Mitral regurgitation (also known as mitral insufficiency) can result from various causes such as rheumatic disease, degenerative changes, infective endocarditis, and ischemic heart disease. Rheumatic mitral regurgitation is often associated with stenosis, and the primary pathological changes include thickening and shortening of the leaflets and chordae tendineae, reduced valve area, restricted leaflet mobility, and dilatation of the mitral annulus. With the increasing number of elderly patients, cases of degenerative valve disease have become more prevalent, in which the main pathological changes include partial chordal rupture and leaflet prolapse. Infective endocarditis may lead to the formation of vegetations or leaflet perforations. Ischemic heart disease can result in papillary muscle dysfunction, contributing to mitral regurgitation. Functional mitral regurgitation refers to cases without significant structural abnormalities of the valve apparatus (leaflets, chordae tendineae, or papillary muscles).

Pathophysiology

During left ventricular systole, a portion of blood flows back into the left atrium, reducing the effective blood volume entering the systemic circulation. The increased blood volume and pressure in the left atrium lead to compensatory enlargement of the atrium and further dilation of the mitral annulus, worsening regurgitation. The increased preload in the left ventricle over time results in ventricular remodeling, eventually causing left ventricular failure. Chronic pulmonary venous congestion induced by regurgitation may elevate pulmonary circulatory pressure, ultimately leading to right heart failure.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with mild disease and well-compensated cardiac function may remain asymptomatic. However, in severe or longstanding cases, symptoms may include fatigue, palpitations, and exertional dyspnea. Acute pulmonary edema and hemoptysis are less common compared to mitral stenosis. After the onset of symptoms, disease progression may deteriorate rapidly.

Physical Examination

Key findings include enhanced apex beat shifted leftward and downward. Auscultation of the apex may reveal a holosystolic murmur radiating to the left midaxillary line. Other findings include accentuated pulmonary valve area second heart sound and diminished or absent first heart sound. Late-stage cases may exhibit signs of right heart failure, such as hepatomegaly, ascites, and peripheral edema.

Auxiliary Examinations

Electrocardiography (ECG)

Mild cases may show normal ECG findings. More severe cases often demonstrate left axis deviation, P-mitrale, left ventricular hypertrophy, and strain.

X-ray Examination

Findings include significant enlargement of the left atrium and left ventricle. Barium esophagography may show posterior displacement of the esophagus due to left atrial compression.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is the most effective method for evaluating disease severity. M-mode echocardiography reveals double-peaked or single-peaked curves for the anterior mitral leaflet, with increased rates of ascent and descent. Significant enlargement of anteroposterior diameters of the left atrium and ventricle may be seen, as well as clear concave waves on the posterior wall of the left atrium.

In cases with concurrent stenosis, rectangular "castle wall-like" curves remain visible. Two-dimensional or cross-sectional echocardiography can directly visualize incomplete mitral valve closure during systole. Doppler echocardiography detects turbulent blood flow during diastole and estimates the severity of regurgitation.

Patients over 50 years of age or with coronary artery disease risk factors should undergo coronary angiography to rule out coronary artery disease.

Treatment

Patients with significant symptoms, impaired cardiac function, and cardiac enlargement should undergo open-heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass promptly. Surgical options include:

Mitral Valve Repair and Reconstruction

This procedure involves repairing the mitral valve using the patient’s own tissues combined with artificial materials to restore function. It includes reconstructing and reducing the annulus, shortening or lengthening the papillary muscles and chordae tendineae, implanting artificial rings and chordae, and repairing the leaflets. Due to variations in lesion types and surgical techniques, postoperative evaluation of repair effectiveness is essential, either intraoperatively or postoperatively via transesophageal echocardiography after the heart begins beating again. For persistent regurgitation, additional repair or mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic valve may be required.

Recently, minimally invasive catheter-based mitral valve repair has become a clinical option, primarily for patients with surgical contraindications or high-risk functional mitral regurgitation. Preliminary studies suggest better outcomes compared to medical therapy alone; however, efficacy compared to surgical repair remains controversial and requires further clinical research.

Mitral Valve Replacement

In cases of severe valve damage unsuitable for repair, mitral valve replacement is performed. The diseased leaflets and chordae are excised, and a prosthetic valve is sutured to the annulus.

