Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors, with a higher incidence in individuals over 50 years of age.

Etiology

The exact causes of gastric cancer remain unclear, but its development is associated with the following factors:

Geographical and Environmental Factors

The incidence of gastric cancer exhibits distinct geographical variability. Globally, Japan has the highest incidence rate, while the United States has a relatively lower rate.

Dietary and Lifestyle Factors

Populations that frequently consume smoked or salted foods have a higher risk of gastric cancer, which is linked to high levels of carcinogens such as nitrosamines, fungal toxins, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in these foods. The risk of gastric cancer is also 50% higher in smokers compared to non-smokers.

Helicobacter pylori Infection

Individuals positive for Helicobacter pylori (HP) have a 3 to 6 times higher risk of developing gastric cancer compared to those who are HP-negative. Controlling HP infection has increasingly been recognized as critical in the prevention and treatment of gastric cancer.

Chronic Diseases and Precancerous Lesions

Certain gastric diseases are prone to the development of gastric cancer, including gastric polyps, chronic atrophic gastritis, and the remnant stomach after partial gastrectomy. Gastric polyps can be classified into inflammatory polyps, hyperplastic polyps, and adenomas. The risk of malignant transformation is low in the first two types, while gastric adenomas carry a cancer risk of 10%–20%, with a greater probability of malignancy when their diameter exceeds 2 cm. Atrophic gastritis is characterized by the atrophy and reduction of gastric mucosal glands, frequently accompanied by intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia, which may progress to cancer. Chronic inflammatory changes in the mucosa of the remnant stomach may lead to gastric stump cancer 15–25 years after partial gastrectomy. Precancerous lesions refer to pathological histological changes in the gastric mucosa that are predisposed to malignancy but are not inherently malignant. These represent pathological stages in the transition from benign epithelial tissue to malignancy. Dysplasia of the gastric mucosal epithelium can be classified into mild, moderate, and severe varieties based on the degree of cellular atypia, with severe dysplasia being difficult to distinguish from early well-differentiated gastric cancer.

Heredity and Genetics

Individuals with a family history of gastric cancer have a fourfold higher incidence compared to control groups, indicating a role for genetic factors.

Pathology

Macroscopic Types

Early Gastric Cancer

This refers to lesions confined to the mucosa or submucosa. Based on morphological appearance, early gastric cancer is classified into three main types:

- Type I: Elevated type, with the lesion projecting into the gastric cavity.

- Type II: Superficial type, characterized by flat lesions without significant elevations or depressions. Type II is further subdivided into IIa (superficial elevated type), IIb (superficial flat type), and IIc (superficial depressed type).

- Type III: Depressed type, appearing as a deeper ulcerated area.

Advanced Gastric Cancer

This encompasses cancers infiltrating deeper than the submucosa. The Borrmann classification divides advanced gastric cancer into four types:

- Type I (Polypoid Type): A well-demarcated nodular lesion protruding into the gastric cavity.

- Type II (Ulcerated, Localized Type): A well-defined ulcerative lesion with slightly raised edges.

- Type III (Ulcerated, Infiltrative Type): An ulcer with poorly defined borders and surrounding tissue infiltration.

- Type IV (Diffuse Infiltrative Type): A lesion that diffusely infiltrates all layers of the gastric wall, leading to indistinct borders. When the entire stomach is involved, resulting in a narrowed lumen and a rigid, leather-bag-like appearance, it is referred to as "linitis plastica," which is associated with a poor prognosis.

The most common site of gastric cancer is the gastric antrum, accounting for approximately half of all cases. The gastric fundus and cardia are the second most common sites, comprising about one-third of cases.

Histological Types

The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System (2019) identifies five common subtypes of gastric cancer:

- Tubular adenocarcinoma

- Papillary adenocarcinoma

- Poorly cohesive carcinoma (including signet-ring cell carcinoma and other types)

- Mucinous adenocarcinoma

- Mixed adenocarcinoma

It also recognizes five rarer subtypes:

- Carcinoma with lymphoid stroma

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma

- Adenocarcinoma with enteroblastic differentiation

- Fundic gland carcinoma

- Micropapillary adenocarcinoma

The majority of gastric cancers are adenocarcinomas.

