Lung cancer, also known as primary bronchogenic carcinoma, refers to malignant tumors originating from the bronchial epithelium or alveolar epithelium. In recent years, the incidence of lung cancer has significantly increased worldwide. In industrially developed countries, lung cancer has become the leading cancer among males. By the end of the 20th century, lung cancer emerged as the primary cause of death from malignant tumors. Most cases of lung cancer occur in individuals over the age of 40, with men being more commonly affected, although the incidence among women has shown a marked increase in recent years.

Etiology

The exact causes of lung cancer remain unclear. Risk factors for lung cancer include smoking, air pollution, exposure to cooking oil fumes, occupational exposure (involving substances such as arsenic, cadmium, chromium, nickel, asbestos, coal during coking processes, radon, and ionizing radiation), a history of chronic lung diseases, genetic susceptibility, and gene mutations. Prolonged and heavy smoking is the most significant risk factor for lung cancer, with higher risk associated with greater smoking intensity, earlier smoking initiation, and longer smoking duration.

Pathology

Lung cancer originates from the bronchial epithelium or alveolar epithelium. The disease occurs more frequently in the right lung than in the left, and in the upper lobes more than the lower lobes. Lung cancer arising near the openings of segmental bronchi, closer to the hilum, is termed central lung cancer. Conversely, cancer originating beyond the segmental bronchial openings and located in the peripheral parts of the lung is referred to as peripheral lung cancer.

Lung cancer is generally classified into two major categories: small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Due to substantial differences in biological behavior, treatment, and prognosis, cancers other than small cell lung cancer are collectively termed non-small cell lung cancer. The current pathological classification of lung cancer follows the 2021 WHO revised criteria. The most common pathological subtypes of lung cancer include:

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Closely associated with smoking, it predominantly occurs in males. It typically originates from larger bronchi and is mostly classified as central lung cancer. Squamous carcinoma exhibits varying degrees of differentiation, grows relatively slowly, and has a long disease course. Central necrosis within larger tumors can lead to the formation of thick-walled cavities. It generally metastasizes first through lymphatic spread, with hematogenous spread occurring relatively late.

Adenocarcinoma

The incidence of adenocarcinoma has risen significantly in recent years, surpassing squamous carcinoma to become the most common type of lung cancer. It tends to occur at a younger age compared to squamous carcinoma and small cell lung cancer. Adenocarcinoma is more commonly seen in peripheral lung regions and generally grows slowly. However, hematogenous and lymphatic metastases can occur even when the tumor is relatively small.

Small Cell Carcinoma

Strongly associated with smoking, it is more commonly seen in elderly males and central lung regions. Small cell carcinoma originates from neuroendocrine cells, exhibits high malignancy, and grows rapidly. Early involvement of lymphatic and hematogenous systems is common. Although it is relatively sensitive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, resistance or recurrence develops quickly, resulting in poor prognosis.

Some tumors may exhibit mixed histological types, such as adenocarcinoma coexisting with squamous carcinoma, or non-small cell and small cell carcinomas occurring simultaneously.

Spread and Metastasis

Direct Invasion

The tumor may grow along the bronchial wall and invade the bronchial lumen, leading to partial or total obstruction. It may traverse lobar fissures and infiltrate adjacent lobes. Lung cancer can penetrate the visceral pleura, resulting in pleural cavity implantation metastases, or directly invade the chest wall, mediastinal tissues, and neighboring organs.

Lymphatic Spread

Lymphatic metastasis is a common route of dissemination, particularly in small cell carcinoma and squamous carcinoma. Tumor cells spread through the lymphatics surrounding the bronchi and pulmonary vessels, initially invading the lymph nodes around the affected bronchopulmonary segment or lobe. Subsequently, metastasis progresses to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes and, eventually, to the supraclavicular and cervical lymph nodes. Lymphatic metastases in the mediastinal and supraclavicular regions typically occur on the same side as the primary lesion but may also involve the contralateral side, a phenomenon termed cross or contralateral metastasis. Mediastinal lymph node involvement without prior hilar or intrapulmonary lymph node metastasis, referred to as skip metastasis, may also be observed in lung cancer.

Hematogenous Metastasis

Hematogenous spread occurs more frequently in small cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma than in squamous carcinoma. The most common distant metastasis sites for lung cancer include the bones, brain, liver, and adrenal glands.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of lung cancer are closely related to the tumor’s location, size, compression or invasion of adjacent organs, and the presence or absence of metastasis.

