Esophageal cancer (esophageal carcinoma or carcinoma of the esophagus) is a common malignant tumor of the upper gastrointestinal tract and is currently ranked as the eighth most common cancer globally.

Epidemiology and Etiology

The incidence and mortality rates of esophageal cancer vary significantly across countries. In Western countries, the incidence is relatively low, approximately 2–5 per 100,000 population, with adenocarcinoma as the predominant pathological type. In Asia, the incidence is higher, approximately 12–32 per 100,000 population, with squamous cell carcinoma being the primary type. The disease is more common in males than females, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 13–27:1. The majority of cases occur in individuals over the age of 40, with the highest incidence observed in the age group of 60–64.

The exact cause of esophageal cancer remains unclear, but smoking and heavy alcohol consumption are well-established risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is often associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett's esophagus. Studies have shown that smokers have a 3–8 times higher risk of developing esophageal cancer, while alcohol consumers have a 7–50 times higher risk. Other major carcinogenic risk factors include nitrosamines, certain fungi, and their toxins. Additional possible etiological factors include:

- Deficiencies in certain trace elements and vitamins.

- Poor dietary habits, such as consuming hard or excessively hot food and eating too quickly.

- Genetic predisposition to esophageal cancer.

In conclusion, the etiology of esophageal cancer is complex and multifactorial. Some factors may be primary causes, others may act as triggers, and some may merely represent correlating phenomena. Further in-depth research is needed in this area.

Pathology

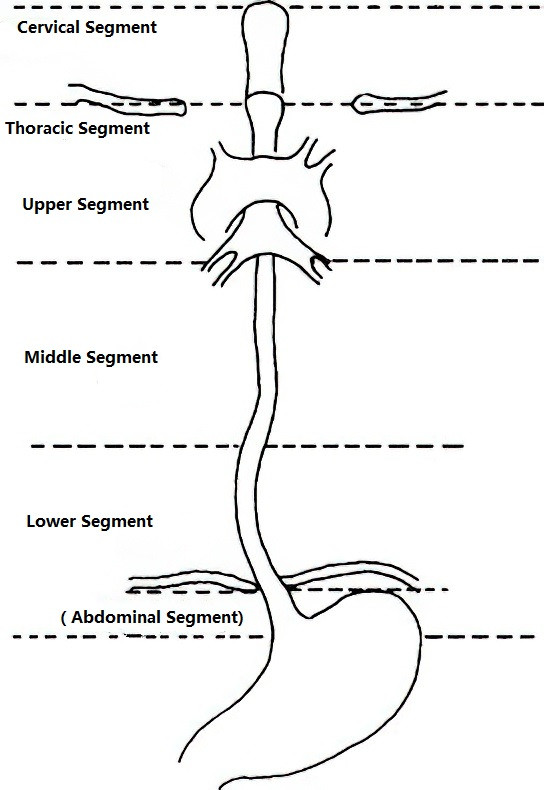

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) classify the esophagus into different segments for staging (8th Edition). The classification is based on the location of the primary tumor's center:

- Cervical segment: Extends from the esophageal inlet (at the level of the cricoid cartilage) to the sternal notch, approximately 20 cm from the incisors.

- Thoracic segment: Extends from the sternal notch to the upper margin of the esophageal hiatus, approximately 25 cm in length, further divided into upper, middle, and lower sections:

- Upper thoracic segment: From the sternal notch to the lower border of the azygos vein arch, approximately 25 cm from the incisors.

- Middle thoracic segment: From the lower border of the azygos vein arch to the lower border of the inferior pulmonary vein, approximately 30 cm from the incisors.

- Lower thoracic segment: From the lower border of the inferior pulmonary vein to the upper margin of the esophageal hiatus, approximately 40 cm from the incisors.

- Abdominal segment: Extends from the upper margin of the esophageal hiatus to the gastroesophageal junction, approximately 42 cm from the incisors.