Spread and Metastasis

Direct Infiltration

Infiltrative gastric cancer that penetrates the serosa is prone to spreading to neighboring organs such as the omentum, colon, liver, spleen, and pancreas. Once the cancer invades the submucosa, it may spread through tissue gaps and lymphatic networks. For cancers located at the gastric fundus and cardia, the lower esophagus is commonly affected. For cancers in the gastric antrum, infiltration into the duodenum often occurs, typically limited to within 3 cm below the pylorus.

Lymphatic Metastasis

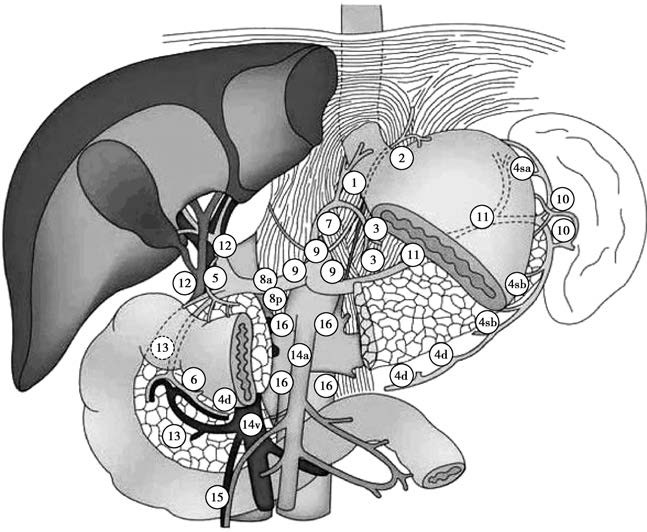

Lymphatic metastasis is the primary pathway for gastric cancer dissemination. The lymphatic metastasis rate reaches nearly 20% in early-stage gastric cancer and approximately 70% in advanced gastric cancer. In most cases, metastasis follows the direction of lymphatic drainage, though skip metastasis occurs in some cases. Regional lymph nodes of the stomach are divided into 23 groups:

- Group 1: Right cardia region

- Group 2: Left cardia region

- Group 3: Along the lesser curvature

- Group 4sa: Along short gastric vessels

- Group 4sb: Along the left omental vessels

- Group 4d: Along the right omental vessels

- Group 5: Upper pyloric region

- Group 6: Lower pyloric region

- Group 7: Along the left gastric artery

- Group 8a: Anterior to the common hepatic artery

- Group 8p: Posterior to the common hepatic artery

- Group 9: Along the celiac artery

- Group 10: At the splenic hilum

- Group 11p: Proximal portion of the splenic artery

- Group 11d: Distal portion of the splenic artery

- Group 12a: Along the hepatic artery

- Group 12p: Behind the portal vein

- Group 12b: Along the common bile duct

- Group 13: Behind the pancreatic head

- Group 14v: Along the superior mesenteric vein

- Group 14a: Along the superior mesenteric artery

- Group 15: Along the middle colic vessels

- Group 16: Along the abdominal aorta

- A1: From the aortic hiatus to the upper margin of the celiac trunk

- A2: From the upper margin of the celiac trunk to the lower margin of the left renal vein

- B1: From the lower margin of the left renal vein to the upper margin of the inferior mesenteric artery

- B2: From the upper margin of the inferior mesenteric artery to the aortic bifurcation

- Group 17: Anterior to the pancreatic head

- Group 18: Along the inferior pancreatic margin

- Group 19: Subdiaphragmatic region

- Group 20: Around the esophageal hiatus

- Group 110: Along the distal thoracic esophagus

- Group 111: Supradiaphragmatic region

- Group 112: In the posterior mediastinum

Figure 1 Illustration of lymph node grouping in the stomach

Two additional lymph node groups hold significant clinical relevance. Enlargement of the left supraclavicular lymph nodes (Virchow's nodes) indicates the spread of cancer via the thoracic duct, while periumbilical lymph node enlargement suggests dissemination through the lymphatic vessels within the round ligament of the liver.

