens, and delayed treatment can lead to bacterial liver abscesses. Appendectomy combined with high-dose antibiotic therapy is effective in managing this condition.

Postoperative Complications of Appendectomy

Bleeding

Bleeding may occur due to loosening of the ligature around the appendiceal mesentery, leading to hemorrhage from the mesenteric vessels. Symptoms include abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and signs of hypovolemic shock. Prevention is key and includes ensuring secure ligation of the mesoappendix, employing segmental ligation for a thick mesoappendix, maintaining an adequate distance between the ligature and the cut edge of the mesoappendix, and avoiding retraction of the ligature to prevent loosening. In cases of bleeding, blood transfusion and fluid resuscitation are required, followed by emergency reoperation for hemostasis. During laparoscopic appendectomy, precise ligation of the appendiceal artery and proper use of vascular clamps are critical, with segmental ligation recommended for edematous or thick mesoappendices to prevent clip dislodgement or vessel rupture.

Incision Infection

Incision infection is the most common postoperative complication, particularly in cases of suppurative or perforated acute appendicitis. However, advances in surgical techniques and the application of effective antibiotics have reduced its prevalence. Preventive measures include careful protection and irrigation of the incision during surgery, thorough hemostasis, and elimination of dead spaces. Clinical signs of incision infection typically become evident 2–3 days postoperatively and include fever, local swelling, tenderness, and redness around the incision. Treatment involves needle aspiration of pus or removal of sutures at fluctuant sites to allow drainage, along with regular dressing changes. Recovery is typically achieved within a short period.

Adhesive Bowel Obstruction

This is a relatively common complication following appendectomy, often associated with severe local inflammation, surgical trauma, foreign material at the incision, or prolonged postoperative bed rest. Early surgery for acute appendicitis and early mobilization after surgery may help reduce the risk of adhesive bowel obstruction. Severe cases of adhesive bowel obstruction require surgical intervention.

Appendiceal Stump Inflammation

Inflammation of the appendiceal stump may occur if the residual appendix measures longer than 1 cm or if there is retained fecalith, leading to recurrent symptoms resembling appendicitis. In rare cases, the diseased appendix may be mistakenly left in situ and cause postoperative inflammation. Diagnosis can be confirmed with a barium enema and X-ray. For severe symptoms, a second operation to remove the appendiceal stump is necessary.

Fecal Fistula

This is an uncommon complication. Postoperative fecal fistulas may occur due to factors such as simple ligation of the appendiceal stump with subsequent ligature detachment, underlying conditions like primary tuberculosis or carcinoma of the cecum, or fragile edematous cecal tissue resulting in tearing during suturing. If the fecal fistula becomes localized without causing diffuse peritonitis, clinical manifestations are similar to those of peri-appendiceal abscesses. In the absence of conditions like tuberculosis or malignancy, non-surgical management often leads to spontaneous closure of the fistula.