Figure 1 Segments of the esophagus

Middle thoracic esophageal cancer is the most common, followed by the lower thoracic segment, with the upper segment being the least frequent. In high-incidence areas, squamous cell carcinoma accounts for over 80% of cases, while in low-incidence areas, adenocarcinoma accounts for over 70%.

Early-stage lesions are typically confined to the mucosa (carcinoma in situ), presenting as mucosal hyperemia, erosion, plaques, or papillary-like growths, and rarely form tumors. In the middle and late stages, the tumor grows larger and encircles the esophagus, protrudes into the lumen, and may penetrate the full thickness of the esophageal wall to invade the mediastinum, pericardium, trachea, bronchi, or aorta.

Based on pathological morphology, advanced esophageal cancer can be classified into four types:

- Medullary Type: The esophageal wall thickens significantly and expands both inward and outward, with sloped, raised margins at the upper and lower ends of the tumor. It often involves the entire or most of the esophageal circumference.

- Fungating Type: The tumor protrudes into the lumen in a mushroom-like shape with raised margins. The surface of the tumor often has superficial ulcers with an uneven base.

- Ulcerative Type: The tumor forms a deeply sunken ulcer with distinct margins. The size and shape of the ulcer vary, extending into the muscular layer, but obstruction is relatively mild.

- Stenotic Type: The tumor causes significant annular narrowing, affecting the entire esophageal circumference and leading to early onset of obstructive symptoms.

Spread and Metastasis

The tumor initially spreads toward the submucosal layer and then infiltrates upward, downward, and through the full thickness of the esophageal wall, easily penetrating the loose adventitia to invade adjacent organs. Metastasis primarily occurs via lymphatic routes, first involving the submucosal lymphatic vessels and then spreading through the muscular layer to regional lymph nodes corresponding to the tumor's location.

Cervical esophageal cancer may metastasize to retropharyngeal, deep cervical, and supraclavicular lymph nodes.

Thoracic esophageal cancer may metastasize to paraesophageal lymph nodes, mediastinal apex lymph nodes, diaphragmatic, pericardial, gastric, tracheobronchial, carinal, and hilar lymph nodes. Hematogenous metastasis occurs later in the disease.

