Abdominal injury refers to damage occurring in the abdominal region, which is commonly seen in both peacetime and wartime. Its incidence during peacetime is approximately 0.4% to 1.8% of all injuries. Due to the complexity of abdominal organs, with their diverse anatomical and physiological functions, abdominal injury is varied in presentation. Massive bleeding within the abdominal cavity and severe infection are the primary causes of death. The critical factors in reducing mortality include timely and accurate assessment of the presence of visceral injury, intra-abdominal hemorrhage, the type of organ involved (solid or hollow), and the specific organ damaged, along with providing appropriate treatment.

Classification

Based on whether the abdominal wall is penetrated and whether the abdominal cavity is in communication with the external environment, abdominal injuries are classified into open and closed types. Open injuries are considered penetrating if the peritoneum is breached and non-penetrating if it is not. Among open injuries, those caused by projectiles with both an entry and an exit wound are called perforating wounds, while those with only an entry wound are termed blind wounds. In cases of open injuries, even if the viscera are involved, the diagnosis is often relatively clear. Closed injuries may be limited to the abdominal wall or may involve the internal organs. Their diagnosis can be more challenging due to the absence of external wounds on the surface, giving them greater clinical significance. Additionally, injuries caused by diagnostic or therapeutic procedures such as punctures, endoscopic procedures, enemas, uterine curettage, or abdominal surgeries are classified as iatrogenic injuries.

Etiology

Open injuries are often caused by sharp objects such as knives, blades, or bullets, while closed injuries typically result from blunt forces such as falls, collisions, impacts, crushing, or strikes from blunt instruments. Both open and closed injuries can lead to damage to abdominal organs. In open injuries, the most commonly affected organs, in order, are the liver, small intestine, stomach, colon, and major blood vessels. In closed injuries, the frequently injured organs, in order, are the spleen, kidneys, small intestine, liver, and mesentery.

The extent and severity of abdominal injuries largely depend on factors such as the intensity, velocity, location, and direction of the force, as well as intrinsic factors like anatomical features, pre-existing pathological conditions, and the functional state of the organs. For example:

- The liver and spleen, due to their fragile structure, rich blood supply, and fixed position, are prone to rupture when subjected to blunt force.

- When the upper abdomen is compressed, the gastric antrum, horizontal part of the duodenum, or pancreas may be crushed against the spine, leading to rupture.

- Fixed portions of the intestines (e.g., the proximal jejunum, terminal ileum, or adherent bowel loops) are more vulnerable to injury than mobile segments.

- Distended hollow organs (e.g., a stomach after a full meal or a non-emptied bladder) are more susceptible to rupture compared to when they are empty.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of abdominal injury vary greatly depending on the cause and severity of the injury. Isolated abdominal wall injuries generally show mild symptoms and signs, which may include pain at the injury site, subcutaneous bruising, localized swelling, and tenderness of the abdominal wall. If accompanied by visceral contusion, symptoms may be absent or limited to abdominal pain, but severe cases can present with intra-abdominal hemorrhage or peritonitis.

For injuries to solid organs such as the liver, spleen, pancreas, kidneys, or major blood vessels, the primary clinical manifestations include intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal bleeding, with severe cases potentially leading to shock. The pain is typically continuous but not severe, and signs of peritoneal irritation may be minimal. If liver rupture involves disruption of larger intrahepatic bile ducts, or if pancreatic injury involves pancreatic duct rupture, leakage of bile or pancreatic juice can lead to significant abdominal pain and peritoneal irritation, with the physical signs often localized to the area of injury. Referred pain to the shoulder suggests diaphragmatic irritation and is commonly associated with liver or spleen injuries. Subcapsular liver or spleen ruptures, as well as mesentery or omental hematomas, may manifest as abdominal masses. Shifting dullness is considered a strong indicator of intra-abdominal hemorrhage but is only detectable when the volume of bleeding is significant, limiting its utility for early diagnosis. Hematuria may be present in cases of kidney injury.