Early-Stage Symptoms

Early-stage lung cancer, especially peripheral lung cancer, is often asymptomatic and is usually detected through chest X-ray or CT scans. As the tumor progresses, various symptoms may appear. Common clinical symptoms include cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, fever, and shortness of breath. The most prevalent symptom is cough. Tumors located in larger bronchi are often associated with irritative coughing. Tumor growth leading to bronchial obstruction may result in secondary atelectasis and pulmonary infections, with an increased volume of sputum that may be purulent. Hemoptysis is more frequently observed in central lung cancer, typically presenting as blood-streaked sputum, small streaks, or intermittent mild bleeding, though massive hemoptysis is rare.

Symptoms of lung cancer are nonspecific. Respiratory symptoms persisting for more than two weeks, especially hemoptysis, dry cough, or any changes in preexisting respiratory symptoms, warrant consideration of lung cancer.

Symptoms of Locally Advanced Disease

Locally advanced lung cancer may produce symptoms and signs due to compression or invasion of adjacent organs:

- Phrenic nerve involvement may cause ipsilateral diaphragmatic paralysis.

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve compression or invasion may lead to vocal cord paralysis and hoarseness.

- Superior vena cava syndrome may develop due to compression of the superior vena cava, resulting in visible distension of veins in the face, neck, upper chest, and arms, along with subcutaneous edema.

- Pleural cavity implantation may lead to pleural effusion, often hemorrhagic, causing shortness of breath. Tumor infiltration of the pleura and chest wall may result in persistent, severe chest pain.

- Mediastinal invasion with esophageal compression may cause dysphagia.

- Pancoast tumor, also referred to as an apical lung tumor, involves the thoracic inlet, leading to compression of nearby structures such as the first rib, subclavian vessels, brachial plexus, and cervical sympathetic nerves. Manifestations include severe chest and shoulder pain, venous distension and edema in the upper limbs, arm pain, motor dysfunction in the upper limbs, ptosis of the ipsilateral upper eyelid, pupil constriction, enophthalmos, and absent sweating on the affected side of the face (Horner syndrome).

Symptoms of Distant Metastasis

The clinical manifestations of distant metastasis depend on the invaded organ:

- Brain metastases may result in headache, nausea, or other neurological symptoms and signs.

- Bone metastases may cause bone pain and elevations in blood alkaline phosphatase or calcium.

- Liver metastases may lead to hepatomegaly and increases in alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase, or bilirubin.

- Subcutaneous metastases may present as palpable nodules under the skin.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

A small number of lung cancer cases exhibit paraneoplastic syndromes, where tumors produce endocrine substances that cause non-metastatic systemic symptoms. Examples include hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (clubbing of fingers, joint pain, and periosteal proliferation), Cushing's syndrome, Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, gynecomastia in males, and polymyositis or polyneuropathy. These symptoms may resolve following the surgical resection of the lung cancer.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is critically important, as early detection and treatment of lung cancer provide better therapeutic outcomes.

Imaging Techniques

Chest X-ray

Chest X-ray is a commonly used diagnostic tool for identifying lung lesions. Early lung cancer may not display any abnormalities on chest X-rays. When a tumor obstructs a bronchus, signs of pneumonia may be observed in the affected lobe or segment. Complete bronchial obstruction by a tumor may result in atelectasis of the corresponding lung lobe or even an entire lung. Hilar and mediastinal lymph node metastases may appear as hilar opacities or widened mediastinal opacities. The upper lobe of the lung combined with a hilar mass may form the characteristic "reverse S sign." Compression of the phrenic nerve due to mediastinal lymphadenopathy may cause diaphragmatic elevation, and abnormal diaphragmatic motion may be observed via fluoroscopy. Enlarged metastatic lymph nodes beneath the carina may widen the angle of tracheal bifurcation. Late-stage cases may exhibit pleural effusion or rib destruction.

Chest CT

CT scans can detect lesions in areas that are typically hidden on routine X-rays, such as the lung apices, perispinal regions, retrocardiac space, and mediastinum. Thin-slice CT offers high resolution and enables the detection of smaller lesions with lower density. CT not only provides local imaging details of lesions but also evaluates tumor extent, relationships with adjacent organs, and lymph node involvement. This information is crucial for developing treatment plans for lung cancer.

