Vestibular Schwannoma originates from the Schwann cells of the vestibular nerve, occurring in the segment of the internal auditory canal. Clinically, it is commonly referred to as acoustic neuroma and is a benign tumor. It accounts for 8%–10% of intracranial tumors, with an annual incidence of approximately 1.5 per 100,000. For patients under the age of 40, the possibility of neurofibromatosis should be considered. The tumor typically presents insidiously with unilateral high-frequency tinnitus, followed by a gradual loss of hearing. Most cases in the early stage exhibit a classic triad of ipsilateral sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and balance disturbances. Large vestibular schwannomas may compress the brainstem and cerebellum, obstruct cerebrospinal fluid circulation, and lead to elevated intracranial pressure.

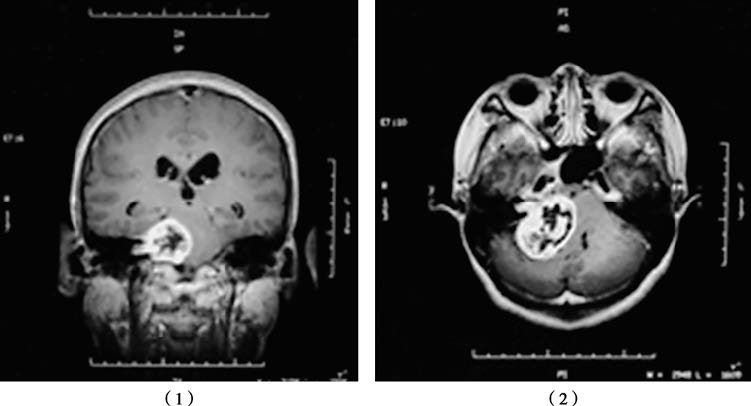

Thin-slice axial MRI scans often identify a round or oval-shaped contrast-enhancing mass in the internal auditory canal, with larger tumors potentially showing cystic degeneration. CT scans may reveal an expanded internal auditory canal with a funnel-shaped appearance and associated bone erosion.

Figure 1 MRI scans of a right-sided vestibular schwannoma in coronal (1) and axial (2) views, showing a round lesion in the internal auditory canal.

Treatment plans are tailored based on the patient’s age, tumor size, preoperative hearing status, and the extent of cranial nerve impairment. For elderly patients or those with tumors measuring less than 1.5 cm in diameter, close monitoring of hearing changes with regular imaging and audiometric evaluations may be considered. If rapid tumor growth is observed, surgical intervention becomes necessary. For tumors larger than 2.5 cm in diameter, complete resection is generally recommended. In cases involving elderly patients, poor overall health, tumor diameters smaller than 3.0 cm, or residual tumor after surgery, stereotactic radiotherapy may be considered as an alternative treatment option.