The primary clinical manifestations of hollow organ rupture, such as those involving the gastrointestinal tract, biliary tract, or bladder, include localized or diffuse peritonitis. In addition to gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, hematochezia, hematemesis) and signs of systemic infection, the most prominent finding is peritoneal irritation, with the severity varying according to the nature of the contents from the hollow organ. Gastric fluid, bile, and pancreatic juice cause the most severe irritation, followed by intestinal fluid, with blood causing the least. Paralytic ileus may occur, leading to abdominal distension, with severe cases potentially resulting in septic shock. Patients with retroperitoneal duodenal rupture may present with symptoms and signs such as testicular pain, scrotal hematoma, or priapism. Additionally, ruptures of hollow organs may involve varying degrees of hemorrhage, but the volume of blood loss is usually not substantial unless there is concurrent injury to nearby major blood vessels.

Diagnosis

A detailed history of trauma and a thorough physical examination form the primary basis for diagnosing abdominal injuries. However, in urgent situations, diagnostic efforts often need to proceed simultaneously with emergency interventions, such as bleeding control, fluid resuscitation, and airway management. Regardless of whether the injury is open or closed, it is essential to exclude associated injuries to other parts of the body (e.g., cranial, thoracic, spinal, or limb fractures) before focusing on determining the presence of visceral injuries, analyzing the nature, location, and severity of these injuries, and establishing indications for exploratory laparotomy.

The diagnosis of open abdominal injuries requires careful evaluation to determine whether a penetrating injury is present. Clear evidence of peritoneal penetration includes peritoneal irritation or visible intra-abdominal tissue or organs protruding through the abdominal wall wound, with most cases also involving visceral injuries. Specific considerations for diagnosing penetrating injuries include the following:

- The entry and exit wounds of penetrating injuries may not always be located in the abdomen but may instead be in the chest, shoulder, waist, buttocks, or perineum.

- Tangential wounds to the abdominal wall that do not penetrate the peritoneum do not rule out the possibility of visceral injury.

- The entry and exit points of a penetration path may not align in a straight line, as the trajectory can be altered by the victim's posture at the time of injury or by the resistance of dense tissues to a projectile with low or reduced velocity.

- The size of the wound does not necessarily correlate with the severity of the underlying injury.

For closed abdominal injuries, careful evaluation is necessary to identify visceral damage. Delays in diagnosis may result in missed opportunities for timely surgical intervention and severe consequences. The diagnostic approach to closed abdominal injuries includes the following considerations:

Presence of Visceral Injury

In most cases, clinical manifestations are sufficient to determine whether visceral injury has occurred. However, early signs of visceral injury may be subtle in some patients or obscured by pain from localized abdominal wall trauma. Additionally, significant concurrent injuries may mask signs of intra-abdominal injury. For example, patients with concurrent cranial injuries may have impaired consciousness, preventing them from indicating symptoms, while coexisting thoracic injuries can cause severe chest pain and respiratory distress, and long bone fractures can lead to severe pain and impaired mobility. These factors can obscure signs and symptoms of abdominal injury, increasing the risk of missed diagnoses.

Thorough History Collection

Detailed information regarding the circumstances of the injury should be obtained, including the time, location, mechanism of injury, changes in condition, and emergency measures applied before hospital arrival. If the patient is unconscious or otherwise unable to provide information, witness accounts and reports from those accompanying the patient should be sought.

Vital Sign Monitoring

Monitoring of vital signs, including blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory rate, and body temperature, is essential to detect signs of shock.

Comprehensive and Focused Physical Examination

Examination should assess the nature and extent of tenderness, muscle guarding, and rebound tenderness in the abdomen, as well as changes in liver dullness, presence of abdominal shifting dullness, and signs of bowel motility inhibition. A digital rectal examination should also be performed to identify tenderness, fluctuance, or blood. Injury to areas outside the abdomen, especially sites where bullet or sharp weapon entry wounds may be connected to the abdominal cavity, should be thoroughly investigated.

