Intraspinal tumors refer to primary or metastatic tumors that arise within the spinal cord itself or in adjacent structures within the spinal canal, including spinal nerve roots, dura mater, blood vessels, fatty tissue, or remnants of embryonic tissue.

Classification and Pathology

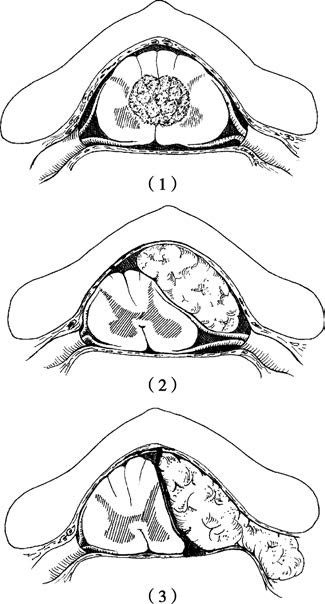

Based on the tumor's location relative to the spinal cord and dura mater, intraspinal tumors are typically categorized into three types: intramedullary, extramedullary intradural, and extradural. Some tumors may exhibit a dumbbell-shaped growth, affecting more than one of these regions simultaneously.

Figure 1 Locations of intraspinal tumors:

(1) Intramedullary tumors

(2) Extramedullary intradural tumors

(3) Extradural tumors

Intramedullary tumors account for approximately 20% of intraspinal tumors, with common types including ependymomas and astrocytomas, in addition to vascular tumors and tumors originating from embryonic remnants. Extramedullary intradural tumors are the most common, making up about 55% of cases, and are predominantly benign. Common examples include schwannomas, meningiomas, and neurofibromas. Extradural tumors account for about 25% of cases and are often malignant, arising from the vertebral body or extradural tissues, such as metastatic carcinomas or sarcomas. Other examples include osteomas, chondromas, chordomas, and lipomas.

Clinical Features

Due to the narrow space within the spinal canal and the presence of critical structures such as the spinal cord and nerve roots, even small lesions can cause significant functional impairments. Tumors affect the spinal cord and nerve roots primarily through compression or infiltrative destruction. Compression is more common in benign tumors with a firmer consistency, which can severely impact spinal blood circulation, leading to localized ischemia, edema, and degenerative necrosis. Infiltrative damage is often associated with malignant, softer tumors that erode spinal tissue and cause transverse spinal cord damage in a short period. Symptoms vary depending on the spinal segment involved, the tumor's intramedullary or extramedullary location, and its nature.

Radicular Pain

Radicular pain is the most common early symptom of spinal cord tumors. It arises from irritation of the posterior spinal nerve root, cells of the dorsal horn, sensory conduction tracts, or compression/tension of the dura mater, often exacerbated by positional changes that stretch the spinal cord. The pain's location corresponds to the neural distribution at the tumor's level, which aids in localization during diagnosis. Radicular pain is frequently the initial symptom of extramedullary space-occupying lesions and is more common in cervical and cauda equina tumors. Extradural metastatic tumors often cause the most severe pain.

Sensory Disturbances

Compression of sensory fibers initially results in sensory reduction and paresthesia, progressing to sensory loss when fibers are destroyed. Extramedullary tumors pressing on one side of the spinal cord can cause spinal cord displacement and lead to Brown-Séquard syndrome, characterized by ipsilateral paralysis and loss of deep sensation below the tumor level, with contralateral impairment or loss of pain and temperature sensations. Intramedullary tumors growing along the midline of the spinal cord tend to symmetrically compress spinal cord tissue without Brown-Séquard syndrome.

Motor Dysfunction and Reflex Abnormalities

Motor dysfunction arises from tumor compression of the anterior nerve roots or anterior horn of the spinal cord, leading to lower motor neuron paralysis in the corresponding muscle groups. Symptoms include muscle hypotonia, diminished or absent tendon reflexes, muscle atrophy, and negative pathological reflexes. Compression of the spinal cord pyramidal tract below the tumor level results in upper motor neuron paralysis, characterized by increased muscle tone, hyperactive tendon reflexes, lack of muscle atrophy, and positive pathological reflexes. Tumors in the conus medullaris or cauda equina regions primarily compress nerve roots, causing lower motor neuron paralysis.

Autonomic Dysfunction

Autonomic disturbances most commonly involve bladder and rectal dysfunction. Impaired autonomic pathways can result in diminished or absent sweating below the tumor level, and lesions above the T2 level may disrupt the ciliospinal center, leading to ipsilateral Horner syndrome. Tumors compressing spinal segments above the lumbosacral region can leave the bladder reflex center intact, resulting in reflexive urination when the bladder fills. Tumors affecting the lumbosacral reflex center can cause central damage, leading to urinary retention, followed by overflow incontinence when the bladder becomes overly full. Compression above sacral segments can result in constipation, while lesions below sacral segments may cause anal sphincter relaxation and fecal incontinence.

Diagnosis

A thorough medical history, physical examination, and neurological assessment help localize the spinal segment affected by the tumor. MRI scans provide detailed visualization of tumors, cerebrospinal fluid, and neural tissue, though their depiction of osseous structures is inferior to CT or plain X-rays. CT scans may show spinal canal widening, vertebral body compression or destruction, and soft tissue occupation within the canal. Spinal angiography can be useful for excluding arteriovenous malformations (AVM).

Treatment

Once a definitive diagnosis of intraspinal tumor is established, surgical intervention is recommended at the earliest opportunity. Complete resection of infiltrative intramedullary tumors may be challenging, and surgical principles focus on maximizing tumor removal while protecting neurological function. Adequate spinal decompression is achieved to relieve spinal cord compression. For patients with spinal instability, spinal fusion and internal fixation may be performed in the same surgical session.