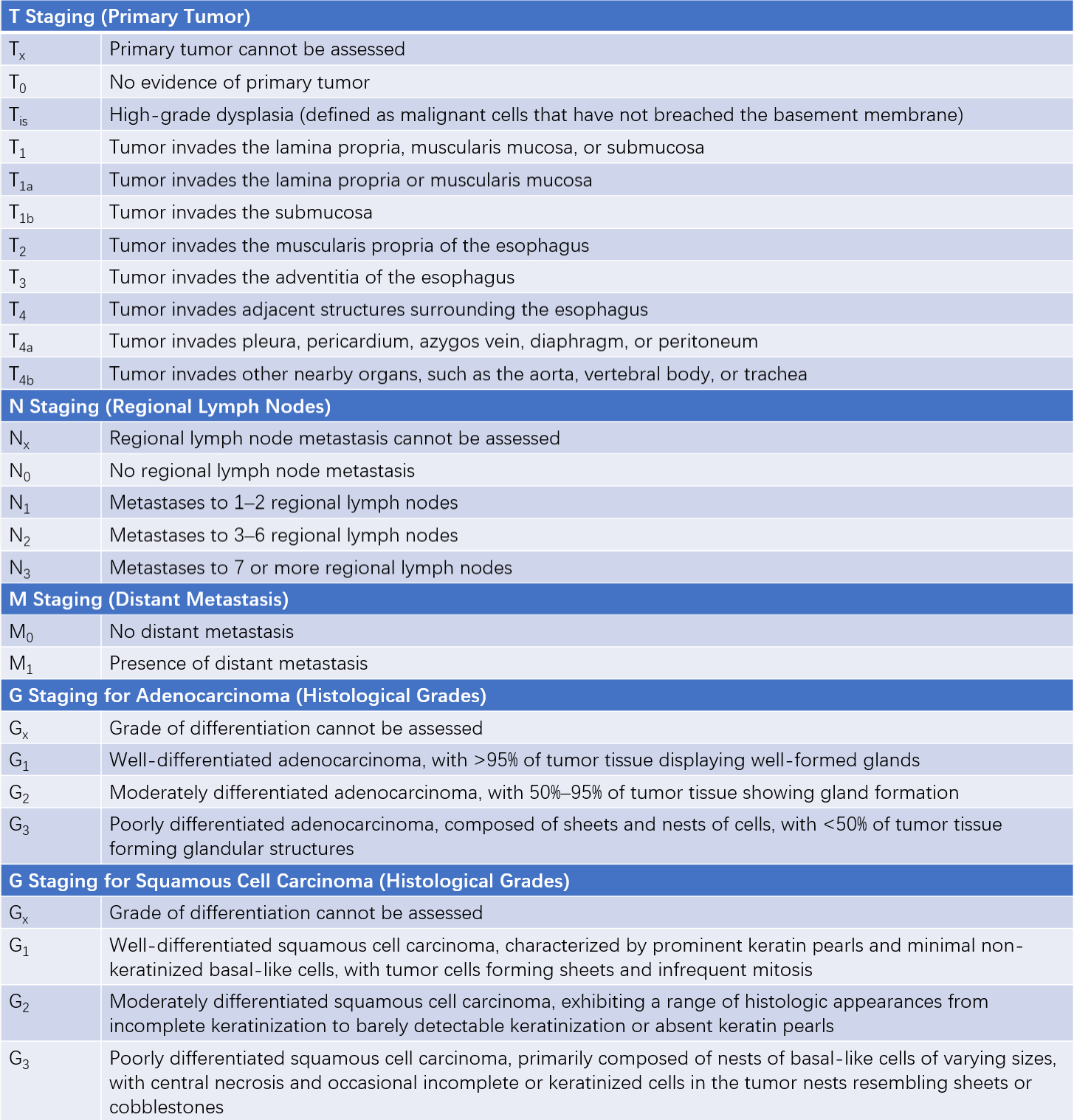

The TNM staging system for esophageal cancer by the AJCC and UICC (8th Edition) is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 International TNM staging system for esophageal cancer (8th edition by AJCC/UICC, 2017)

Clinically, T1aN0M0 stage esophageal cancer is classified as early esophageal cancer. When the primary tumor invades the local anatomical structures of the esophagus or regional lymph nodes but no distant metastasis is observed (T2-4NanyM0 or TanyN1-3M0), it is classified as locally advanced/progressive esophageal cancer.

Clinical Manifestations

Early-stage esophageal cancer typically presents with minimal or non-specific symptoms. Patients may occasionally experience mild discomfort when swallowing coarse or hard food, such as burning, pricking, or pulling friction-like pain behind the sternum. Food may pass through the esophagus slowly, accompanied by sensations of stagnation or a foreign body. The feeling of choking or food stagnation is often relieved after swallowing water. Symptoms tend to fluctuate in severity and progress gradually.

In mid-to-late stages, progressive dysphagia becomes the hallmark symptom. Initially, swallowing solid food becomes difficult, followed by semi-solid food, and eventually even liquid food cannot be swallowed. Patients may experience gradual weight loss, dehydration, and fatigue. Persistent chest or back pain may indicate tumor invasion into adjacent structures. When inflammatory edema caused by tumor obstruction temporarily subsides or parts of the tumor slough off, obstructive symptoms can temporarily improve, which may give a false impression of recovery.

Esophageal cancer can also invade surrounding organs and tissues, leading to various symptoms, such as hoarseness due to involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, Horner syndrome resulting from invasion or compression of the cervical sympathetic ganglia, and severe coughing when swallowing water or food due to esophageal-tracheal fistula caused by tracheal or bronchial invasion. Long-term inability to eat normally can ultimately result in cachexia. Metastases to organs such as the liver or brain may lead to corresponding symptoms.