Hematogenous Metastasis

Gastric cancer cells enter the portal or systemic circulation, spreading to distant organs and forming metastatic foci. The liver, lungs, pancreas, and bones are common sites of metastasis, with the liver being the most frequently affected.

Peritoneal Seeding

Gastric cancer that invades beyond the serosa may shed tumor cells, which implant on the peritoneum and visceral serosa, forming metastatic nodules. Metastatic cancer in the rectouterine pouch (Douglas' pouch) can be detected via a rectal exam. In women, gastric cancer may metastasize to the ovaries, forming Krukenberg tumors. Widespread peritoneal dissemination of cancer cells can result in significant malignant ascites.

Clinical and Pathological Staging

The TNM staging system, established by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), is based on tumor infiltration depth, lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis.

T (Tumor): Represents the depth of the primary tumor's invasion of the stomach wall.

Tx: Primary tumor cannot be assessed.

T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

Tis: Carcinoma in situ; intraepithelial tumor without invasion of the lamina propria, characterized by high-grade dysplasia.

T1: Tumor invades the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa.

T1a: Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae.

T1b: Tumor invades the submucosa.

T2: Tumor invades the muscularis propria.

T3: Tumor penetrates through the subserosal connective tissue without infiltration of the visceral peritoneum or adjacent structures.

T4: Tumor invades the serosa (visceral peritoneum) or adjacent structures.

T4a: Tumor invades the serosa.

T4b: Tumor invades adjacent structures.

N (Node): Represents regional lymph node metastasis.

Nx: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed.

N0: No regional lymph node metastasis.

N1: Metastasis in 1–2 regional lymph nodes.

N2: Metastasis in 3–6 regional lymph nodes.

N3: Metastasis in 7 or more regional lymph nodes.

N3a: Metastasis in 7–15 regional lymph nodes.

N3b: Metastasis in 16 or more regional lymph nodes.

M (Metastasis): Represents distant metastasis.

M0: No distant metastasis.

M1: Presence of distant metastasis.

