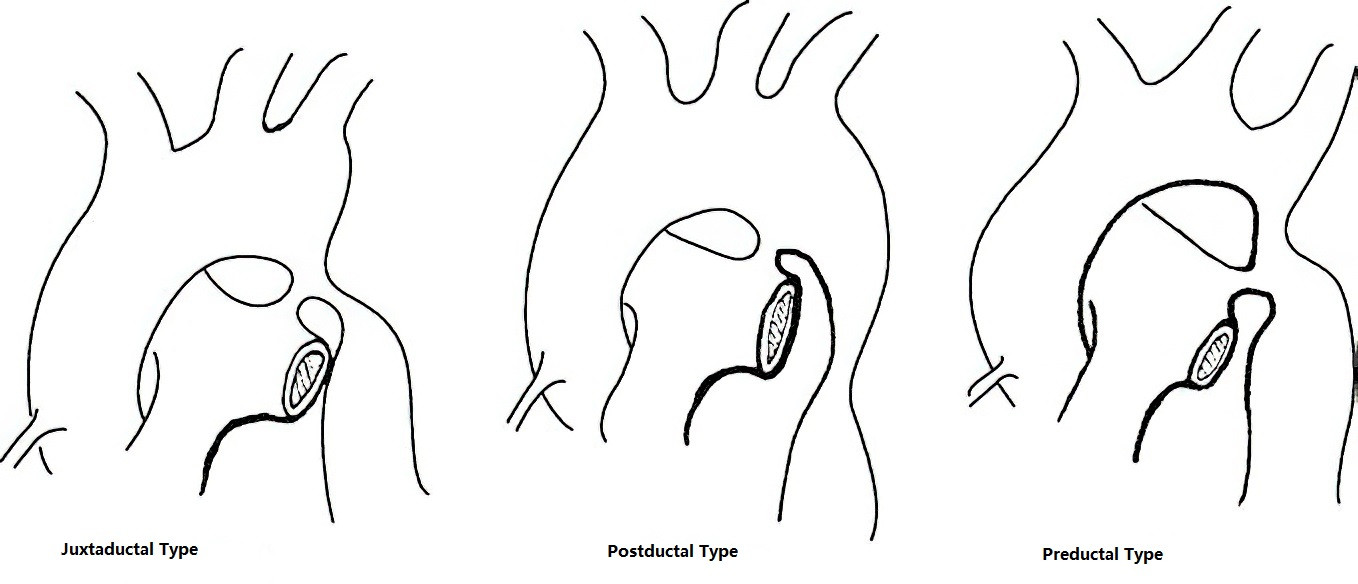

Aortic coarctation refers to a localized narrowing of the aortic lumen distal to the aortic arch, resulting in a significant pressure gradient between the proximal and distal ends. Based on its relationship with the ductus arteriosus (or ligamentum arteriosum), aortic coarctation is classified into the following types:

- Preductal Type (Infantile Type): The narrowing occurs proximal to the ductus arteriosus opening, which remains patent in these cases and supplies blood to the descending aorta. The narrowing is often extensive and frequently involves the aortic arch, commonly associated with ventricular septal defect, bicuspid aortic valve, and mitral stenosis.

- Postductal or Juxtaductal Type (Adult Type): The narrowing is located distal to or adjacent to the ductus arteriosus opening, which in most cases is closed. Cardiac anomalies are less commonly associated with this type. Extensive collateral circulation can form below the site of coarctation, involving the 3rd to 7th intercostal arteries and branches of the subclavian artery.

Figure 1 Classification of aortic coarctation

Pathophysiology

Proximal to the coarctation, blood pressure is elevated, leading to an increased afterload on the left ventricle, left ventricular hypertrophy, and eventual left ventricular strain or heart failure. This elevation in blood pressure may also predispose patients to conditions like stroke. Distally, blood pressure is reduced, resulting in decreased blood flow. Severe cases may lead to renal ischemia, lower body hypoperfusion, hypoxia, oliguria, and metabolic acidosis. In the preductal type, collateral circulation is often insufficient, and some pulmonary blood flow is channeled to the descending aorta via the ductus arteriosus, resulting in cyanosis in the lower body. In the postductal type, extensive collateral circulation develops, and enlarged intercostal arteries may lead to aneurysm formation.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms

The severity and onset of symptoms depend on the degree of narrowing and the presence of associated cardiac anomalies. In mild cases without cardiac anomalies, symptoms may be absent and the condition is often identified during routine physical examinations based on differences in upper and lower extremity blood pressure. Patients with significant narrowing may present with hypertension-related symptoms such as headache, dizziness, tinnitus, blurred vision, dyspnea, palpitations, and facial flushing, as well as ischemia-related symptoms like numbness, coldness, or intermittent claudication in the lower extremities. Severe coarctation associated with cardiac anomalies may manifest early in life with congestive heart failure, feeding difficulties, and growth retardation during infancy.