During physical examinations, particular attention should be paid to signs of distant metastases, such as enlarged supraclavicular lymph nodes, palpable liver masses, ascites, and pleural effusion.

Diagnosis

For suspected cases, a barium double-contrast esophagography can be performed. Early findings may include:

- Disruption, coarse texture, or irregularity of esophageal mucosal folds.

- Small filling defects.

- Localized rigidity and interrupted peristalsis of the esophageal wall.

- Small niches.

In mid-to-late stages, significant irregular narrowing and large filling defects are observed, accompanied by rigid esophageal walls. Additionally, varying degrees of esophageal dilation may be present above the site of narrowing.

Endoscopic examination can reveal intraluminal esophageal masses, and biopsy of the lesion can provide a definitive diagnosis. However, early-stage esophageal cancer often evades detection. Techniques such as chromoendoscopy, magnifying endoscopy, and electronic staining endoscopy have recently been used for more precise evaluations.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) allows for the assessment of the depth of esophageal cancer invasion and mediastinal lymph node involvement, aiding in preoperative T and N staging. Chest and abdominal CT scans, MRI of the brain, and bone scans are utilized to evaluate local invasion and distant metastases, serving as important tools for N and M staging.

Differential Diagnosis

Esophageal cancer must be differentiated from benign esophageal tumors, achalasia, and benign esophageal strictures. Relevant clinical features can be referenced from related sections. Diagnostic methods primarily rely on barium double-contrast esophagography, endoscopic examination, and esophageal manometry.

Prevention

Effective preventive measures include:

- Etiological Prevention: Modification of unhealthy lifestyle habits.

- Pathogenesis Prevention: Active management of esophageal epithelial hyperplasia and treatment of precancerous conditions, such as esophagitis, polyps, and diverticula.

- Cancer Awareness and Education: Promoting anti-cancer knowledge through public education initiatives and conducting cancer screenings and mass surveys in high-risk populations.

- Clinical Improvement: Enhancing diagnostic and treatment capabilities through standardized clinical practices.

Treatment

The treatment of esophageal cancer follows a multidisciplinary approach, incorporating surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy.

Endoscopic Treatment for Early-Stage Esophageal Cancer and Precancerous Lesions

For early-stage esophageal cancer and precancerous lesions, endoscopic treatments such as radiofrequency ablation, cryotherapy, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) may be utilized. Surgical indications must be adhered to strictly in these cases.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery remains the preferred treatment for resectable esophageal cancer. Accurate TNM staging is critical prior to surgery. The surgical approach involves complete tumor resection (with a margin of at least 5–8 cm above and below the tumor), digestive tract reconstruction, and lymphadenectomy in two fields (chest and abdomen) or three fields (neck, chest, and abdomen).

Indications

Indications for surgery:

- cT1bN0M0 stage esophageal cancer, including the cT1b-SM1 stage (invasion into the upper one-third of the submucosal layer), is recommended for direct curative surgery.

- All cases of locally advanced/progressive esophageal cancer should undergo multidisciplinary evaluation prior to surgery to devise a comprehensive perioperative treatment plan. Neoadjuvant therapy (chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy alone) is commonly performed before surgery, followed by surgical treatment.

Contraindications

Contraindications for surgery:

- Stage IV and certain Stage III esophageal cancer cases, such as T4 tumors invading the aorta or trachea.

- Severe cardiopulmonary dysfunction or concurrent serious diseases of other vital organ systems that make surgery intolerable.

Surgical Approaches

Various surgical approaches include left thoracotomy alone, combined right thoracic and abdominal incisions, three-field incisions (neck, chest, and abdomen), or combined thoracoabdominal incisions. Alternatives such as transhiatal blunt esophageal resection without thoracotomy may also be employed. A two-field or three-field approach via the right chest is currently recommended in clinical practice as it aligns better with oncological principles.

