Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) refers to the abnormal clotting of blood within the deep venous system, resulting in obstruction of the venous lumen and impaired venous return. Without timely treatment, complications such as pulmonary embolism may occur during the acute phase, while post-thrombotic syndrome may affect quality of life and work in the long term. DVT can occur in any major venous trunk of the body, with the lower extremities being the most commonly affected.

Etiology and Pathology

In the mid-19th century, Virchow proposed three primary factors responsible for deep venous thrombosis: venous endothelial damage, slowed blood flow, and hypercoagulable states.

Venous Endothelial Damage

This causes the loss of endothelium and exposure of subendothelial collagen or functional impairment of the venous endothelium, which leads to the release of bioactive substances that activate the endogenous coagulation system. At the same time, changes in the surface charge of the venous walls promote platelet aggregation and adhesion, resulting in thrombus formation.

Slowed Blood Flow

External factors, such as prolonged bed rest, intraoperative and postoperative immobility, limb immobilization, and prolonged sitting, are common contributors.

Hypercoagulable States

These occur in conditions such as pregnancy, the postpartum period, postoperative periods, trauma, prolonged use of oral contraceptives, and with tumor cell breakdown products.

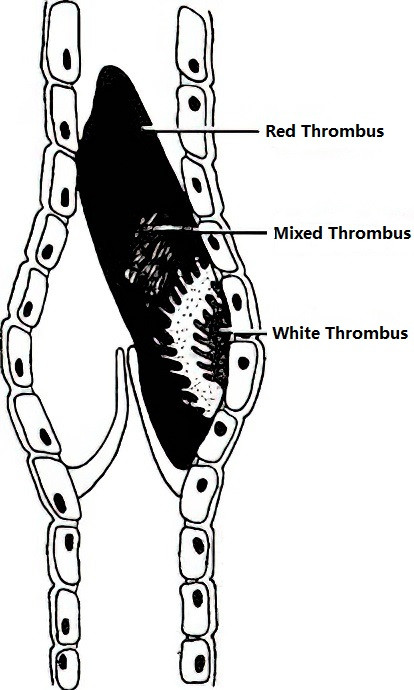

Thrombi typically consist of a white thrombus at the head, a mixed thrombus at the neck, and a red thrombus at the tail. Thrombus formation can extend proximally and distally along the venous trunk. Under the influence of fibrinolysin (plasmin), the thrombus may dissolve or disintegrate into embolic fragments, which flow with the bloodstream into the pulmonary arteries, leading to pulmonary embolism. Thrombosis also triggers an inflammatory response in the venous wall and surrounding tissues, causing the thrombus to adhere to the vein wall, undergo fibrous organization, and form recanalized veins with irregular walls and variable lumen diameters. Venous valve damage often follows, resulting in secondary lower extremity deep vein valve insufficiency, also known as post-thrombotic syndrome.

Figure 1 Anatomical pathology of a typical thrombus

Clinical Manifestations and Classification

DVT can be classified into three categories based on the site of thrombosis:

Upper Extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis

Thrombosis limited to the axillary vein causes swelling and pain localized to the forearm and hand. When the axillary-subclavian veins are involved, the entire upper limb becomes swollen, with dilated superficial veins in the affected shoulder, supraclavicular area, and anterior chest wall. Swelling and pain worsen when the limb is in a dependent position but improve upon elevation.

Superior and Inferior Vena Cava Thrombosis

Superior Vena Cava Thrombosis

This is typically caused by malignancies in the mediastinum or lungs. In addition to upper extremity venous obstruction, symptoms include swelling of the face and neck, conjunctival congestion and edema, and eyelid swelling. Dilated superficial veins are visible in the neck, anterior chest wall, and shoulders, often extending to the contralateral side. Blood flow in the dilated chest wall veins typically moves in a downward direction. Other associated features include headache, a sense of head fullness, neurological symptoms, and symptoms related to the underlying malignancy.

Inferior Vena Cava Thrombosis

This frequently results from upward extension of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. Clinical manifestations include bilateral lower extremity venous obstruction and dilation of superficial veins on the trunk, with blood flow in these veins directed upward. Thrombosis involving the hepatic segment of the inferior vena cava can lead to Budd-Chiari syndrome, characterized by impaired hepatic venous drainage.

Lower Extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis

This is the most common presentation and can be classified based on the site and timing of thrombus formation:

Classification based on thrombus location:

- Central Type: Involves iliac-femoral vein thrombosis. Symptoms include acute onset, significant swelling of the entire lower limb, pain and tenderness in the iliac fossa and femoral triangle, superficial vein dilation, and increased limb and body temperature. The left leg is more commonly affected than the right.