Low-dose chest CT is currently the most effective screening tool for lung cancer. It facilitates early detection, diagnosis, and treatment, thereby reducing lung cancer mortality rates. Common CT findings of lung cancer include lobulation, spiculations, cavitation, air bronchograms, tumor-feeding arteries, vascular notching and convergence, pleural retraction, and eccentric thick-walled cavities. Some early adenocarcinomas appear as ground-glass opacities (GGO) on CT. Central lung cancers may appear as hilar masses and exhibit features such as endobronchial lesions, luminal narrowing or obstruction, and bronchial wall thickening, accompanied by hilar enlargement, obstructive pneumonia, or atelectasis.

PET

PET imaging distinguishes normal cells from tumor cells based on differential uptake of radiolabeled fluorodeoxyglucose. It is utilized for the differential diagnosis of pulmonary nodules, cancer staging, detection of metastatic lesions, evaluation of treatment response, and monitoring for tumor recurrence or metastasis. PET-CT, combining the imaging benefits of PET and CT, enhances diagnostic accuracy and efficacy by addressing the challenge of precise lesion localization in PET scans.

MRI

MRI is not routinely used for the diagnosis of lung cancer, but it offers more detailed information regarding chest wall invasion and involvement of the subclavian vessels or brachial plexus in cases of Pancoast tumors. It can also serve as an alternative imaging modality for patients who are allergic to iodine and cannot undergo contrast-enhanced CT.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound plays an important role in staging lung cancer. In addition to abdominal ultrasound (primarily for the liver and adrenal glands), it is a useful auxiliary tool for locating pleural effusions and assessing supraclavicular lymph node metastasis.

Bone Scan

Bone scans using 99mTc-labeled bisphosphonates are an essential method for screening bone metastases in lung cancer patients.

Examinations Aiding Pathological Diagnosis

Sputum Cytology

Cancer cells shed by lung tumors can be expelled through sputum and identified via cytological examination. The detection of cancer cells in sputum can confirm a diagnosis. Central lung cancer, particularly cases accompanied by hemoptysis, shows a higher likelihood of cancer cells being detected. Clinically suspected cases of lung cancer typically require three or more consecutive sputum submissions for cytology.

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy is routinely performed in cases of suspected lung cancer. Its main objectives are:

- To observe lesions within the trachea and bronchi and obtain pathological evidence.

- To localize lesions accurately, which is useful for determining surgical resection scope and method.

- To identify other potential multiple primary cancers within the trachea.

Advances in autofluorescence bronchoscopy technology have improved detection rates for in situ or occult lung cancers that may not be visible with conventional methods.

Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration (EBUS-TBNA)

EBUS-TBNA enables fine-needle aspiration biopsy of mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes under ultrasound guidance through bronchoscopy. This technique is used to obtain pathological specimens and assess lymph node staging in lung cancer. Compared to mediastinoscopy, EBUS-TBNA is less invasive.

Mediastinoscopy

Mediastinoscopy involves a small incision made at the neck or parasternal region under general anesthesia. This allows direct visualization and biopsy of lymph nodes around the trachea or the subcarinal region to confirm lymphatic metastasis. Compared to EBUS, mediastinoscopy provides larger tissue samples with higher diagnostic accuracy.

Transthoracic Needle Aspiration (TTNA)

TTNA is used for lung lesions, particularly for peripheral masses that are difficult to diagnose through sputum cytology or bronchoscopy. Performed under CT or ultrasound guidance, TTNA involves percutaneous needle aspiration for tissue biopsy. Potential risks include pneumothorax and bleeding. However, with the use of protective needle sheaths, the risk of needle tract implantation metastasis is extremely low. TTNA may obtain pathological confirmation before surgery or for patients without surgical indications, aiding in the formulation of radiotherapy or chemotherapy plans.

Evaluation of Pleural Effusion

In cases of suspected pleural effusion caused by lung cancer metastasis, pleural fluid can be aspirated, and smear tests performed to search for cancer cells.

Biopsy of Metastatic Lesions

Suspicious metastatic lesions in superficial lymph nodes (e.g., supraclavicular lymph nodes) or subcutaneous nodules can be biopsied either through excisional biopsy or by fine-needle aspiration to confirm the diagnosis.

Thoracoscopy

Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) may be considered in cases where other tests fail to produce a definitive diagnosis but clinical suspicion remains high. VATS provides a method to comprehensively explore the thoracic cavity, enabling biopsy of pleural lesions, diffuse lung abnormalities, small peripheral lung nodules, or hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes, which is crucial for both diagnosis and staging. Additionally, therapeutic resection may be performed concurrently.