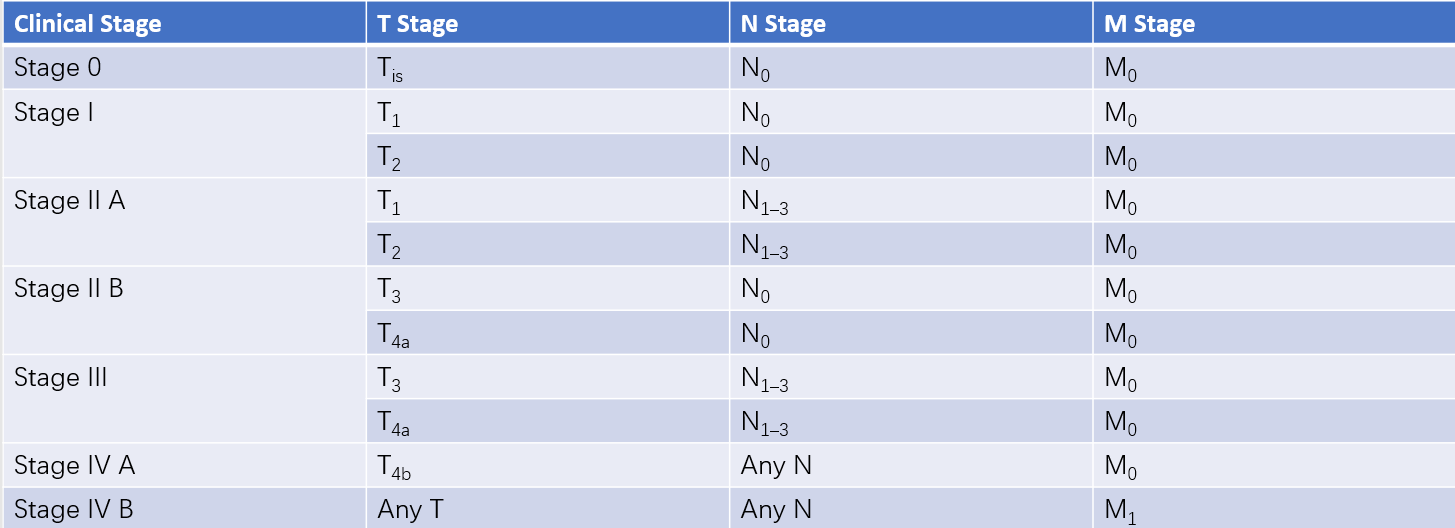

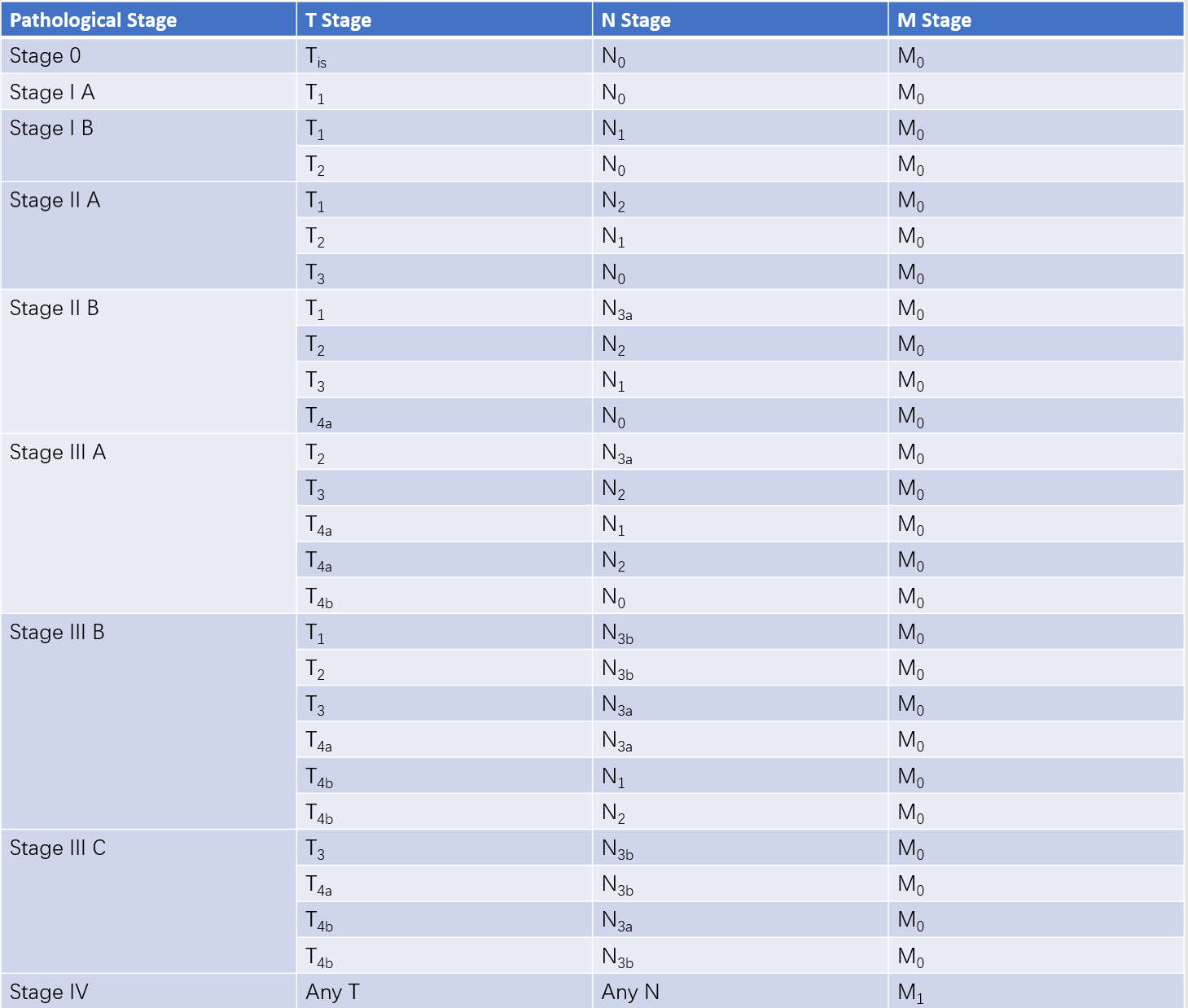

Different combinations of TNM stages categorize gastric cancer into clinical and pathological stages I to IV.

