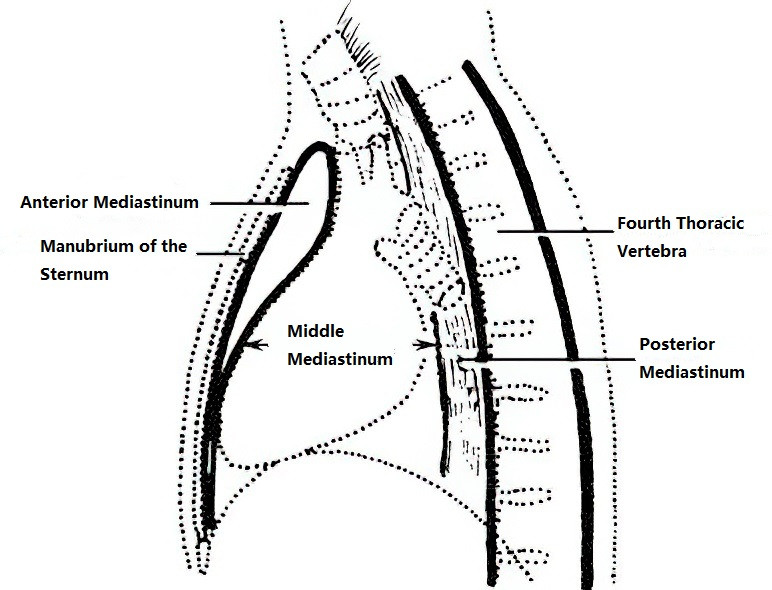

Anatomy of the Mediastinum

The mediastinum is essentially an anatomical space bordered anteriorly by the sternum, posteriorly by the thoracic vertebrae (including the paravertebral regions), laterally by the pleura, superiorly connected to the neck, and inferiorly ending at the diaphragm. It contains the heart, major blood vessels, esophagus, trachea, nerves, thymus, thoracic duct, abundant lymphatic tissue, and fatty tissue. For the purpose of localizing mediastinal pathologies, the mediastinum is typically divided into sections. The most common clinical division is the "four-region method," which uses an imaginary horizontal line connecting the sternal angle to the inferior border of the fourth thoracic vertebra to divide the mediastinum into superior and inferior portions. The inferior mediastinum is further subdivided into anterior, middle, and posterior compartments by the anterior and posterior borders of the pericardium.

Figure 1 Clinical anatomical division of the mediastinum

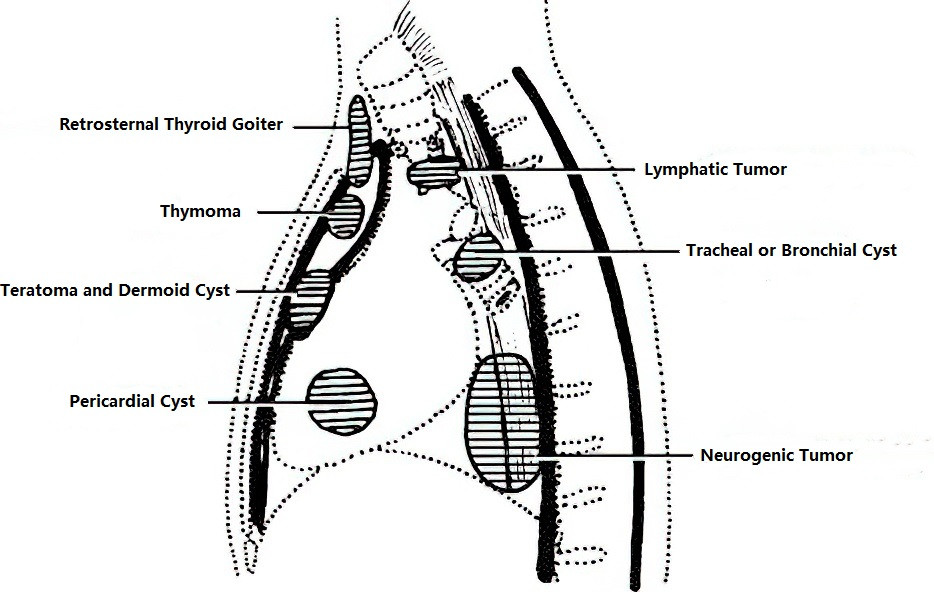

Characteristics of Mediastinal Tumors

Mediastinal tumors refer to neoplasms or cysts located in the mediastinal region. Due to the complexity of embryological origins and the diversity of structures in the mediastinum, mediastinal tumors may include a wide range of types, both primary and secondary. Among primary tumors, benign lesions are more common, though a significant proportion are malignant.