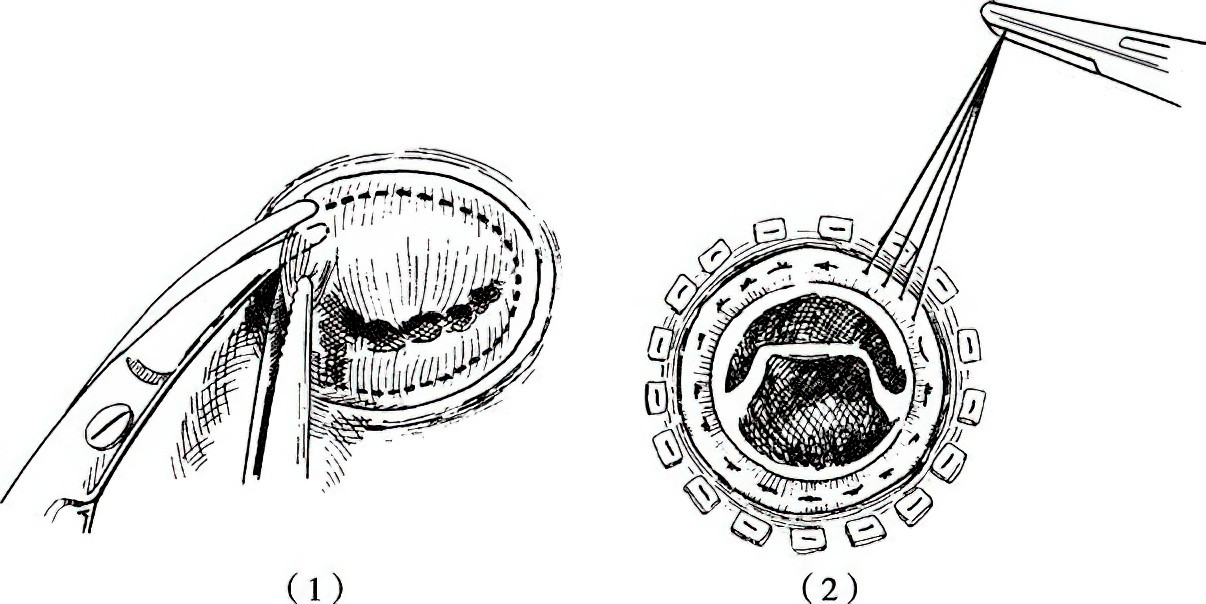

Figure 1 Mitral valve replacement procedure

1, Removal of the diseased mitral valve, preserving a small portion of leaflet tissue along the annulus.

2, Suturing and fixation of the mechanical prosthetic valve to the annulus.

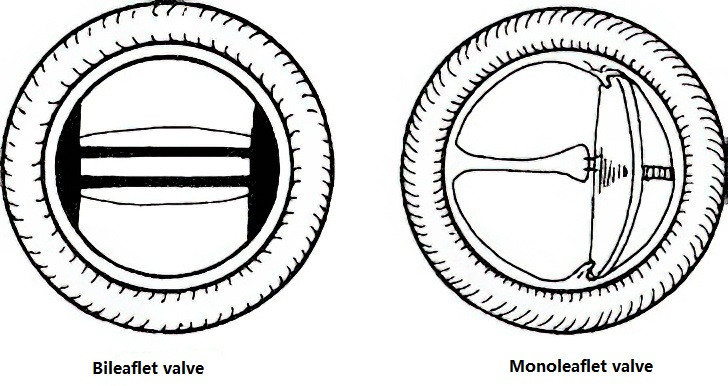

Figure 2 Mechanical valves

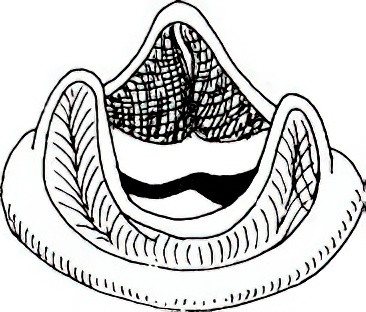

Figure 3 Bioprosthetic valve

Clinical prosthetic valves include mechanical valves and bioprosthetic valves. Each type has its advantages and disadvantages, and selection depends on patient factors. Proper post-operative management is crucial, including maintaining cardiac function, anticoagulant therapy after mechanical valve implantation, and long-term patient follow-up and care.