Table 1 Clinical staging of gastric cancer (cTNM)

Table 2 Pathological staging of gastric cancer (pTNM)

Clinical Features

Most patients with early-stage gastric cancer are asymptomatic or present with non-specific symptoms such as epigastric discomfort, postprandial fullness, or nausea. Gastric antrum cancer frequently presents with symptoms resembling duodenal ulcers. A portion of patients who are initially treated for chronic gastritis or duodenal ulcers may experience temporary symptom relief, which can lead to delayed diagnosis. As the disease progresses, symptoms such as worsening epigastric pain, loss of appetite, fatigue, weight loss, and cachexia develop.

Specific symptoms may vary according to tumor location. Cancers in the cardia or fundus may be associated with retrosternal pain and a sensation of food obstruction. Advanced tumors near the pylorus can cause partial or total pyloric obstruction, resulting in vomiting of undigested food or gastric fluid. Tumor ulceration or invasion of gastric wall vasculature can lead to gastrointestinal bleeding, manifesting as hematemesis or melena. Acute perforation may also occur.

Early-stage patients generally lack notable physical findings. Advanced-stage disease may present with a palpable, firm, fixed mass in the epigastrium, supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, peritoneal carcinomatosis (e.g., ascites), anemia, jaundice, malnutrition, or even cancerous cachexia.

Diagnosis

The 5-year survival rate for early-stage gastric cancer following surgery exceeds 90%, which is significantly better than for advanced gastric cancer. Early diagnosis is therefore critical for improving the cure rate. To increase the rate of early gastric cancer diagnosis, regular screening should be considered for the following groups:

- Individuals over the age of 40 who develop the aforementioned gastrointestinal symptoms without a history of gastric disease or whose ulcer symptoms and pain patterns have significantly changed compared to their past experiences.

- Individuals with a family history of gastric cancer.

- Individuals with premalignant gastric conditions, such as atrophic gastritis, gastric ulcers, gastric polyps, or a history of partial gastrectomy.

- Individuals with unexplained chronic gastrointestinal bleeding or significant weight loss over a short period.

Various diagnostic methods are available for gastric cancer, including:

Electronic Gastroscopy

Electronic gastroscopy allows for direct observation of the site and extent of gastric mucosal lesions. It enables biopsy of suspicious lesions for pathological examination, making it the most effective diagnostic method for gastric cancer. To improve diagnostic accuracy, multiple tissue samples should be taken from the suspected areas. The detection rate of early and micro-gastric cancers can significantly improve with the use of chromoendoscopy and magnifying endoscopy. Electronic gastroscopy equipped with an ultrasound probe can be used to assess the depth of tumor invasion into the gastric wall and evaluate extramural infiltration, aiding in preoperative clinical staging and determining whether the lesion is amenable to endoscopic resection.

X-ray Barium Meal Examination

Double-contrast imaging, combining gas and barium, is used to diagnose gastric cancer by observing the mucosal and filling phases. The advantages of this method include minimal discomfort and better acceptability for patients. However, it is less intuitive than gastroscopy and does not allow for biopsy sampling. Typical X-ray findings include niche shadows, filling defects, gastric wall rigidity, gastric lumen narrowing, and changes in mucosal folds. Barium meal examination can also help evaluate whether gastric cancer in the upper part of the stomach has invaded the esophagus.

CT Scan

Enhanced spiral CT is highly valuable for assessing the extent of gastric cancer, local lymph node involvement, and distant metastases, such as to the liver or ovaries. It plays an important role in evaluating tumor N staging (lymph node metastasis) and M staging (distant metastasis) prior to surgery.

Other Imaging Examinations

MRI has a role similar to that of CT scans. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) can assist in the diagnosis of gastric cancer, particularly for determining lymph node involvement and distant metastases.

