Arterial embolism refers to the blockage of an artery caused by an embolus (such as a thrombus, air, fat, tumor emboli, or other foreign materials) that has entered the vascular system. This condition results in blood flow obstruction and clinical manifestations of acute ischemia. It is characterized by sudden onset, pronounced symptoms, rapid progression, severe consequences, and the need for prompt management.

Etiology and Pathology

The primary sources of emboli include the following:

- Cardiogenic: This is the most common cause of arterial embolism, as seen in conditions such as atrial fibrillation, rheumatic heart disease, or infective endocarditis. Thrombi may detach from the atrial or ventricular walls or from artificial heart valves.

- Vascular Origin: Emboli may arise from thrombi within an arterial aneurysm or from dislodged atherosclerotic plaques.

- Iatrogenic: Foreign materials such as catheters, guidewires, embolization agents, or stents used during intravascular procedures can lead to embolism.

- Other Origins: Fat embolism may occur following fractures or liposuction. Amniotic fluid embolism can arise during childbirth, and malignant tumors may produce emboli known as tumor emboli.

Emboli are often carried with the bloodstream to the arteries of the brain, internal organs, or extremities and typically lodge at arterial bifurcation sites. Severe ischemia lasting 6–12 hours can lead to tissue necrosis and associated muscle and nerve dysfunction.

Clinical Manifestations

The classic clinical presentation of acute arterial embolism is summarized by the "5 Ps": pain, pallor, pulselessness, paresthesia, and paralysis.

Pain

Pain is usually the earliest symptom and is caused by arterial spasm at the embolic site and a sudden increase in proximal arterial pressure. It begins at the site of embolism and radiates distally, eventually evolving into persistent pain. Even slight changes in limb position or passive movement can induce severe pain, leading to a forced position with mild flexion of the affected limb.

Changes in Skin Color and Temperature

Arterial blood flow obstruction results in subcutaneous venous blood drainage, causing pallor of the skin. Skin temperature in the distal limb becomes reduced or even cold. The extent of the temperature gradient can help estimate the embolism site, with the affected cold area usually extending about one palm's width below the embolism site.

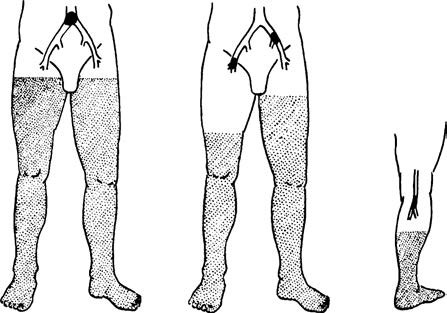

Figure 1 Changes in skin temperature following arterial embolism at different locations

The shaded areas represent regions with reduced skin temperature, which are all located distal to the actual site of embolism.

Diminished or Absent Arterial Pulses

Following acute embolism, the arterial pulse distal to the embolic site becomes significantly reduced or absent. Palpation of the pulses in different segments of the affected limb can assist in approximating the embolic location.

Sensory and Motor Impairment

Ischemia of the peripheral nerves results in sensory abnormalities, numbness, or loss of sensation in the distal limb. In later stages, muscle necrosis can develop, leading to loss of deep sensation, impaired motor function, and varying degrees of foot or wrist drop.

Systemic Effects of Arterial Embolism

The larger the occluded artery, the more severe the systemic response. Tissue ischemia and necrosis in the affected limb can lead to serious metabolic disturbances, manifesting as hyperkalemia, myoglobinuria, and metabolic acidosis, which may eventually result in kidney failure.

Diagnostic Evaluation

A clinical diagnosis can be established if an individual with a history of heart disease (such as atrial fibrillation) or other causative factors suddenly develops the "5 Ps" symptoms. The following examinations provide objective evidence to confirm the diagnosis:

- Arterial Pulse Palpation: This helps approximate the embolic site.

- Doppler Ultrasound: This detects the abrupt loss of arterial flow in major limb arteries and can identify the embolic location.

- Arteriography and CTA: These methods provide detailed information about the embolic site, patency of distal arteries, condition of collateral circulation, and the presence of secondary thrombosis.

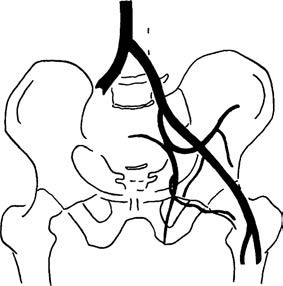

Figure 2 Right common iliac artery embolism

The contrast agent abruptly stops at the proximal end of the embolism site.

In addition to confirming the diagnosis, investigations should focus on identifying the source of the embolism. Tests such as electrocardiograms, echocardiograms, blood biochemistry, and enzyme assays are important for formulating a systemic treatment plan.

Treatment

Given the rapid progression and severe consequences of arterial embolism, effective treatment should be promptly initiated once the diagnosis is confirmed.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Non-surgical treatment is often considered because patients frequently have severe underlying cardiovascular conditions. Even when emergency thrombectomy is planned, perioperative management is critical to improve the patient’s overall condition and minimize surgical risks. Non-surgical treatment is particularly suitable in the following scenarios:

- Patients whose overall condition is too poor to tolerate surgery.

- Embolism involving distal small arteries, such as the distal tibio-peroneal trunk or the distal brachial artery.

- Cases where the embolic event occurred some time ago or there is well-established collateral circulation capable of maintaining limb viability.

- Situations where the affected limb shows obvious signs of necrosis and surgery would no longer save it.

Commonly used medications include anticoagulants, antiplatelet drugs, vasodilators, and thrombolytic agents. Low molecular weight heparin serves as a fundamental treatment for arterial embolism, helping to prevent secondary thrombus extension. Subsequent therapy may incorporate coumarin derivatives or direct oral anticoagulants. Fibrinolytic drugs, such as urokinase, can be administered systemically through peripheral veins or locally via arterial catheters placed at the site of the embolism. Continuous monitoring of coagulation function is necessary during treatment, and adjustments to dosages or discontinuation of medication are required as needed to prevent hemorrhagic complications involving critical organs.

Surgical Treatment

For confirmed diagnoses, especially in cases of large or medium-sized arterial embolism, surgical intervention should be performed as early as possible if the patient’s overall condition allows. The main surgical procedures include arterial thrombectomy, arterial bypass grafting, and endovascular treatments.

Arterial thrombectomy represents the primary strategy for the treatment of acute arterial embolism. This involves either direct thrombus removal through an arterial incision or the use of a Fogarty balloon catheter, the latter being more commonly applied due to its simplicity, shorter operative time, and reduced invasiveness. Endovascular treatments, such as percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy, provide therapeutic options for patients with poor general condition who cannot tolerate open surgery.

Postoperatively, close monitoring of the blood supply to the affected limb is essential, along with the continuation of treatment for related systemic diseases. If the affected limb exhibits swelling, muscle stiffness, or pain that causes renewed ischemia in previously reperfused distal tissues, early fasciotomy may be necessary. In cases of extensive muscle necrosis, amputation may need to be performed.