Laboratory Testing

A significant drop in red blood cell count, hemoglobin levels, or hematocrit suggests substantial blood loss. Elevated white blood cell counts and increased neutrophils are commonly seen in visceral injury but may also reflect systemic stress responses and are not highly diagnostic. Elevated serum or urinary amylase levels may indicate pancreatic injury or gastrointestinal perforation, though not all cases are associated with increased amylase. Hematuria serves as a key indicator of urinary tract injury, although its severity does not always correlate with the severity of the injury.

Any of the following findings strongly suggests visceral injury:

- Early signs of shock, particularly hemorrhagic shock.

- Progressive abdominal pain accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea or vomiting.

- Pronounced peritoneal irritation.

- Evidence of free air in the abdomen (pneumoperitoneum).

- Shifting dullness in the abdomen.

- Blood in stools, vomitus, or urine.

- Positive findings on digital rectal examination, including anterior wall tenderness, fluctuance, or blood-stained gloves.

Refractory shock in patients with abdominal injuries typically suggests visceral injury as the primary cause, although concurrent injuries to other areas should also be considered.

Identification of the Injured Organ

The first step involves determining the type of organ affected, followed by identifying the specific organ and assessing the extent of the injury. In cases of isolated solid organ injury, symptoms such as abdominal pain, tenderness, and muscle guarding are not prominent. When the volume of bleeding is significant, abdominal distension and shifting dullness may be noted. However, after liver or spleen rupture, localized coagulated blood may lead to fixed dullness. Isolated hollow organ rupture typically presents with peritonitis as the primary clinical manifestation, with perforations of upper gastrointestinal organs being particularly severe. Ruptures in lower gastrointestinal tract organs may not show signs of peritonitis early on, with symptoms manifesting only after 48 to 72 hours. This delayed presentation may occur because small ruptures in the intestinal wall can temporarily seal off due to mucosal eversion or blockage by debris from intestinal contents. Despite the delayed onset of peritonitis, colonic rupture often results in severe septic shock due to a higher bacterial load and thus requires special attention.

The following findings are valuable in determining the organ involved in an injury:

- Nausea, vomiting, hematochezia, or pneumoperitoneum often indicate gastrointestinal tract injuries. When combined with the location of impact and the region of most pronounced peritoneal irritation, it may help pinpoint injuries to specific organs such as the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, or colon.

- Difficulty urinating, hematuria, or referred pain to the perineum or external genitalia suggests injury to the urinary system organs.

- Referred pain to the shoulder is suggestive of upper abdominal organ injury, most commonly liver or spleen rupture.

- Fractures of the lower ribs raise the possibility of liver or spleen rupture.

- Pelvic fractures suggest potential injuries to the rectum, bladder, or urethra.

Presence of Multiple Injuries

Multiple injuries may present in the following forms:

- Multiple injuries to a single intra-abdominal organ.

- Injuries involving more than one intra-abdominal organ.

- Concurrent injuries outside the abdomen in addition to abdominal injuries.

- Injuries outside the abdomen with secondary involvement of intra-abdominal organs.

Regardless of the specific situation, vigilance is required during diagnosis and treatment to avoid missed diagnoses and their potentially serious consequences. Key strategies to prevent misdiagnosis include thorough history-taking, detailed physical examinations, close monitoring, and maintaining a comprehensive perspective during diagnosis and management. For instance, in cases where a patient with cranial trauma exhibits low or unstable blood pressure, failure to promptly correct shock after managing the cranial trauma should raise suspicion of intra-abdominal hemorrhage. In the absence of brainstem compression or respiratory suppression, addressing intra-abdominal hemorrhage should take priority.

Management When Diagnosis is Challenging

When the aforementioned examinations and analyses fail to establish a definitive diagnosis, the following measures may be utilized.