Other Tests

Occult blood in the stool may be persistently positive in some gastric cancer patients. Tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA19-9, and CA125 may be elevated in some patients with gastric cancer. However, these markers are currently regarded as indicators of prognosis and therapeutic outcomes, rather than diagnostic tools for gastric cancer.

A correct diagnosis for most gastric cancers can be made based on clinical symptoms, electronic gastroscopy, or imaging studies. In rare cases, differential diagnosis may be needed to distinguish gastric cancer from benign gastric ulcers, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, gastric lymphomas, or other benign gastric tumors.

Treatment

The treatment approach for gastric cancer primarily involves comprehensive strategies centered on surgical intervention. Endoscopic resection is an option for certain cases of early gastric cancer, while adequate gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy are emphasized for advanced gastric cancer. Comprehensive treatments, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, are commonly used for patients with unresectable tumors or postoperative recurrence and may also serve as adjuvant treatments following curative surgery.

Endoscopic Treatment for Early Gastric Cancer

For differentiated mucosal cancers smaller than 2 cm in diameter with no ulceration, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) may be performed. ESD is more frequently recommended in clinical practice, involving circumferential incision of the mucosa around the lesion with a high-frequency electric knife followed by dissection between the submucosal and muscular layers. For early gastric cancers with submucosal invasion, incomplete resection, or possible lymph node metastasis, endoscopic treatment is generally not appropriate, and standard surgical resection is recommended as the preferred approach.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery remains the primary treatment for gastric cancer, categorized into radical and palliative surgeries.

Radical Surgery

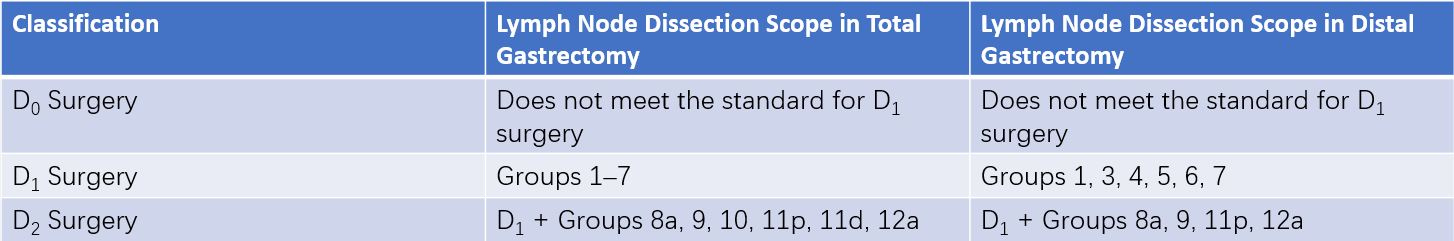

Radical surgery aims to completely resect the primary gastric tumor, systematically clear regional lymph nodes according to clinical staging criteria, and reconstruct the digestive tract. The D2 lymphadenectomy is regarded as the standard surgical procedure for radical gastrectomy in gastric cancer.

Gastrectomy types and resection scopes:

- Total Gastrectomy: Removal of the entire stomach, including the cardia and pylorus.

- Distal Gastrectomy: Removal of the distal portion of the stomach, including the pylorus, while preserving the cardia. The standard extent involves resecting at least two-thirds of the stomach.

- Proximal Gastrectomy: Removal of the proximal portion of the stomach, including the cardia, while preserving the pylorus.

Resection margins are required to extend at least 5 cm beyond the tumor edge. For distal gastric cancers, the duodenal bulb should also be resected by 3–4 cm. For proximal cancers, 3–4 cm of the lower esophagus should be removed. Resected margins must be negative for residual tumor.

The extent of lymph node dissection is classified using the D (dissection) standard based on the type of gastrectomy performed. Lymphadenectomy is categorized into D1 and D2 levels.

- D1 dissection is applicable only for clinical T1N0 early gastric cancers unsuitable for endoscopic treatment.

- D2 dissection is required for advanced gastric cancers (T2–T4 tumors and those with clinical lymph node involvement). Since precise assessment of lymph node metastasis is often unreliable preoperatively or intraoperatively, D2 lymphadenectomy is recommended when lymph node metastasis is suspected.