- Peripheral Type: Involves femoral vein or deep calf vein thrombosis. Femoral vein thrombosis presents with thigh swelling and pain, but lower limb swelling is often mild due to patent iliac-femoral veins. Deep calf vein thrombosis features sudden onset of calf pain, inability to bear weight on the affected foot, and worsening of symptoms with walking. The calf is swollen, with deep tenderness and pain during forced dorsiflexion of the ankle (positive Homan's sign).

- Mixed Type: Involves thrombosis of the entire lower extremity deep venous system.

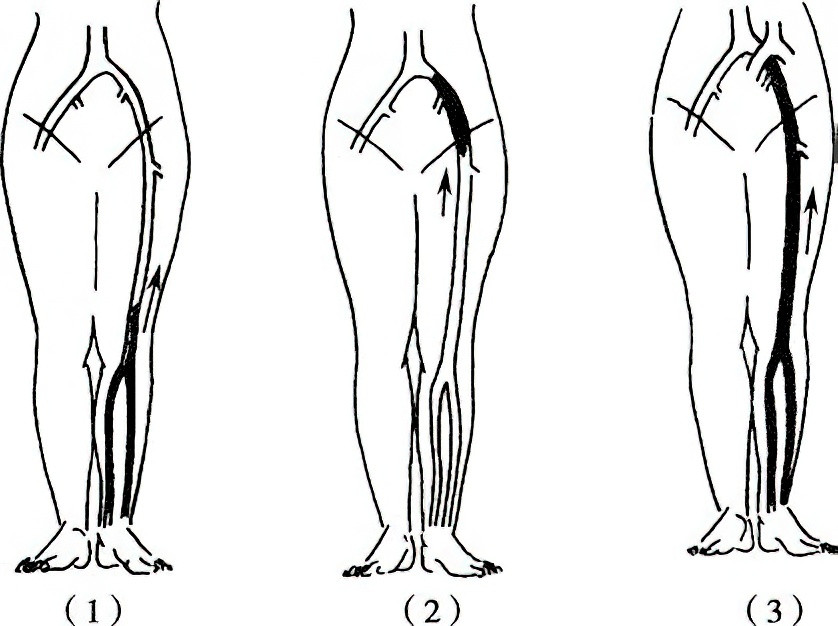

Figure 2 Types of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis

1, Peripheral Type

2, Central Type

3, Mixed Type

Symptoms include significant swelling and severe pain involving the entire lower limb, with tenderness in the femoral triangle, popliteal fossa, and calf muscles. Other features include fever and a rapid pulse. In advanced cases, extreme swelling may cause compression of lower limb arteries and lead to arterial spasm, resulting in impaired arterial blood supply. Absent pulsations in the dorsal pedis artery and posterior tibial artery may occur, accompanied by blistering on the calf and foot, cyanosis, and cool skin temperature (phlegmasia cerulea dolens). Without intervention, venous gangrene may develop.

Classification based on timing of onset:

- Acute Phase: Within 14 days of onset.

- Subacute Phase: Onset between 15 and 30 days.

- Chronic Phase: After 30 days of onset.

Classification based on clinical course:

- Occlusive Type: Early in the disease, the deep venous lumen is obstructed, characterized by significant swelling and pain in the affected limb, along with widespread superficial vein dilation. Nutritional skin changes in the calf are typically absent.

- Partially Recanalized Type: During the mid-stage of the disease, partial recanalization of deep veins occurs. Limb swelling and pain improve, but superficial vein dilation becomes more pronounced or varicose. Distal pigmentation of the calf may develop.

- Recanalized Type: Later in the disease, most or all of the deep veins become recanalized. Limb swelling may improve but often worsens after activity. Prominent superficial varicose veins, widespread calf hyperpigmentation, and chronic recurrent ulcers may develop.

- Recurrent Type: Recurrent acute thrombosis occurs within previously recanalized deep veins.

Examination and Diagnosis

The sudden onset of unilateral limb swelling accompanied by distension, pain, and superficial vein dilation raises the suspicion of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Clinical diagnosis is typically straightforward based on the symptoms associated with DVT at different venous sites. The following investigations are helpful in confirming the diagnosis and determining the extent of the condition:

Doppler Ultrasound

Doppler ultrasound can detect signs of thrombosis, such as strong echogenicity within the venous lumen, lack of venous compressibility, or absence of blood flow. Repeated examinations allow for the monitoring of disease progression and treatment efficacy.

Lower Extremity Antegrade Venography

Diagnostic features include:

- Obstruction or Interruption: Complete occlusion of deep venous trunks leading to no opacification, or sudden blockage of contrast flow at a specific venous plane. This is commonly observed during the acute phase of thrombosis.

- Filling Defects: Persistent, cylindrical or irregular intraluminal contrast density reductions of varying lengths with linear contrast margins forming a "track sign." This is a direct indicator of venous thrombosis and confirms acute DVT.

- Recanalization: Irregular narrowing or branching of the venous lumen, with portions showing dilation or even tortuosity, observed during the subacute or chronic phase of thrombosis.

