Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), also known as gastroesophageal airway reflux disease, refers to a condition characterized by discomfort symptoms, end-organ effects, and/or complications caused by the irritation and damage to the esophagus, airways, and other reflux pathways from digestive reflux materials. The prevalence of GERD is approximately 10%, with the condition being more common among middle-aged and elderly populations.

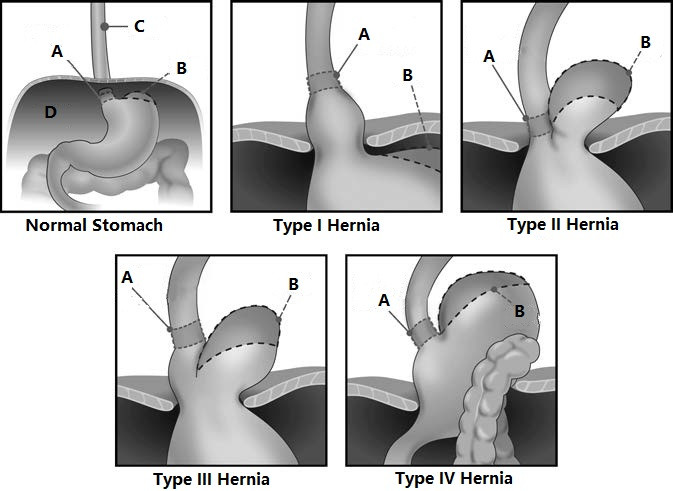

Figure 1 Normal stomach and types I to IV of hiatal hernia (Type I accounting for approximately 95%)

A, Gastroesophageal junction

B, Gastric fundus

C, Esophagus

D, Diaphragm

GERD typically results from factors such as hiatal hernia, lower esophageal sphincter relaxation, decreased gastrointestinal motility, and hypersensitivity of the esophagus and airways. Symptoms related to GERD vary significantly among individuals. Typical symptoms include heartburn and regurgitation, while atypical symptoms include chest or back pain, belching, and vomiting. Extra-esophageal symptoms, such as cough, breathing difficulties (e.g., dyspnea, wheezing, and choking), pharyngitis (e.g., a sensation of a foreign body in the throat), rhinitis (e.g., postnasal drip), and oral disorders (e.g., dental erosion), are also common. Due to the non-specific nature of atypical and extra-esophageal symptoms, misdiagnosis is frequent. Complications of GERD include reflux esophagitis (accounting for 10%–30% of GERD cases), Barrett's esophagus, and even esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Diagnosis

GERD may be considered when mild symptoms occur at least 2 days per week or when moderate to severe symptoms occur at least 1 day per week for a duration of 8 weeks or more, or when complications such as reflux esophagitis are clearly detected. Objective diagnostic tests for GERD include gastroscopy, reflux monitoring, high-resolution manometry, upper gastrointestinal barium studies, and CT imaging. Findings such as reflux esophagitis, lower esophageal sphincter relaxation, hiatal hernia, abnormal esophageal reflux exposure (particularly abnormal esophageal acid exposure), a positive correlation between reflux and symptoms, and a positive response to acid suppression therapy support the diagnosis of GERD. These findings also provide essential information for evaluating surgical options.

Treatment

More than 70% of GERD patients achieve satisfactory outcomes with acid suppression and other medical therapies, though over 50% require chronic disease management. Approximately 30%–35% require long-term medications, fail to achieve adequate symptom control, or present with complications and/or hiatal hernia, leading to significant declines in quality of life or disease progression, warranting surgical intervention. Laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair combined with fundoplication is effective in restoring and enhancing anti-reflux structures and functions, providing durable control of most forms of reflux. The goals of surgery include symptom relief, improvement in quality of life, prevention or resolution of complications, and avoidance of long-term medication use.

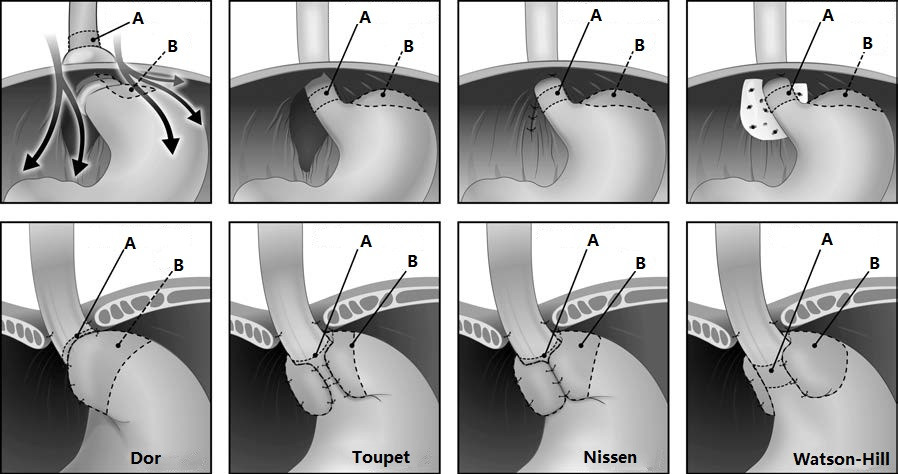

Figure 2 Laparoscopic Hiatal Hernia Repair and Four Types of Fundoplication

A, Gastroesophageal junction

B, Gastric fundus

Indications for Surgery:

- Failure of medical therapy (insufficient symptom control, persistent reflux despite acid suppression, or inability to continue medication due to side effects);

- Patient preference for surgery despite effective long-term medical therapy (considerations include quality of life, lifelong medication use, and cost of treatment);

- Severe complications of GERD, such as advanced reflux esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, or inflammatory esophageal strictures;

- Chronic GERD associated with hiatal hernia (hiatal hernia as a cause of chronic GERD and/or acute gastrointestinal obstruction symptoms);

- Manifestations of chronic extra-esophageal symptoms, such as cough, asthma, reflux-induced laryngitis, laryngospasm, or pulmonary fibrosis.