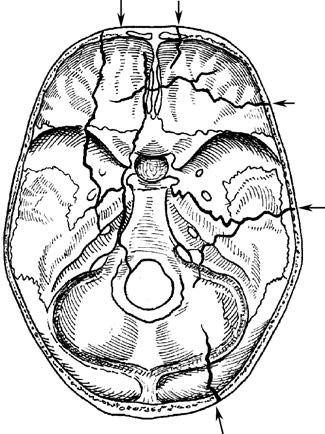

A skull base fracture can result from an extension of a skull vault fracture or, less commonly, from head crush injuries or impacts localized at the skull base level. Most skull base fractures are linear, though comminuted fractures may also occur. Due to the anatomical features of the skull base, transverse fracture lines in the anterior cranial fossa may extend from the orbital roof to the cribriform plate, while in the middle cranial fossa, they often follow the anterior edge of the petrous part of the temporal bone or even traverse the sella turcica. Longitudinal fracture lines near the midline frequently involve the cribriform plate, optic canal, foramen lacerum, medial petrous temporal bone, and petro-occipital fissure, extending to the foramen magnum. Lateral fracture lines may affect the orbital roof, foramen rotundum, and foramen ovale, sometimes causing transverse fractures of the petrous temporal bone.

Figure 1 Common locations of skull base fracture lines

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Anterior Cranial Fossa Fracture

Fractures often involve the horizontal part of the frontal bone (orbital roof) and ethmoid bone. Hemorrhage from the fracture may drain through the anterior nostrils or into the orbit, forming subcutaneous ecchymoses in the eyelids and conjunctiva, known as the "raccoon eyes" or "panda eyes" sign. If the meninges are torn, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may leak through the nasal cavity (CSF rhinorrhea). Intracranial air (pneumocephalus) may enter via the fracture, and olfactory nerve injury is common.

Middle Cranial Fossa Fracture

Fractures may involve the sphenoid and temporal bones. Blood and CSF can flow into the nasopharynx via the sphenoid sinus. If the petrous temporal bone is fractured, blood and CSF may drain through the middle ear and ruptured tympanic membrane (CSF otorrhea) or, if the tympanic membrane is intact, into the nasopharynx via the Eustachian tube. Facial and auditory nerve injuries are common. Midline fractures may damage the optic, oculomotor, trochlear, trigeminal, and abducens nerves.

Posterior Cranial Fossa Fracture

Fractures typically involve the petrous temporal bone and occipital base. Subcutaneous ecchymoses may appear over the mastoid process (Battle’s sign) or in the retropharyngeal mucosa. Midline fractures may injure the glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory, and hypoglossal nerves. Carotid artery injury may lead to carotid-cavernous fistula or epistaxis.

Diagnosis relies on clinical findings, confirmed by cranial CT. High-resolution CT (HRCT) of the skull base helps localize fractures, while thin-slice MRI T2-weighted imaging aids in identifying CSF leakage sites.

Treatment

Closed skull base fractures typically do not require special intervention. If cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage is present, the patient should remain in a high-head-positioned, strict bed rest posture and avoid actions such as forceful coughing, sneezing, or nose-blowing. Antibiotics are often administered to prevent intracranial infection. In most cases, the fracture site is not sealed or irrigated, and lumbar puncture is not performed. The majority of CSF leaks tend to resolve spontaneously within 1 to 2 weeks after injury. If leakage persists for more than one month, surgical repair of the leak may be considered. If vision deteriorates after the injury and is suspected to be caused by bone fragment compression or hematoma pressing on the optic nerve, optic nerve decompression should ideally be performed within 24 hours.