Rib fractures occur when ribs bend and break either inward due to direct force or outward due to compressive force applied to the chest. The first to third ribs are short and thick and are protected by the clavicle and scapula, making fractures in this region uncommon. However, significant trauma can cause these ribs to fracture, often accompanied by clavicle or scapular fractures, as well as vascular and nerve injuries in the neck or axilla. The fourth to seventh ribs, being longer and thinner, are more prone to fractures. The eighth to tenth ribs are connected to the sternum by the costal cartilages that form the costal arch, while the eleventh and twelfth ribs are free at the anterior end. Due to their flexibility, these ribs are less likely to fracture. If fractured, there is a higher risk of associated intra-abdominal organ and diaphragmatic injuries. When rib fractures occur without breaching the skin or soft tissues, they are referred to as closed rib fractures. Open rib fractures are those in which the fractured ends communicate with the external environment. Osteoporotic bones in elderly individuals make the ribs more fragile and prone to fractures. Pathological fractures may also occur in ribs with metastatic lesions from malignant tumors.

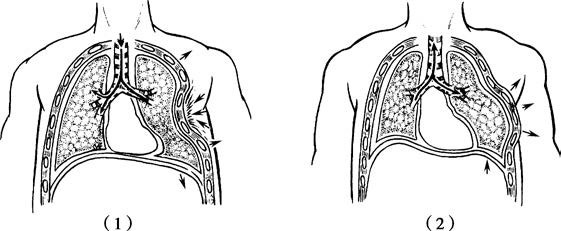

Multiple rib fractures, involving two or more fractures in each of at least two adjacent ribs, result in the chest wall losing its structural support and becoming flail. During spontaneous breathing, paradoxical movement of the chest wall is observed, wherein the flail segment moves inward during inspiration and outward during expiration. This condition, termed flail chest, impairs ventilation, may lead to hypoventilation, and could even trigger respiratory failure.

Figure 1 Flail chest and paradoxical chest wall motion

(1) During inspiration (2) During expiration

Clinical Presentation

Local irritation of intercostal nerves by fractured rib ends often causes pain, which intensifies during deep breathing, coughing, or changes in body position. Chest pain can result in shallow breathing and weak coughing, leading to increased respiratory secretions, retention, atelectasis, and pulmonary infections. Displacement of the fracture ends inward may perforate the pleura, intercostal vessels, or lung tissue, leading to complications such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, or hemoptysis. In the late stages, displaced fracture ends can cause delayed hemothorax or hemopneumothorax. In flail chest, paradoxical breathing movements create imbalances in intrathoracic pressure between the two chest cavities, leading to mediastinal oscillation and impaired ventilation. This condition may result in hypoxia and carbon dioxide retention, potentially progressing to respiratory and circulatory failure in severe cases. Flail chest is often accompanied by extensive pulmonary contusions, where interstitial or alveolar edema in the contused region impairs oxygen diffusion and results in hypoxemia.

Diagnosis

Physical examination may reveal chest wall deformities or significant localized tenderness. Indirect compression exacerbates pain at the fracture site and may produce bone crepitus, aiding differentiation from soft tissue contusion. Chest X-rays in anteroposterior and lateral views can detect fracture lines and misalignment of rib ends, but they have a relatively high rate of missed diagnoses and cannot identify costal cartilage fractures. Chest CT scans provide more accurate detection of rib fractures and can reveal associated injuries such as pulmonary contusions or lacerations, mediastinal hematomas, damage to major thoracic vessels, or cardiac tamponade. CT with three-dimensional reconstruction allows precise assessment of fracture displacement, offering valuable guidance for treatment planning. Ultrasound can help detect concurrent pleural effusion, pneumothorax, hemothorax, pericardial effusion, and abdominal organ injuries, as well as evaluate hemodynamic status.

Treatment

The principles of rib fracture management include effective pain control, appropriate fracture stabilization, pulmonary physiotherapy, and early mobilization. Effective analgesia improves respiratory function, reduces pulmonary complications, minimizes the need for mechanical ventilation, shortens ICU and hospital stays, and facilitates early patient mobilization, subsequently lowering treatment costs. Uncomplicated rib fractures typically require oral or intramuscular analgesics, while multiple rib fractures necessitate sustained and effective pain management. Options include intercostal nerve blocks, pleural analgesia, epidural analgesia, and intravenous analgesia. Intercostal nerve blocks are simple but provide short-term relief. Pleural analgesia has variable efficacy and may suppress phrenic nerve function. Epidural analgesia involves repeated or continuous administration of local anesthetics and analgesics into the epidural space at the level of the affected spinal nerves, offering superior regional pain control. This technique also facilitates patient-controlled analgesia and minimizes sedation, cough suppression, and respiratory depression associated with systemic venous analgesia.

Closed Single Rib Fractures

The adjacent intact ribs and intercostal muscles generally stabilize the fracture ends, reducing the likelihood of displacement, mobility, or overlapping of the fractured segments. Application of a multi-head thoracic belt or elastic chest band can stabilize the chest wall, reduce movement at fracture sites, and alleviate pain.

Closed Multiple Rib Fractures

Effective pain management and respiratory care form the mainstay of treatment. For patients experiencing weak coughing and secretion retention, fiberoptic bronchoscopy-guided suctioning and pulmonary physiotherapy can be employed. Patients with respiratory insufficiency may require endotracheal intubation and positive-pressure ventilation, which also serves as an "internal fixation" for the floating chest wall. For patients with multiple rib fractures in the posterior or lateral chest wall and a limited range of thoracic wall softening, bracing can be used if paradoxical breathing is not severe.

Surgical Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Rib Fractures

Surgical intervention is indicated for flail chest, unstable fractures with significant displacement, displaced lower rib fractures with potential associated organ or vascular injuries, or the presence of conditions such as hemothorax or pneumothorax requiring thoracic exploration. For open rib fractures, thorough debridement of chest wall wounds is necessary. Fracture reduction and fixation can be performed using conventional thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic techniques.