Differential Diagnosis

Lung cancer, depending on the tumor's location, pathological type, and staging, can present various clinical manifestations and needs to be differentiated from the following diseases:

Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Tuberculoma

This condition is often confused with peripheral lung cancer. Tuberculomas are more common in younger individuals with a typically prolonged and slowly progressing clinical course. Lesions are often located in the apical-posterior segments of the upper lobes or the dorsal segments of the lower lobes. Imaging studies reveal heterogeneous densities, with sparse translucent areas and calcifications. Scattered tuberculosis foci are frequently observed elsewhere in the lungs.

Miliary Tuberculosis

This condition can resemble certain types of pulmonary adenocarcinomas. Miliary tuberculosis is usually found in young individuals and is associated with pronounced systemic toxic symptoms. Symptoms and lesions tend to improve with antituberculosis treatment.

Hilar Lymph Node Tuberculosis

This condition can manifest as a hilar mass on chest X-rays or CT scans, leading to misdiagnosis as central lung cancer. Hilar lymph node tuberculosis is more common in adolescents and is usually accompanied by symptoms of tuberculosis infection, with hemoptysis being rare.

Lung cancer and tuberculosis can coexist. Their clinical symptoms and imaging findings often overlap, leading to potential misdiagnosis and delayed early detection or treatment of lung cancer. For middle-aged and elderly tuberculosis patients, the appearance of high-density masses, atelectasis, unilateral hilar widening near existing tuberculosis lesions, or progressive lesion enlargement despite antituberculosis treatment should raise suspicion for potential lung cancer, warranting further diagnostic evaluation.

Pulmonary Infection

Bronchopneumonia

Obstructive pneumonia caused by lung cancer is often misdiagnosed as bronchopneumonia. Bronchopneumonia typically has an acute onset, with more prominent signs of infection. Imaging shows poorly demarcated patchy or spotted opacities of uneven density that are not confined to a single lung segment or lobe. Symptoms improve rapidly, and lesions resolve quickly with antibiotic treatment.

Lung Abscess

Necrosis and liquefaction in the central part of a lung cancer lesion can mimic a lung abscess on imaging. Acute lung abscess presents with significant infectious symptoms, copious purulent sputum, and CT imaging showing thin-walled, smooth cavities with fluid levels. Surrounding lung tissue or pleura often exhibits inflammatory changes. Bronchial imaging usually reveals full cavity filling, often accompanied by bronchiectasis. Cancerous cavities tend to be eccentric, have thick and irregular walls, and lack smooth inner surfaces.

Other Pulmonary Tumors

Benign Pulmonary Tumors

These include hamartomas, fibromas, and chondromas, which can sometimes be confused with peripheral lung cancer. Benign tumors are characterized by slow growth, longer disease courses, and are generally asymptomatic. Imaging often reveals a near-round mass with uniform density, sometimes with calcifications. The contour is smooth, with no lobulation typically observed.

Bronchial Adenoma

These are low-grade malignant tumors. They tend to occur earlier in life than lung cancer and have a higher incidence in females. Clinical symptoms can resemble those of lung cancer, with recurrent hemoptysis being common. Imaging findings can also resemble lung cancer. When diagnosis is inconclusive with bronchoscopy, early thoracoscopic exploration is recommended.

Inflammatory Pseudotumor

These mimic tumors caused by chronic nonspecific inflammation and are more common in young and middle-aged individuals. Patients are often asymptomatic. Imaging usually shows a well-demarcated nodular opacity, occasionally accompanied by coarse pulmonary markings extending to the hilum on the proximal side of the opacity, which is indicative of incomplete inflammation resolution.