Table 3 Lymphadenectomy scope in radical gastrectomy

Examples of surgical procedures:

- Radical Distal Gastrectomy: Removal of three-quarters to four-fifths of the stomach with duodenal transection 3–4 cm below the pylorus and gastric transection 5 cm from the tumor edge. Lymph nodes are dissected according to D2 standards, and the greater omentum and omental bursa are excised. Digestive tract reconstruction may involve either Billroth I (gastroduodenostomy) or Billroth II (gastrojejunostomy).

- Radical Total Gastrectomy: Often indicated for cancers in the gastric body or upper stomach. This procedure involves complete stomach removal, duodenal transection 3–4 cm below the pylorus, and esophageal transection 3–4 cm above the esophagogastric junction. Lymph nodes are dissected according to D2 standards, with the greater omentum, omental bursa, and occasionally the spleen removed as needed. Digestive tract reconstruction typically employs esophagojejunostomy using the Roux-en-Y technique.

- Laparoscopic Radical Gastrectomy: Laparoscopic approaches for gastric cancer have been increasingly adopted in clinical practice. Prospective randomized controlled trials have shown that for clinical stage I cancers, laparoscopic surgery is comparable to open surgery in terms of safety and therapeutic outcomes and can be used as a standard procedure. For advanced gastric cancers beyond stage I, laparoscopic surgery has shown comparable safety profiles to open surgery, but long-term outcomes require further validation.

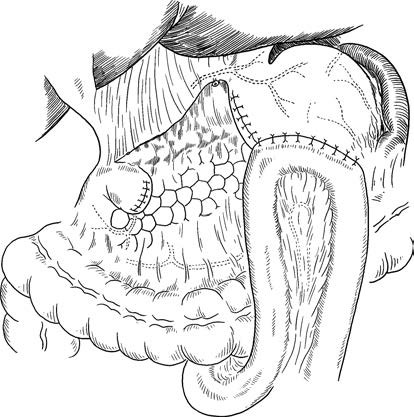

Figure 2 Radical distal gastrectomy with Billroth II gastrojejunostomy

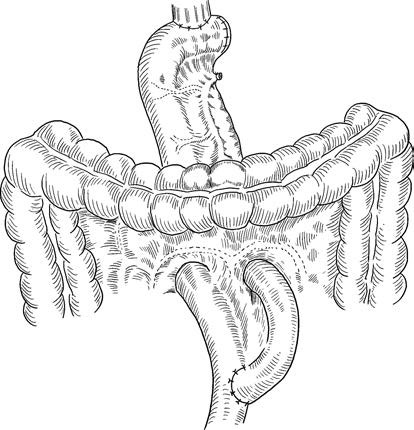

Figure 3 Radical total gastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy using Roux-en-Y reconstruction

Palliative Surgery

Palliative surgery is intended for cases where the primary tumor cannot be completely resected and aims to address complications caused by gastric cancer, such as obstruction, perforation, or bleeding. Procedures include partial gastrectomy, gastrojejunostomy, jejunostomy, or perforation repair.

Chemotherapy for Gastric Cancer

Chemotherapy may slow tumor progression and alleviate symptoms for patients with unresectable, recurrent, or advanced cancer following palliative surgery. Adjuvant chemotherapy after radical surgery aims to eliminate residual tumor cells and reduce the risk of recurrence. Adjuvant chemotherapy is generally not necessary for early gastric cancer following radical surgery. Candidates for chemotherapy should have a confirmed pathological diagnosis, satisfactory overall health, normal cardiac, hepatic, renal, and hematopoietic function, and no severe complications.

Other Treatment Options

Gastric cancer has low sensitivity to radiotherapy, which is rarely employed but can provide some relief for local pain caused by tumors. Immunotherapy options include nonspecific biological response modifiers, cytokines, and adoptive immunotherapy. In recent years, anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies have shown notable efficacy in advanced gastric cancer and have demonstrated some promise in neoadjuvant settings. Targeted therapy options, such as trastuzumab (anti-HER2 antibody), bevacizumab (anti-VEGFR antibody), and cetuximab (anti-EGFR antibody), have demonstrated efficacy in advanced gastric cancer.