In healthy individuals, intra-abdominal pressure is close to atmospheric pressure, approximately 5–7 mmHg. Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) ≥ 12 mmHg is classified as intra-abdominal hypertension, while IAP ≥ 20 mmHg accompanied by organ dysfunction related to elevated abdominal pressure is defined as abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). Factors leading to an increase in abdominal cavity volume or a relative reduction in abdominal cavity compliance can cause elevated IAP. These factors are generally divided into two categories:

- Abdominal Wall Factors: Reduced abdominal wall compliance due to severe abdominal burns with eschar constriction, abdominal wall ischemia and edema, or forced abdominal closure after repair of large abdominal wall hernias.

- Intra-Abdominal Factors: Increased intra-abdominal contents, such as significant intra-abdominal hemorrhage, severe organ edema, gastrointestinal distension, mesenteric vein thrombosis, ascites, or intra-abdominal abscesses. Patients requiring massive fluid resuscitation, such as those with extensive burns or severe pancreatitis, are also at risk for elevated IAP.

Pathophysiology

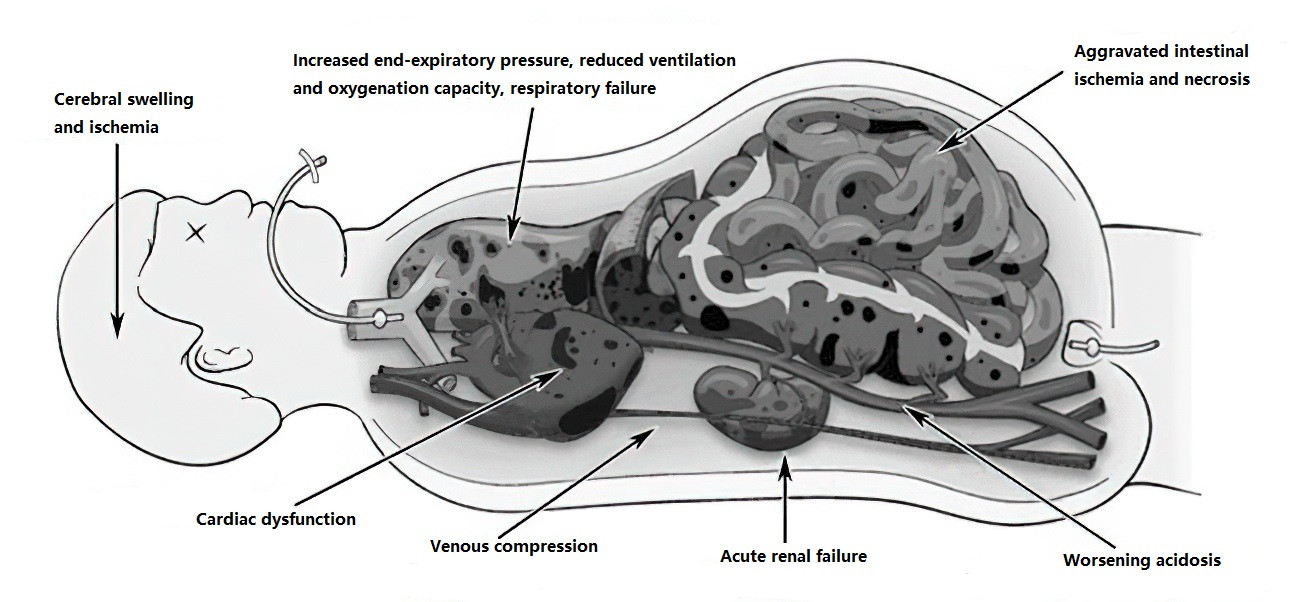

Progressive increases in intra-abdominal pressure compress the inferior vena cava, reduce venous return to the heart, and lead to a decline in blood pressure. Cardiac output decreases due to increased vascular resistance. The elevated abdominal pressures are transmitted to the thoracic cavity, causing diaphragm elevation, increased respiratory and pulmonary vascular resistance, hypoxemia, and hypercapnia. Elevated thoracic pressure may also increase central venous pressure, impairing cerebral venous return. Mesenteric blood flow and portal venous return are reduced, resulting in intestinal and hepatic ischemia. Furthermore, decreased cardiac output and systemic hypotension lead to reduced renal blood flow. Compression of the renal veins causes increased renal venous pressure, a decrease in glomerular filtration rate, and the development of oliguria or anuria.

Figure 1 Pathophysiological features of ACS (Illustration)

Clinical Presentation

Patients may present with chest tightness, shortness of breath, respiratory distress, and tachycardia. Abdominal distension is often observed, sometimes accompanied by abdominal pain and diminished or absent bowel sounds. Early-stage ACS can present with hypercapnia and oliguria. In advanced stages, anuria, azotemia, respiratory failure, and low cardiac output syndrome may occur.

Diagnosis

For suspected ACS, routine monitoring of intra-abdominal pressure is critical. Bladder pressure measurement is the most common diagnostic method due to its simplicity and repeatability. A Foley catheter is inserted through the urethra, and after emptying the bladder, 100 ml of saline is instilled. The catheter is connected to a pressure transducer, and pressure is measured at the pubic symphysis level in the supine position during expiration. In mechanically ventilated patients, temporary cessation of ventilation during the measurement can enhance accuracy.

Imaging studies play an important role in ACS diagnosis. Findings include significant intra-abdominal fluid accumulation, a "round belly" sign, thickened bowel walls, widespread mesenteric swelling and diffuse blurring, collapsed spaces between abdominal organs, and compressed or displaced kidneys. Narrowing of renal vasculature and the inferior vena cava may also be observed.

ACS is diagnosed when IAP reaches ≥ 20 mmHg and is accompanied by organ dysfunction. This stage may include refractory acidosis or multi-organ failure. In the early stages, neuromuscular blockers and other medications can be employed to alleviate abdominal wall tension and reduce intra-abdominal contents. If the condition progresses, suspending enteral nutrition or proceeding with decompressive laparotomy may be necessary to lower the pressure and prevent secondary organ failure caused by elevated IAP.

Treatment

Non-Surgical Treatment

A comprehensive approach is employed, including fluid resuscitation, diuretics, mechanical ventilation with positive pressure, reduction of systemic inflammation, enhancement of organ function, improvement of gastrointestinal emptying, and appropriate nutritional support. Ultrasound or CT-guided percutaneous drainage of ascitic fluid is a minimally invasive and effective method, often involving multipoint punctures with catheter placement for continuous drainage. Throughout non-surgical management, close monitoring is essential to avoid missing the opportunity for surgical intervention.

Surgical Treatment

When non-surgical therapies prove ineffective, and IAP exceeds 25 mmHg, threatening life, decompressive laparotomy becomes necessary. This involves opening the abdomen without closing the muscle and fascial layers after surgery. A vertical midline incision is often used, or a prior abdominal incision is reopened. Hematoma, fluid collections, and tamponades are removed to achieve abdominal decompression. Non-adherent synthetic meshes are applied to cover and protect the abdominal organs. During surgical intervention, care is taken to prevent damage to the abdominal organs, particularly the intestines. Definitive surgery should be performed promptly to address the underlying causes of elevated abdominal pressure and restore the physiological environment of intra-abdominal organs.