Auxiliary Examinations

Diagnostic Peritoneal Aspiration and Lavage

The positive detection rate for these techniques exceeds 90%, making them highly valuable for assessing the presence of intra-abdominal organ injuries and identifying the type of injured organ. Common puncture sites for diagnostic peritoneal aspiration are located at the junction of the middle and outer third of the line connecting the umbilicus and anterior superior iliac spine, or at the intersection of the umbilical horizontal line and the anterior axillary line. A fine plastic catheter with multiple side holes is inserted into the abdominal cavity through a needle to perform aspiration. After fluid is aspirated, its nature (e.g., blood, gastrointestinal contents, turbid ascitic fluid, bile, or urine) is analyzed to identify the injured organ.

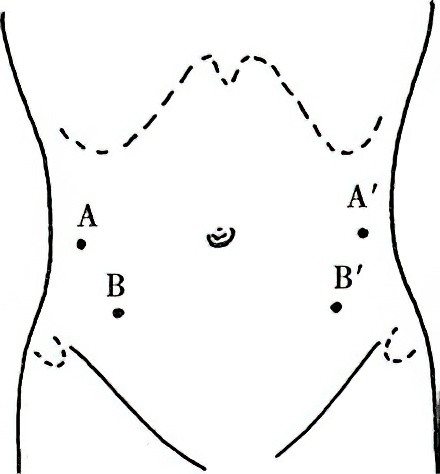

Figure 1 Needle insertion points for diagnostic peritoneal aspiration

A and A' indicate intersections of the umbilical horizontal line and anterior axillary line.

B and B' indicate points at the junction of the middle and outer third along the line connecting the anterior superior iliac spine and the umbilicus.

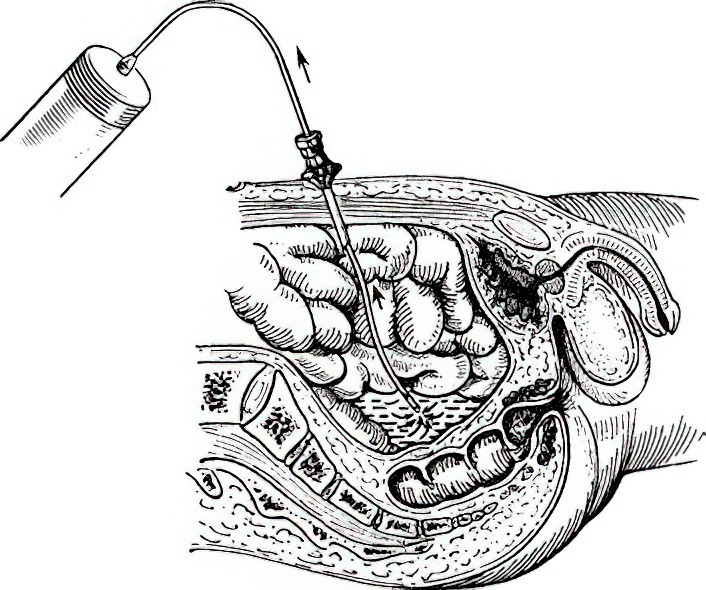

Figure 2 Method for aspirating fluid during diagnostic peritoneal aspiration

Smear evaluations of the aspirated fluid may be performed when necessary. Amylase levels can be measured if pancreatic injury is suspected. The presence of non-clotting blood suggests bleeding caused by organ rupture, with defibrination resulting from a fibrinolytic reaction in the peritoneum. The absence of fluid on aspiration does not exclude the possibility of organ injury; continued close observation is necessary, and repeat aspiration or diagnostic peritoneal lavage may be considered.

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage involves inserting a plastic catheter via the aforementioned puncture site, through which 500–1,000 mL of sterile saline is gradually infused into the abdominal cavity. The lavage fluid is then siphoned back into an infusion bottle, and its contents are analyzed visually or microscopically. Smears for bacterial cultures or amylase level tests may also be performed when necessary. This method is more sensitive than simple aspiration for detecting small amounts of bleeding within the abdominal cavity, facilitating early diagnosis. A positive result is indicated by the presence of any of the following:

- Grossly visible blood, bile, gastrointestinal contents, or confirmed urine in the lavage fluid.