- Formation of Collateral Circulation: Irregular collateral venous pathways become evident around the obstructed vein. Enlarged great and small saphenous veins often serve as key collateral routes.

Prevention and Treatment

Surgical procedures, immobilization, and hypercoagulable states are high-risk factors for DVT. Methods such as anticoagulation therapy, antiplatelet drugs, and encouraging active mobilization of limbs or early ambulation are effective preventive measures. Treatment strategies are categorized into non-surgical and surgical approaches, which are selected based on the type of lesion and the clinical stage of the disease.

Non-Surgical Treatment

General Management

This includes bed rest with limb elevation and the judicious use of diuretics to alleviate limb swelling. When the condition stabilizes, medical compression stockings or elastic bandages may be worn, and ambulation can gradually resume.

Antiplatelet Drugs

Medications such as aspirin and dextran can increase blood volume, reduce blood viscosity, and prevent platelet aggregation. These agents are often used as adjunctive therapy.

Anticoagulant Therapy

This is the cornerstone of DVT treatment, aiming to prevent thrombus formation, stop thrombus propagation, and facilitate vein recanalization. Anticoagulants include unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin (molecular weight < 6,000), vitamin K antagonists, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). DOACs can be further divided into direct thrombin inhibitors and factor Xa inhibitors. Treatment often begins with subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin to achieve a low-coagulability state, followed by oral administration of vitamin K antagonists (e.g., warfarin) or DOACs. Individualized anticoagulation plans should be developed based on the patient's condition and disease stage, with treatment lasting at least 3 months.

Thrombolysis

Intravenous infusion of thrombolytic agents such as streptokinase, urokinase, or tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) promotes the activation of plasminogen in plasma, converting it into plasmin, which dissolves thrombi.

Complications such as bleeding associated with anticoagulant and thrombolytic therapy require careful monitoring of coagulation parameters. During fibrinolytic therapy, fibrinogen levels should be monitored and kept above 1.0 g/L (normal levels: 2–4 g/L). If bleeding complications arise, medications should be discontinued, and specific countermeasures should be employed, such as protamine sulfate to neutralize heparin or vitamin K1 for warfarin reversal. Bleeding caused by fibrinolytic therapy may be treated with 10% epsilon-aminocaproic acid, fibrinogen supplements, or transfusion of fresh blood.

Surgical Treatment

Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis (CDT)

This endovascular technique is used for acute central or mixed DVT. Under ultrasound or venographic guidance, a thrombolysis catheter is inserted either antegradely or retrogradely into the thrombus through the appropriate vein. Thrombolytic agents are continuously delivered via the catheter's side port in a pulsatile manner, ensuring thorough contact with the thrombus. This method achieves superior thrombolytic effects while reducing the risk of bleeding complications, and is safer than systemic thrombolysis via peripheral veins.

Mechanical Thrombectomy

Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy (PMT) is suitable for fresh thrombosis (< 14 days) in the acute stage. The technique uses rotational turbine or hydrodynamic mechanisms to fragment or aspirate the thrombus, which helps reduce or eliminate thrombosis burden rapidly and relieve venous obstruction. When combined with catheter-directed thrombolysis, the required dose of thrombolytic drugs and hospital stay can be significantly reduced.

Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) Filter Placement

This is recommended for patients with contraindications to anticoagulation therapy and reduces the risk of pulmonary embolism. However, the indication for IVC filter placement is strictly controlled. Long-term implantation carries risks of inferior vena cava obstruction and recurrent DVT. Hence, retrievable filters are preferred, which should be promptly removed once the risk diminishes.

Complications and Sequelae

When a deep venous thrombus dislodges and enters the pulmonary artery, it can result in a pulmonary embolism (PE). Massive pulmonary embolism can be fatal, whereas smaller, localized PEs often lack specific clinical manifestations. Typical symptoms include dyspnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, hypotension, and hypoxemia. In severe cases, acute onset may lead to rapid syncope accompanied by chills, sweating, pallor or cyanosis, and significant blood pressure reduction. Pulmonary artery CTA (computed tomography angiography) is effective in confirming the diagnosis. For patients with a history of pulmonary embolism, thrombus extending toward the inferior vena cava, or those at risk of dislodged thrombi due to thrombectomy or catheter procedures, placement of an inferior vena cava filter may be considered to prevent the occurrence of pulmonary embolism.

Following deep venous thrombosis (DVT), as thrombi undergo organization and recanalization, venous return gradually improves; however, damage to the deep venous valves often leads to worsening venous reflux symptoms. This condition may result in post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS). The management of PTS varies according to the type of pathology. For cases primarily characterized by occlusion, non-surgical therapies remain the primary treatment. In recent years, endovascular intervention to re-open the occluded venous segments has been performed, with stent placement utilized to relieve venous outflow obstruction in selected patients, improving clinical symptoms. However, the long-term efficacy of these interventions requires further evaluation.