Congenital malrotation of the intestine refers to a developmental anomaly during embryogenesis where abnormal intestinal rotation and fixation lead to the formation of abnormal fibrous bands or shortening of the mesenteric root, causing intestinal obstruction or volvulus.

Etiology and Pathology

During embryonic development, the intestines rotate counterclockwise around the axis of the superior mesenteric artery, moving from left to right. When this normal rotation is complete, the ascending and descending colon are fixed to the posterior abdominal wall via their mesentery. The cecum descends to the right iliac fossa, and the small intestinal mesentery attaches obliquely from the ligament of Treitz on the upper left to the lower right of the posterior abdominal wall.

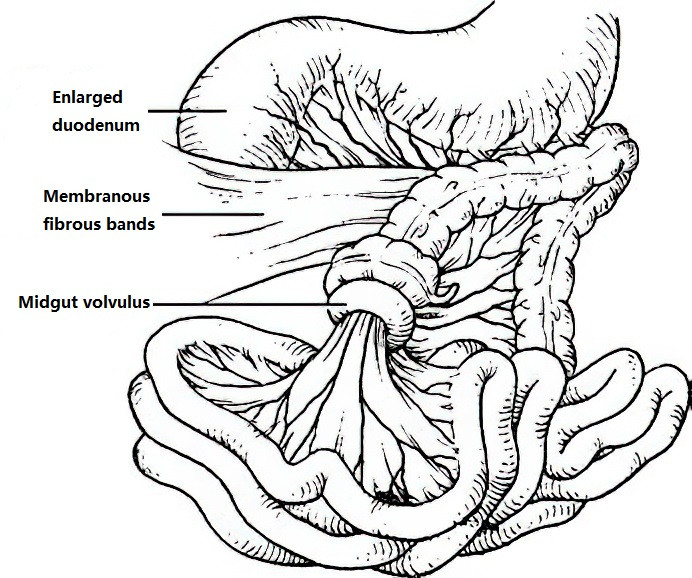

Figure 1 Midgut volvulus (twisting in the clockwise direction)

Abnormalities or arrest at any stage of this rotation process can result in intestinal malrotation. In cases of incomplete rotation, the cecum may be located in the upper abdomen or on the left side. Fibrous bands attaching the posterior abdominal wall to the cecum can compress the duodenum, leading to obstruction. Furthermore, because the small intestine is suspended by a narrow mesenteric root around the superior mesenteric artery, it has greater mobility and is more prone to volvulus, with the mesenteric artery serving as the torsion axis. Severe twisting may compromise mesenteric blood flow, potentially resulting in extensive small bowel necrosis.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical presentation is variable, and the age of onset is unpredictable, with most cases occurring during the neonatal period. A typical symptom is the passage of normal meconium after birth followed by intermittent vomiting 3 to 5 days later. Vomitus often contains bile. Duodenal obstruction in such cases is often incomplete, leading to upper abdominal distension, which may sometimes reveal visible gastric peristaltic waves that resolve after forceful vomiting. Obstruction symptoms tend to recur intermittently, varying in intensity. Affected infants may experience emaciation, dehydration, and weight loss.

In cases of volvulus, the predominant symptoms include frequent vomiting accompanied by persistent abdominal pain. Mild volvulus may resolve on its own with position changes, but worsening volvulus or intestinal necrosis is associated with generalized abdominal distension, diffuse tenderness, muscle rigidity, hematochezia, and severe systemic toxicity or shock.

Diagnosis

Intermittent symptoms of high intestinal obstruction in neonates warrant consideration of intestinal malrotation. Abdominal X-rays may reveal a "double bubble" or "triple bubble" sign. Barium enema X-rays can show displacement of the cecum to the upper abdomen or to the left side. Enhanced abdominal CT may reveal abnormal positioning of the superior mesenteric artery and vein.

Treatment

When significant signs of intestinal obstruction are present, treatment involves fluid resuscitation, correction of electrolyte imbalances, and gastrointestinal decompression before surgical intervention.

The surgical approach involves relieving the obstruction and restoring intestinal continuity. Depending on the specific circumstances, procedures may include cutting the peritoneal bands compressing the duodenum, mobilizing the adhesions in the duodenum, or releasing the cecum. In cases of volvulus, derotation of the intestinal loops is performed. For intestinal necrosis, bowel resection and subsequent anastomosis are necessary.