- Red blood cell count exceeding 100×109/L or white blood cell count exceeding 0.5×109/L under microscopic examination.

- Amylase level exceeding 34.3 IU/L.

- Detection of bacteria in the lavage fluid.

The use of ultrasound-guided techniques for aspiration can enhance the safety and reliability of the diagnostic process.

X-ray Examination

If the diagnosis of abdominal organ injury is confirmed, especially in cases accompanied by shock, immediate intervention is warranted, and X-ray examination should be avoided to prevent treatment delays. However, if the patient’s condition permits, selective X-ray imaging can still provide diagnostic value. The most commonly used studies include chest X-rays and supine abdominal X-rays; pelvic X-rays may also be performed if necessary. In cases of pelvic fractures, attention should be paid to potential injuries to pelvic organs.

The presence of free intraperitoneal gas indicates gastrointestinal perforation (typically involving the stomach, duodenum, or colon, and less commonly the small intestine). An upright abdominal X-ray may reveal a crescent-shaped opacity beneath the diaphragm. Retroperitoneal free gas suggests perforation of the retroperitoneal duodenum or colorectal structures. In cases of significant intra-abdominal hemorrhage, the small intestine often shifts toward the central abdomen (in the supine position), with widened interloop spaces, and the gas-filled ascending and descending colons may separate from the peritoneal fat line. A retroperitoneal hematoma may manifest as the loss of the psoas muscle opacity.

Signs of splenic rupture include rightward gastric displacement, downward displacement of the transverse colon, and serrated indentations along the greater curvature of the stomach (indicative of hematoma within the gastrosplenic ligament). Elevated right hemidiaphragm, loss of normal liver contours, and fractures of the right lower ribs suggest possible liver rupture. Left diaphragmatic hernia may involve protrusion of the gastric bubble or intestinal loops into the thoracic cavity. Diagnosis of right diaphragmatic hernia is more challenging and may require diagnostic pneumoperitoneum to aid in diagnosis. Intravenous or retrograde pyelography can be used to diagnose urinary system injuries.

Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasound examination is widely used in clinical practice due to its simplicity and capability for dynamic monitoring of injuries. It is primarily employed to diagnose injuries to solid organs such as the liver, spleen, pancreas, and kidneys. This method can provide insights into the presence, location, and extent of damage based on the morphology and continuity of organ capsules as well as the presence of surrounding fluid accumulation. However, diagnosing hollow organ injuries can be challenging due to interference from intraluminal gas. If fluid accumulation is identified around a hollow organ, ultrasound-guided peritoneal aspiration may assist in diagnosis.

CT Examination

CT imaging is suitable for patients with stable conditions who require a precise diagnosis. CT scans clearly reveal the location and extent of solid organ damage and also provide some value in diagnosing hollow organ injuries. Contrast-enhanced CT may help identify the presence of active bleeding and its location.

Diagnostic Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is applicable for patients in generally stable condition when the presence or location of an injury remains uncertain. This method allows for direct visualization of injuries, enabling confirmation of the site and severity of damage. It is particularly useful for determining the presence of active bleeding, and therapeutic interventions can be performed under laparoscopic guidance, potentially avoiding unnecessary laparotomy. However, the use of carbon dioxide insufflation for laparoscopy can lead to hypercapnia and respiratory difficulties due to diaphragmatic elevation. In cases of major vein injury, gas embolism may occur. Techniques involving gasless laparoscopy are available to address such risks.

Other Examinations

When injuries to organs such as the liver, spleen, pancreas, kidneys, or duodenum remain unconfirmed despite the aforementioned diagnostic methods, selective angiography may provide diagnostic value. In cases of solid organ rupture, findings may include arterial contrast extravasation during the arterial phase, vascular exclusion in the parenchymal phase, or early venous filling during the venous phase. MRI examinations are highly valuable for diagnosing vascular injuries and certain hematomas in specific locations, such as duodenal wall hematomas. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is particularly useful for diagnosing biliary tract injuries.

