Basilar invagination, also referred to as basilar impression, is a condition in which the bony structures surrounding the foramen magnum invaginate into the cranial cavity. Its primary characteristic is the upward displacement of the odontoid process of the axis beyond its normal level, protruding into the foramen magnum. This results in shortening of the anteroposterior diameter of the foramen magnum and narrowing of the craniocervical junction, compressing the ventral surface of the medulla and cervical spinal cord and causing traction on the adjacent nerves. Basilar invagination often arises from congenital developmental abnormalities and is frequently associated with other malformations, such as platybasia, atlantoaxial dislocation, atlanto-occipital fusion, and Chiari malformation. It may also occur secondary to conditions like osteomalacia, Paget's disease, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Clinical Manifestations

In infancy, cranial base and cervical vertebrae ossification is incomplete, and the tissues are soft and elastic, which usually prevents clinical symptoms at this stage.

In adulthood, the condition may progress as instability develops in the craniocervical junction. Symptoms of medullary and cervical spinal cord compression, as well as damage to adjacent cranial or spinal nerves, may gradually emerge. These symptoms include ataxia, motor and sensory impairments of the limbs and trunk, hoarseness, choking while drinking, difficulty swallowing, and respiratory suppression. In severe cases, complications such as hydrocephalus and syringomyelia may develop, leading to corresponding clinical presentations. Distinctive physical features, such as a short neck, low posterior hairline, head tilt, and asymmetry of the face and ears, may suggest the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

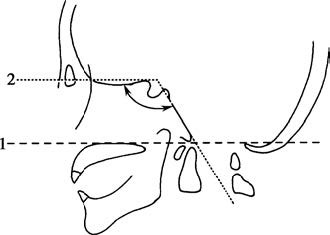

The diagnosis can be supported by characteristic findings on imaging studies. On lateral X-rays of the skull, the Chamberlain line (a line drawn from the posterior edge of the hard palate to the posterior margin of the foramen magnum) can be measured. Normally, the odontoid process lies below this line; if the odontoid process is positioned more than 3 mm above the Chamberlain line, basilar invagination is diagnosed. Additionally, the Boogaard angle (the angle formed by the anterior cranial fossa base and the clivus) can be measured, with normal values ranging from 115° to 145°. Values exceeding 145° are indicative of platybasia. Thin-slice CT scans of the skull base and three-dimensional reconstruction provide detailed visualization of bony abnormalities. MRI clearly shows the areas of compression affecting the medulla and cervical spinal cord, as well as any associated cerebellar tonsillar herniation.

Figure 1 Lateral X-ray of the skull

1, Chamberlain line

2, Boogaard angle

Treatment

The need for surgical intervention in basilar invagination depends on the presence of clinical symptoms and whether atlantoaxial dislocation is observed. Patients without significant clinical symptoms may not require immediate surgery and can be monitored with regular follow-up. In cases involving atlantoaxial dislocation, where craniocervical junction instability is typically associated with earlier and more pronounced symptoms, timely surgical treatment is recommended.

Surgical options include posterior suboccipital decompression and odontoid process reduction (both vertical and anteroposterior reduction) combined with bone graft fusion. In some cases, anterior approaches (through the oral cavity or nasal cavity) for odontoid process detachment and/or resection may be required prior to posterior reduction and stabilization.