Figure 2 Common locations of mediastinal tumors

Symptoms vary based on the type, location, and size of the tumor. Common clinical features include:

- Respiratory symptoms: These include chest tightness, chest pain, coughing, and hemoptysis.

- Neurological symptoms: These may involve symptoms such as hiccups or diaphragmatic paralysis caused by involvement of the phrenic nerve. Compression of the sympathetic trunk can result in Horner's syndrome, compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve can cause hoarseness, and involvement of the brachial plexus can lead to numbness in the upper limb, pain in the scapular region, and radiating pain to the upper extremities. Occasionally, dumbbell-shaped neurogenic tumors can compress the spinal cord, causing paraplegia.

- Infectious symptoms: These may arise when cyst rupture or tumor infection affects the bronchus or lung tissue, leading to signs of infection.

- Compression symptoms: For example, compression of the brachiocephalic vein can cause increased venous pressure in one upper limb and neck; compression of the superior vena cava can result in superior vena cava syndrome, presenting as swelling and cyanosis of the face and upper limbs, distension of the superficial neck veins, and tortuous veins on the chest wall. Esophageal compression can lead to dysphagia.

- Specific symptoms: These include mobility of substernal thyroid goiters with swallowing, teratomas rupturing into the bronchus causing expectoration of sebaceous material and hair, bronchogenic cysts communicating with the bronchus manifesting as bronchopleural fistula, and thymomas accompanied by myasthenia gravis.

Diagnosis of Mediastinal Tumors

The diagnosis typically relies on imaging techniques and pathological examination. Imaging modalities such as chest CT, MRI, and ultrasound can provide preliminary information about the tumor's location, size, and relationship with surrounding structures. Pathological confirmation is achieved through biopsy or surgical resection of the tumor. Differentiation can also be aided by procedures like bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, and mediastinoscopy when needed.

Treatment of Mediastinal Tumors

Treatment depends on factors such as tumor type, location, size, and relationship to adjacent structures. For benign tumors, surgical resection is the primary treatment approach. For malignant tumors, multimodal treatment strategies that include surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy are determined based on the individual case. Surgical options range from open thoracotomy to minimally invasive thoracoscopic approaches. Overall, treatment plans for mediastinal tumors require careful consideration of multiple factors.

Thymic Tumors

Thymomas

Thymomas are tumors originating from thymic epithelium, often occurring in the anterior superior mediastinum. Macroscopically, thymomas are typically round or oval with variable sizes and textures, ranging from soft to firm, and are usually deep brown or gray-red in color. Most thymomas have well-defined borders, though some may invasively affect adjacent tissues and organs. Clinically, around 15% of patients with thymomas are associated with myasthenia gravis. Conversely, more than half of patients with myasthenia gravis exhibit thymomas or thymic hyperplasia. Occasionally, remnants of atrophic thymic tissue contain active germinal centers that may be ectopically located in fatty tissues near the trachea, thyroid, pulmonary hilum, pericardium, or diaphragm.

Due to the thymus' role in immune function, some thymic disorders may be linked to autoimmune mechanisms. Early-stage thymomas may present without symptoms and are often discovered incidentally during routine examinations. Common clinical symptoms include dull chest pain, shortness of breath, and coughing. Thymomas may locally invade or metastasize distantly, and recurrence is possible even after complete resection. However, thymomas are considered tumors with relatively low biological malignancy, and early treatment is associated with favorable outcomes.

Thymic Carcinomas

Both thymic carcinomas and thymomas originate from thymic epithelium. Thymic carcinomas are primarily squamous cell carcinomas but may include other subtypes. Their malignant potential is higher than that of thymomas, and they often exhibit aggressive growth patterns.

WHO Classification

Based on the WHO classification, thymomas are divided into type A, type AB, and type B. Type A, also known as medullary type, predominantly consists of spindle or oval-shaped tumor cells and has few non-neoplastic lymphocytes. Type AB features localized foci resembling type A alongside lymphocyte-rich foci. Type B is further categorized into three subtypes:

- B1: Lymphocyte-rich thymoma.