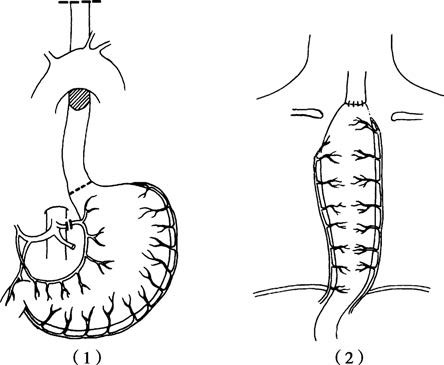

Figure 2 Postoperative gastroesophageal reconstruction following esophageal cancer resection

1, Resected area for esophageal cancer in the upper and middle segments of the esophagus.

2, Stomach replacement of the esophagus with cervical anastomosis.

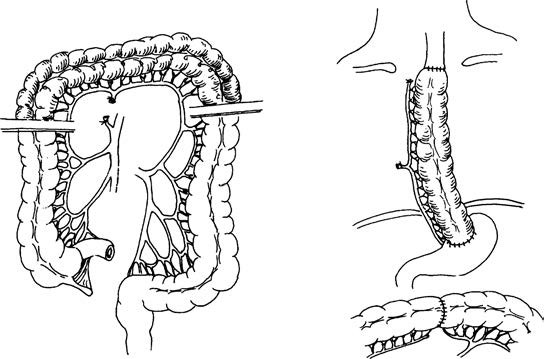

Figure 3 Colon interposition for esophageal replacement

Transverse colon used as a substitute for the esophagus.

Digestive tract reconstruction methods depend on the location of the esophageal cancer. For cancers in the lower esophagus, the anastomotic site is typically above the aortic arch, while for cancers in the middle or upper esophagus, the cervical region is preferred for anastomosis. Common options for esophageal replacement include the stomach, although the colon or jejunum may be used based on individual patient conditions. Minimally invasive techniques, such as thoracoscopic or laparoscopic surgery, are widely employed in esophageal cancer treatment. The choice of surgical approach depends on the patient's condition and tumor location.

Palliative Procedures

For patients with advanced esophageal cancer who are not candidates for curative surgery, palliative procedures such as esophageal stenting or gastrostomy may be performed to improve quality of life.

Surgical Outcomes

The resection rate for esophageal cancer is 58%–92%, with postoperative complication rates of 6.3%–20.5%. Anastomotic leakage is one of the most serious postoperative complications, with others including anastomotic strictures, chylothorax, and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. The 5-year and 10-year survival rates after surgery are 8%–30% and 5.2%–24%, respectively.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy plays an important role in the treatment of esophageal cancer, offering tumor size reduction and symptom relief.

- Preoperative Radiotherapy: Improves surgical resection rates and enhances long-term survival. Surgery is generally performed 2–3 weeks after radiotherapy concludes.

- Postoperative Radiotherapy: Begins 3–6 weeks after surgery for residual cancer tissue identified during the procedure.

- Definitive Radiotherapy: Commonly used for cancers in the cervical or upper thoracic esophagus or for patients with contraindications to surgery who can tolerate radiation. Three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy is an advanced technique currently in use.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy for esophageal cancer includes palliative chemotherapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (preoperative), and adjuvant chemotherapy (postoperative). Treatment regimens must emphasize standardization and individualization. Combining chemotherapy with surgery or radiotherapy as part of a comprehensive treatment strategy may improve efficacy, alleviate symptoms, and extend survival.

Combined Chemoradiotherapy

Concurrent or sequential chemoradiotherapy is an option for patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer without distant metastases. Treatment response is reassessed to determine whether to proceed with surgical treatment or continue with definitive chemoradiotherapy.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has emerged as a promising new therapeutic option for esophageal cancer in recent years, yielding significant advances. It has demonstrated efficacy across all stages of esophageal cancer, not only improving survival and quality of life in patients with advanced disease but also enhancing treatment outcomes when combined with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

Follow-Up

The overall 5-year survival rate for esophageal cancer is approximately 30%. Comprehensive medical records and related documentation should be established for newly diagnosed patients, followed by regular post-treatment follow-up.