Close Monitoring

Close observation is an important diagnostic measure for patients whose intra-abdominal injuries cannot be definitively confirmed but whose vital signs remain stable. Monitoring typically includes:

- Measurement of blood pressure, pulse rate, and respiratory rate at intervals of 15–30 minutes.

- Examination of abdominal signs every 30 minutes, with attention to changes in the degree and extent of peritoneal irritation.

- Measurement of red blood cell count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit every 30–60 minutes to detect any decline, along with monitoring for increases in white blood cell count.

- Repeat diagnostic peritoneal aspiration or lavage, ultrasound, or other procedures as needed.

During the observation period, in addition to monitoring changes in the condition, certain precautions should be taken:

- Avoid unnecessary movement of the patient to prevent exacerbation of injuries.

- Minimize or avoid the use of analgesics to prevent masking of symptoms.

- Withhold food and water to avoid exacerbating peritoneal contamination in cases of gastrointestinal perforation.

To prepare for potential surgical treatment, the following measures should be implemented during the observation period:

- Active replenishment of blood volume to prevent and manage shock.

- Administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics to prevent or treat potential intra-abdominal infections.

- Gastric decompression in cases of suspected hollow organ rupture or evident abdominal distension.

Exploratory Laparotomy

Exploratory laparotomy should be considered when abdominal organ injuries cannot be ruled out using the above methods or when the following conditions arise during observation:

- Progressive deterioration of the patient’s overall condition, including symptoms such as thirst, restlessness, rapid pulse, or shock, as well as increases in temperature or white blood cell count, or a progressive decline in red blood cell count.

- Worsening or expanding abdominal pain and signs of peritoneal irritation.

- Gradual weakening or disappearance of bowel sounds, or progressive abdominal distension.

- Presence of free air under the diaphragm, a reduction or disappearance of liver dullness, or the appearance of shifting dullness.

- Failure to improve or worsening of the condition despite active anti-shock measures.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Recovery of gas, non-clotting blood, bile, gastrointestinal contents, or other abnormal substances during peritoneal aspiration.

- Significant tenderness detected during rectal examination.

Although exploratory laparotomy may occasionally yield negative findings, a missed diagnosis of intra-abdominal organ injury could result in death. Therefore, laparotomy is worth performing as long as the indications are strictly observed.

Management

The principles for managing blunt abdominal wall injuries and stab wounds are similar to the treatment of other soft tissue injuries and will not be elaborated further. Penetrating open injuries and closed intra-abdominal injuries often require surgical intervention. In cases of penetrating injuries where intra-abdominal organs or tissues protrude through the abdominal wall wound, covering the exposed tissues with a sterile bowl for protection is recommended, avoiding forced reinsertion to prevent aggravating intra-abdominal contamination. Reinsertion should be performed under anesthesia.

For patients with confirmed or highly suspected intra-abdominal organ injuries, the management principle involves thorough emergency preoperative preparation and proceeding with surgery as early as possible. When injuries outside the abdomen coexist, comprehensive assessment should be conducted to prioritize life-threatening injuries, such as rapidly progressing traumatic brain injuries.

For critically ill patients, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and airway obstruction relief constitute the first priorities. Subsequently, controlling major hemorrhage and addressing open or tension pneumothorax become essential, alongside rapid restoration of circulatory blood volume and management of shock. In the absence of these additional conditions, the treatment of abdominal trauma should be prioritized.

Solid organ injuries, such as those involving the liver or spleen, frequently result in life-threatening hemorrhage and are therefore more urgent than hollow organ injuries, where peritonitis typically does not lead to death in the short term. Management and prevention of shock represent critical components in the treatment of abdominal injuries. In cases where shock is confirmed, sedatives or analgesics can be administered. For patients with intra-abdominal hemorrhage and shock, vigorous anti-shock measures are necessary, with surgery preferred once systolic blood pressure rises above 90 mmHg. If shock cannot be corrected, active intra-abdominal hemorrhage is suspected, and swift laparotomy for hemostasis should be performed while simultaneously managing the shock.