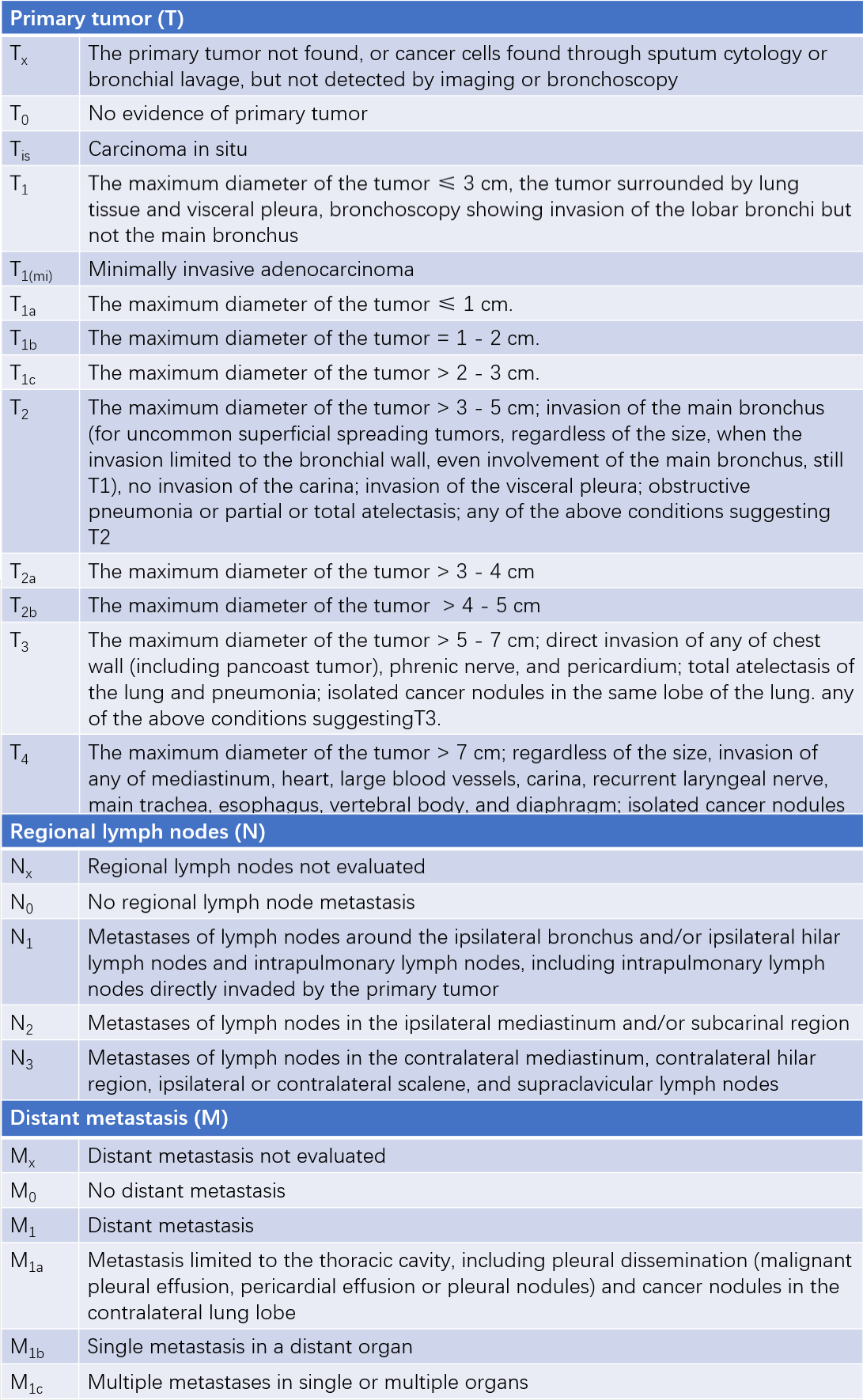

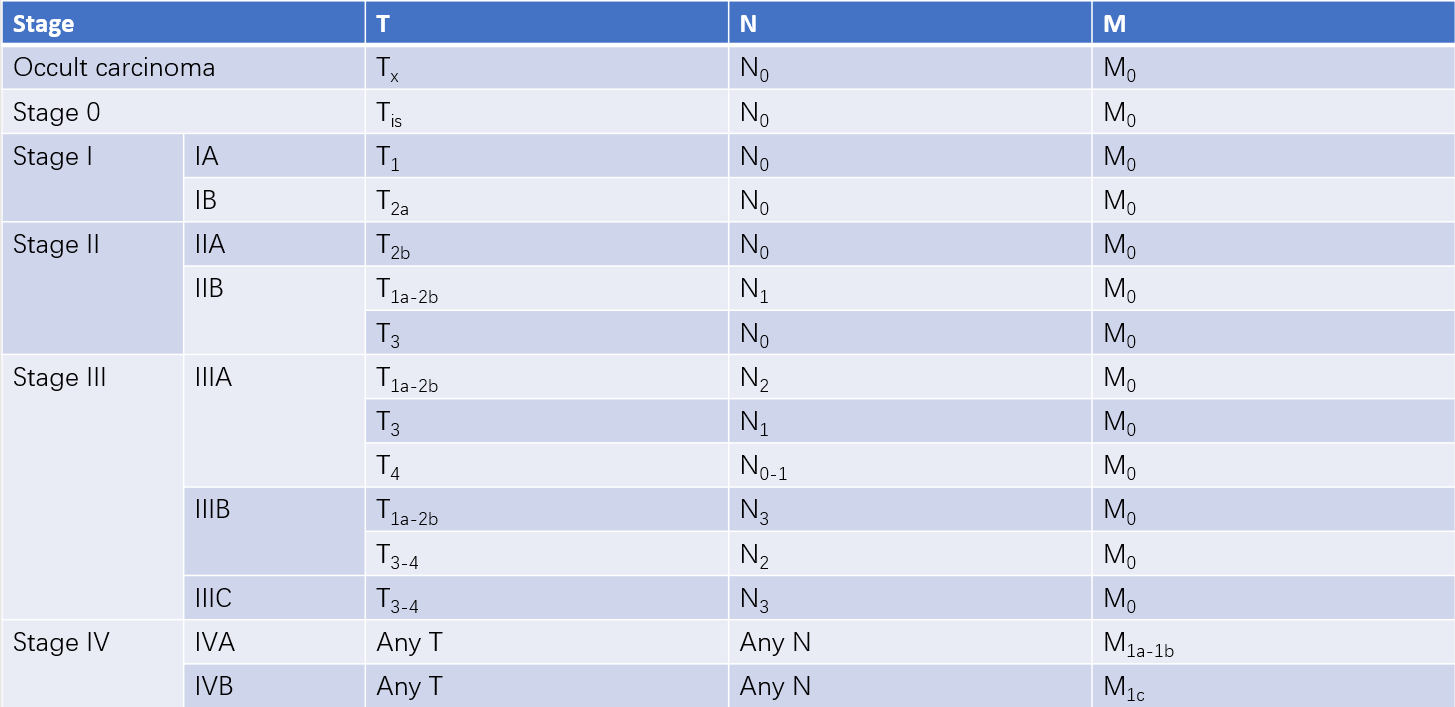

Staging

Lung cancer staging serves as a critical guide for selecting clinical treatment strategies. According to the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), lung cancer is staged using the TNM staging system, which considers tumor size and extent (T), lymph node metastasis (N), and distant metastasis (M). The 8th edition of the TNM staging system is currently used in clinical practice, applying to both non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Additionally, SCLC is often classified into "limited-stage" and "extensive-stage" categories.

Table 1 The 8th edition of the international lung cancer staging classification

The prognosis varies significantly across different stages. For NSCLC, the 5-year survival rate for stage IA ranges from 80% to 90%, whereas the 5-year survival rate for stage Ⅳ lung cancer is less than 10%.

