Orbital meningioma can originate primarily within the orbit or secondarily from intracranial sources. Primary orbital meningiomas arise from the arachnoid of the optic nerve sheath or ectopic meningeal cells within the orbit. Secondary orbital meningiomas commonly result from sphenoid ridge meningiomas extending into the orbit through the optic canal or superior orbital fissure. Meningiomas originating from the arachnoid of the optic nerve sheath are referred to as optic nerve sheath meningiomas. These are relatively common and are predominantly observed in middle-aged women.

Clinical Manifestations

The primary clinical manifestations include chronic proptosis and progressive vision loss. The classic presentation of optic nerve sheath meningioma consists of four features—visual decline, proptosis, chronic optic disc edema or atrophy, and dilated opticociliary veins—collectively referred to as the quadripartite syndrome of optic nerve sheath meningioma. The tumor may extend along the optic nerve or through the superior orbital fissure, connecting the orbit and the cranial cavity.

Meningiomas originating from the sphenoid ridge can extend into the orbit through the optic canal or superior orbital fissure. Compression of the optic nerve may result in ipsilateral primary optic atrophy. With tumor growth, increased intracranial pressure can cause contralateral optic disc edema, presenting as ipsilateral nerve atrophy accompanied by contralateral disc swelling. This condition is known as Foster-Kennedy syndrome.

Sphenoid ridge meningiomas that spread into the orbit often lead to bony hyperplasia of the orbital walls. A soft tissue mass in the orbital apex with accompanying bone overgrowth should raise a strong suspicion for this condition.

On CT imaging, optic nerve sheath meningiomas are characterized by tubular thickening of the optic nerve and enlargement of the optic canal, with potential calcification. Sphenoid ridge meningiomas that extend into the orbit typically show features of both soft tissue masses and bony hyperplasia, with indistinct mass margins, thickened orbital walls, and in some cases, a hemispherical protrusion of the orbital bone.

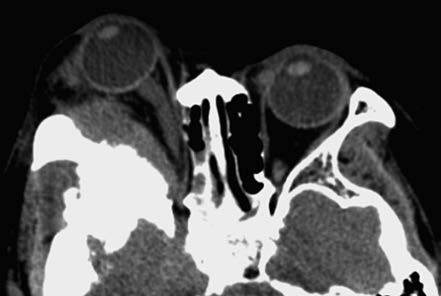

Figure 1 CT image of left optic nerve sheath meningioma

Axial CT reveals tubular thickening of the left optic nerve and enlargement of the optic canal.

Figure 2 CT image of right orbital meningioma

Axial CT shows thickening of the right orbital wall with hemispherical protrusion.

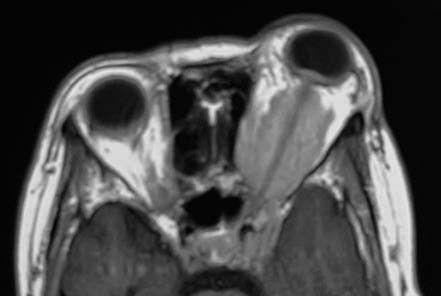

Figure 3 MRI of left optic nerve sheath meningioma

Axial T1-weighted MRI displays a tumor surrounding the left optic nerve, appearing as a hypointense signal with the characteristic "railroad sign."

MRI imaging shows the tumor as isointense to hypointense on T1-weighted images (T1WI) and hyperintense to moderately hyperintense on T2-weighted images (T2WI). Post-contrast enhancement reveals significant enhancement, with characteristic features such as the "railroad sign," where high signal intensity is observed along the optic nerve sheath, while the optic nerve fibers themselves appear at lower density, mimicking the appearance of train tracks. MRI is superior to CT in identifying cranio-orbital junctional lesions.

Treatment

For small optic nerve meningiomas confined to the orbit, close monitoring with imaging may be an option. Gamma Knife therapy can be utilized to temporarily preserve vision for a certain period. In cases of progressive tumor growth or signs of intracranial extension, surgical removal may be performed if non-surgical treatments prove ineffective. However, surgery inevitably results in complete loss of vision post-procedure.

Complete removal of meningiomas originating from the sphenoid ridge is often challenging, and recurrence following surgery is common. In such cases, orbital exenteration may be considered when necessary. However, the procedure severely affects facial aesthetics postoperatively.