Hollow organ rupture tends to result in delayed-onset shock, often hypovolemic in nature, and surgery should proceed after stabilizing the shock. For cases of rupture accompanied by septic shock that is resistant to correction, surgery may still be performed alongside anti-shock measures. Use of sufficient broad-spectrum antibiotics is essential for hollow organ rupture cases.

Endotracheal intubation anesthesia is considered ideal, offering effective anesthesia, muscle relaxation, and oxygen supply while preventing aspiration during surgery. For patients with penetrating chest injuries, regardless of whether hemothorax or pneumothorax is present, closed thoracic drainage on the affected side should be arranged prior to anesthesia to prevent the occurrence of tension pneumothorax during positive-pressure ventilation.

A midline abdominal incision is commonly chosen for surgery, as it allows rapid entry into the abdominal cavity with minimal trauma and bleeding. This approach facilitates extension of the incision or combined thoracotomy if needed, and enables thorough exploration of all areas within the abdominal cavity. For open abdominal injuries, enlarging the existing wound for exploratory purposes may lead to infection and poor wound healing and should therefore be avoided.

In cases of intra-abdominal hemorrhage, accumulated blood should be aspirated immediately following laparotomy, with blood clots removed and the bleeding source identified and treated promptly. Common sources of bleeding include the liver, spleen, mesentery, and retroperitoneal areas involving the pancreas and kidneys. When determining the sequence of abdominal exploration, two considerations may be referenced:

- The injured organ suggested by preoperative diagnosis or judgment should be explored first.

- Bleeding sources are often located where blood clots are most concentrated.

For severe and life-threatening hemorrhage where the source cannot be immediately determined, temporary digital compression of the abdominal aorta at the diaphragm can be used to control bleeding, providing time for blood volume resuscitation before further investigation and treatment.

If no significant intra-abdominal bleeding is present, a methodical and systematic exploration of the abdominal organs should be conducted. This typically begins with solid organs such as the liver and spleen, followed by inspection for diaphragm and gallbladder injuries. The gastrointestinal tract is then examined sequentially, starting from the stomach, and continuing through the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, and their mesenteries. Pelvic organs are subsequently evaluated. The gastrocolic ligament may need to be incised to expose the omental bursa for examination of the posterior gastric wall and pancreas. Retroperitoneal organs, including the descending, horizontal, and ascending segments of the duodenum, should be examined last if necessary.

Hemorrhagic injuries or organ ruptures discovered during exploration should be addressed immediately with hemostasis or clamping of ruptures. Exploration sequence may also be adjusted based on intraoperative findings when the peritoneum is incised. For instance, the presence of escaping gas suggests gastrointestinal rupture; food debris indicates upper gastrointestinal tract involvement; fecal matter suggests lower gastrointestinal tract involvement; and bile points to injuries in the extrahepatic biliary system or duodenum. The site of perforation is often found at locations with the highest fibrin deposition or omental wrapping.

After completing the exploration, a comprehensive assessment of the injuries should guide treatment priorities. Bleeding injuries are typically addressed before hollow organ ruptures. For hollow organ injuries, heavily contaminated areas are treated before less contaminated areas.

Before abdominal closure, residual fluids and foreign materials should be thoroughly removed, restoring the normal anatomical relationships of the intra-abdominal organs. The abdominal cavity should be irrigated with physiological saline, with heavily contaminated areas receiving repeated flushing. Suitable drainage methods, such as latex tubing or double-lumen suction, may be applied as needed. If the abdominal wall incision is not heavily contaminated, layered closure may be performed. In cases of significant contamination, subcutaneous drainage with latex strips may be used, or the skin and subcutaneous tissues may be temporarily left open for delayed closure.