- B2: Thymoma with epithelial tumor cells interspersed within a lymphocyte-rich background.

- B3: Comprised of round or polygonal epithelial cells with moderate atypia, mixed with lymphocytes and areas of squamous metaplasia.

The updated WHO classification has excluded thymic carcinoma from the thymoma category, and thymic carcinoma is no longer referred to as type C thymoma.

Staging of Thymomas

Thymoma staging includes Masaoka staging and TNM staging. Both systems are currently used in clinical settings, though the Masaoka staging system has been more commonly applied historically. Tumor staging is based on the extent of invasion, whether surrounding tissues or organs are affected, and the presence of distant metastasis. The four stages of the Masaoka system are as follows:

- Stage I: Tumor confined to the thymus without capsule invasion.

- Stage II: Tumor invades the capsule or mediastinal fat tissue.

- Stage III: Tumor invades the pericardium, major blood vessels, or lung parenchyma.

- Stage IV: Presence of distant metastasis.

Treatment and Prognosis of Thymomas

Surgery remains the primary treatment modality for thymomas. Stage I thymomas are generally curable with complete surgical resection, with a 5-year survival rate of 94.3%. For all patients undergoing surgical resection, the overall 5-year survival rate is also high at 78%. Stage II thymomas have a 5-year survival rate of 86.3% and a 10-year survival rate of 75.4% following surgery. However, for stage III and IV thymomas, the likelihood of achieving complete resection decreases, with 5-year survival rates dropping to 71.6% and 39.4%, respectively, and 10-year survival rates decreasing to 56.6% and 29.6%, respectively. Advanced cases often require a combination of therapies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy. The main prognostic factors affecting long-term survival include the completeness of surgical resection and Masaoka staging.

Neurogenic Tumors

Neurogenic tumors often originate from the sympathetic nervous system, with a smaller proportion arising from the peripheral nerves. These tumors are frequently located in the paravertebral costovertebral region of the posterior mediastinum, usually presenting unilaterally. Smaller tumors are typically asymptomatic, whereas larger ones may compress nerve trunks, and malignancy or invasive growth can lead to pain. Mediastinal neurogenic tumors are broadly divided into two categories:

Autonomic Nervous System Tumors

Most originate from the sympathetic nervous system. Malignant types include neuroblastomas and ganglioneuroblastomas, while benign types include ganglioneuromas. A small number of neurofibromas arise from the vagus nerve.

Peripheral Nerve Tumors

Benign types include schwannomas and neurofibromas, which commonly occur in spinal nerve roots or their proximal segments, though some originate from intercostal nerves. Malignant types include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibrosarcomas.

Teratomas and Dermoid Cysts

Teratomas and dermoid cysts are most often located in the anterior mediastinum, in front of the great vessels at the base of the heart. Based on their embryonic origin, they can be categorized into epidermoid cysts, dermoid cysts, and teratomas (consisting of tissues from the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). However, their developmental mechanisms are shared. Teratomas are usually solid tumors containing cysts of varying sizes and numbers. The cyst walls often exhibit calcifications and contain connective tissue, as well as epidermis, dermis, and sebaceous glands. The cyst fluid is usually yellowish-brown, mixed with sebaceous material and cholesterol nodules, and may contain hair. Solid components can include bone, cartilage, muscle, bronchial, intestinal, and lymphoid tissues. Approximately 10% of teratomatous tumors are malignant.

Mediastinal Cysts

Common types of mediastinal cysts include bronchogenic cysts, esophageal cysts (sometimes referred to as foregut cysts or enteric cysts), and pericardial cysts. These cysts arise from ectopic embryonic tissue during development. All three belong to the category of benign tumors, typically appearing round or oval with thin walls and well-defined margins.

Intrathoracic Ectopic Tissue Tumors and Lymphatic Tumors

Intrathoracic ectopic tissue tumors include retrosternal thyroid goiters and parathyroid adenomas. Lymphatic tumors, often malignant, include lymphomas. These tumors typically present as bilateral or irregular masses. Lymphatic tumors are usually not suitable for surgical resection and are instead treated with radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

Other Tumors

Less common mediastinal tumors include those of vascular origin, fatty tissue, connective tissue, or mesenchymal tissue originating from muscle.