Physical Signs

Blood pressure is elevated in the upper extremities, with stronger pulsations in the radial and carotid arteries. Blood pressure is reduced in the lower extremities, and pulses in the femoral and dorsalis pedis arteries are weak or absent. A systolic ejection murmur may be auscultated at the second to third intercostal spaces along the left sternal border and in the scapular area of the back. In cases with associated cardiac anomalies, additional murmurs may be heard in the precordial region. Some patients may exhibit differential cyanosis.

Auxiliary Examinations

Electrocardiography (ECG)

Normal findings or evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy and strain may be observed.

Chest X-Ray

Left ventricular enlargement and indentation of the aortic isthmus are often visible. Widening of the mediastinal opacity above and below the indentation may create a "3" sign on imaging. In patients older than seven years, notching of the inferior borders of the 3rd to 9th ribs can be seen, caused by dilated intercostal arteries.

Echocardiography

Examination of the supraclavicular fossa may assist in diagnosis, revealing the site of coarctation, the pressure gradient between the proximal and distal ends, and accelerated blood flow signals. Precordial imaging can identify any associated cardiac anomalies.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is straightforward in typical cases based on the features outlined above. Advanced imaging techniques such as computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or aortic angiography can provide detailed information about the location, extent, and severity of the coarctation, as well as its anatomical relationship with surrounding vessels and the distribution of collateral circulation. These findings are useful for formulating an individualized treatment plan.

Treatment

Indications for Surgery

Surgical intervention is indicated for isolated aortic coarctation when the systolic blood pressure difference between the upper and lower limbs exceeds 50 mmHg, the diameter of the coarctation site is less than 50% of the normal aortic segment, or the upper limb systolic blood pressure is greater than 150 mmHg. For infants and young children with recurrent pulmonary infections, heart failure, or associated cardiac anomalies (such as hypoplasia of the aortic arch, patent ductus arteriosus, or ventricular septal defect), early surgery and one-stage repair are recommended.

For asymptomatic cases of isolated aortic coarctation, elective surgery between the ages of 4 and 6 years is currently considered appropriate. Surgery performed at too young an age increases the risk of long-term restenosis, while surgery at an older age increases the likelihood of secondary vascular changes such as atherosclerosis in the aortic branches.

Surgical Methods

For patients with poorly developed collateral circulation, measures such as hypothermia, temporary vascular shunts, or left heart bypass are used to protect the spinal cord, kidneys, and abdominal organs from ischemic injury caused by clamping the descending thoracic aorta. Hypothermic anesthesia at 32°C can extend the safe duration for aortic occlusion to 30 minutes. The surgical procedure is performed with the patient in the right lateral decubitus position, accessing the left thoracic cavity through the fourth intercostal space. The choice of surgical technique depends on the patient’s age, the location and severity of the coarctation, and the local anatomy. For infants and young children with associated cardiac anomalies, a midline sternotomy can be used to establish cardiopulmonary bypass for simultaneous correction of intracardiac defects and aortic coarctation. The primary surgical techniques include:

Resection of the Coarcted Segment with End-to-End Anastomosis:

This is suitable for localized coarctation where the resected ends can be anastomosed without tension.

Subclavian Flap Aortoplasty

This involves ligation and dissection of an adequate length of the left subclavian artery, which is then longitudinally opened to create a pedicled flap for use as a patch to enlarge the coarcted segment. This method is appropriate for infants and young children with a relatively large left subclavian artery and a longer coarctation segment. Advantages include the use of autologous tissue with potential for growth and a lower incidence of restenosis postoperatively.

Patch Aortoplasty

This involves longitudinally incising the coarctation site and widening it with an artificial patch. Recently, the use of autologous pulmonary artery patches has been reported as an alternative to synthetic materials. This method is suitable for cases with a long coarctation segment or when end-to-end anastomosis is difficult. Its main disadvantage is a higher risk of aneurysm formation.

Resection of the Coarcted Segment with Artificial Graft Replacement

This method is indicated for patients with long coarctation segments. Since artificial grafts cannot grow, this approach is generally avoided in pediatric patients.

Artificial Graft Bypass

This involves connecting the proximal and distal ends of the coarctation site using an appropriately sized artificial graft, accessed via the fourth intercostal space or in combination with a midline incision. This method is suitable for cases where the coarctation site is difficult to expose, resection is challenging, or restenosis requires reoperation.

Balloon Angioplasty and Endovascular Stent Placement

Balloon angioplasty is performed by percutaneous insertion of a catheter to dilate the narrowed aortic segment. A stent can be placed following angioplasty to provide structural support, preventing elastic recoil of the vessel wall and reducing the risk of restenosis. The stent can also minimize vascular tearing and bleeding caused by dilation while lowering the risk of aneurysm formation. This approach is appropriate for adults and older children.