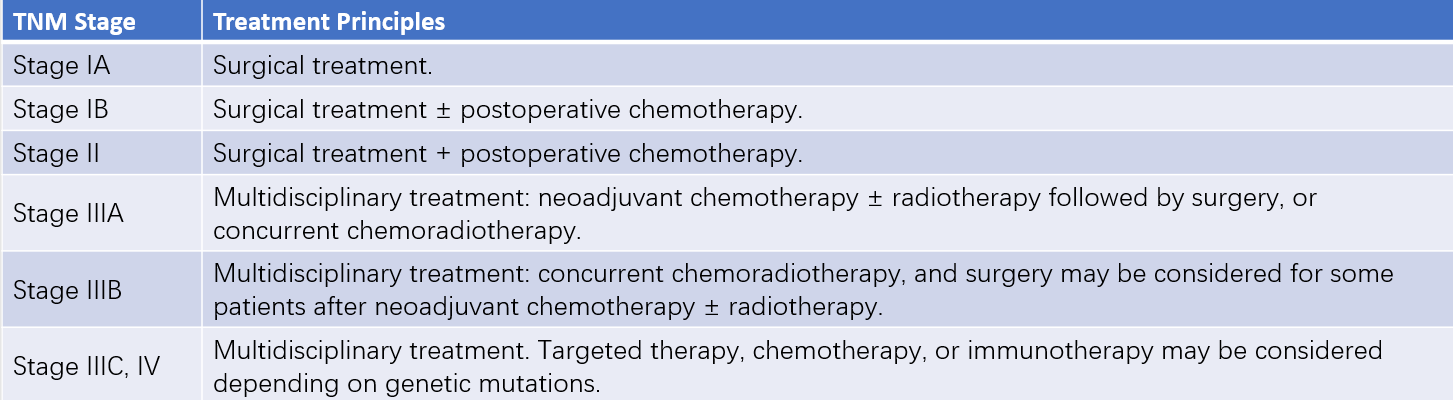

Treatment

The main treatment methods for lung cancer include surgical resection, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Treatment strategies differ greatly between small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). SCLC tends to metastasize early. Apart from early-stage cases (T1-2N0M0) where surgical resection is suitable, non-surgical treatments are generally preferred in other stages. In contrast, the treatment approach for NSCLC is determined based on the TNM stage at diagnosis.

Table 2 Treatment principles for NSCLC based on stages

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment for early-stage lung cancer often results in curative outcomes. Indications generally include stage I, stage II, and selectively chosen stage IIIA-IIIB cases (e.g., T3N1-2M0) of NSCLC. For patients with confirmed mediastinal lymph node metastasis (N2), surgery can be considered following (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. For those with stage IIIB or stage IV lung cancer, surgery is generally not regarded as the primary treatment method, except in rare cases (e.g., N2). Beyond oncological factors, patients' cardiac, pulmonary, and other vital organ functions must demonstrate sufficient reserve to tolerate surgery.

The standard surgical approach for lung cancer is anatomical lobectomy combined with lymphadenectomy. However, extended resection or limited resection may be performed depending on tumor characteristics or patient tolerability. Extended resection involves removing more than one lung lobe, such as bilobectomy, sleeve lobectomy, pulmonary artery sleeve lobectomy, pneumonectomy (complete lung removal), and procedures requiring intrapericardial vessel management or partial left atrial resection alongside pneumonectomy. The risks associated with extended resection are significantly higher than those of standard lobectomy, so patient selection for surgery should be cautious. Limited resection, including segmentectomy and wedge resection, removes less than a lobe of the lung. It has lower surgical risks but comes with a higher rate of local recurrence compared to standard lobectomy. This option is mainly reserved for very early lung cancer cases or elderly patients with poor tolerance.

Common surgical methods include conventional open thoracotomy (access via posterolateral incision or small thoracic incision) and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). VATS, performed through one to three small incisions (approximately 1–3 cm) instead of the 20–30 cm incision required in conventional open surgery, offers advantages such as minimal trauma, faster recovery, and favorable outcomes. It has become the preferred approach for surgical treatment of lung cancer.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is a form of local treatment for lung cancer. It serves as a primary treatment in cases with mediastinal lymph node metastases, where full-dose radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy is the primary treatment strategy. For patients with distant metastases, radiation therapy mainly provides symptomatic relief and serves as palliative care. For some early-stage lung cancer patients who are elderly or have significant cardiac, pulmonary, or other organ dysfunction that precludes surgery, radiation therapy is also used as a local treatment option.

Postoperative radiation therapy is utilized for cases with positive surgical margins or locally advanced disease. Among the various types of lung cancer, SCLC is most sensitive to radiation therapy, followed by squamous cell carcinoma.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy for lung cancer is categorized into neoadjuvant chemotherapy (preoperative), adjuvant chemotherapy (postoperative), and systemic chemotherapy. The standard chemotherapy regimen involves a platinum-based double-agent combination, generally using cisplatin or carboplatin. The specific regimen is chosen based on the pathological type and the patient's overall condition. Adjuvant chemotherapy is typically administered in four cycles.

Targeted Therapy

Currently, the most widely used targets in lung cancer targeted therapy include epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). In East Asian patients with lung adenocarcinoma, particularly among non-smoking females, the EGFR mutation rate exceeds 50%, making it the most significant therapeutic target.

Immunotherapy

In clinical practice, immunotherapy primarily involves monoclonal antibodies targeting the programmed death-1 (PD-1) protein and its ligand (PD-L1) pathway. These drugs restore suppressed immune responses caused by lung cancer cells expressing PD-L1, enabling a specific immune-mediated attack on the tumor. Some advanced-stage patients have achieved long-term survival through immunotherapy.

Though various treatment modalities for lung cancer are available, none offer fully satisfactory outcomes. The specific treatment plan must be determined through a multidisciplinary evaluation of lung cancer pathology, TNM staging, the patient's cardiac and pulmonary function, systemic condition, and other relevant factors.