Idiopathic orbital inflammation (IOI), formerly known as orbital inflammatory pseudotumor, is classified as nonspecific orbital inflammation. It is a relatively common condition, predominantly observed in adults, and shows no significant gender or racial differences. The etiology and pathogenesis remain unclear, though it is currently considered a noninfectious, nongranulomatous idiopathic inflammatory response caused by local immune dysregulation in the orbit. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the type of lesion, the affected area, and the course of the disease.

Etiology

The precise cause of idiopathic orbital inflammation is unknown. It is generally believed to be a nonspecific immune-mediated disorder.

Clinical Manifestations

Based on histopathological classifications, idiopathic orbital inflammation can be divided into classic, granulomatous, vasculitic, eosinophilic, and sclerosing subtypes, each with distinct features. By the anatomical site of involvement, it is further categorized into localized and diffuse disease. Localized disease may manifest as myositis, dacryoadenitis, perineuritis of the optic nerve, orbital inflammatory masses, or scleritis. Clinical presentations differ depending on the area involved. Despite its variability, the common feature across all forms is the dual effect of inflammation and space-occupying lesions.

Myositis

This subtype involves one or multiple extraocular muscles, with the lateral rectus muscle being most commonly affected. A hallmark feature is significant hyperemia and thickening of the muscle belly and its tendon, including the insertion point, which may appear as dark red, swollen muscles visible through the conjunctiva. Symptoms often include varying degrees of proptosis, restricted eye movement, diplopia, orbital pain, and, in some cases, ptosis. In advanced stages, muscle fibrosis may fixate the globe in certain positions. CT scans display band-like thickening of extraocular muscles, with simultaneous involvement of the muscle belly and attachment sites, distinguishing IOI from thyroid eye disease.

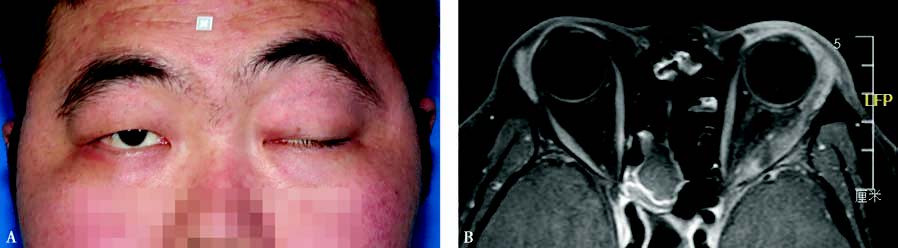

Figure 1 Myositis of the left orbit

A. Left exotropia, eyelid swelling, and ptosis observed.

B. MRI shows significant thickening of the lateral rectus muscle in the left eye, with involvement of both the muscle belly and the attachment site.

Dacryoadenitis

This form primarily affects the lacrimal glands, either unilaterally or bilaterally. Patients may report excessive tearing or a sensation of dryness. Clinical findings typically include congestion and edema of the upper eyelid, most prominent laterally, giving the upper eyelid margin an "S-shaped" appearance. Congestion is often seen in the conjunctiva of the lacrimal gland area, where a round, moderately firm, poorly mobile, and tender mass may be palpable. CT imaging reveals diffuse enlargement of the lacrimal gland, with normal bone structure in the region of the lacrimal fossa. In cases of pronounced enlargement, the lacrimal gland may extend posteriorly into a flattened shape.

Periscleritis and Perineuritis of the Optic Nerve

This subtype involves inflammation of the fascial planes surrounding the sclera and optic nerve sheath within the anterior one-third. Symptoms primarily include pain and decreased vision. Fundus examination reveals optic disc hyperemia and retinal vein dilation. CT imaging displays thickened optic nerves, while B-scan ultrasonography shows posterior scleral thickening and fascial edema, giving rise to the characteristic "T-sign."

Diffuse Inflammation

This form involves widespread infiltration of the soft tissue structures in the orbit. Common symptoms include proptosis, periocular swelling, increased orbital pressure, lacrimal gland enlargement, extraocular muscle thickening, and even optic nerve thickening. CT scans demonstrate diffuse soft-tissue changes in the orbit, including involvement of the lacrimal gland, extraocular muscles, and indistinct lesion margins with generally homogeneous density.

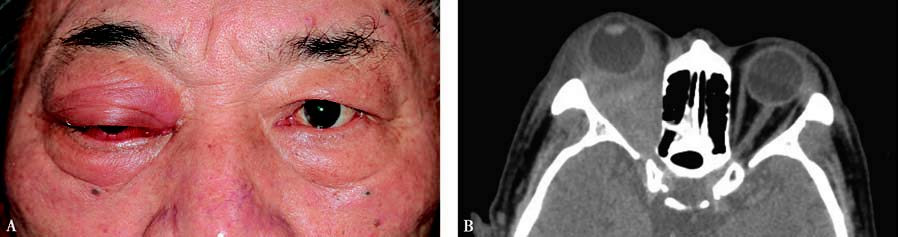

Figure 2 Idiopathic inflammation of the right orbit

A. Proptosis of the right eye, with eyelid and conjunctival edema.

B. CT scan shows diffuse soft-tissue lesions in the orbit, with unclear boundaries.

Orbital Inflammatory Mass

This chronic manifestation is relatively common, with either single or multiple masses in the orbit. A mass located in the anterior orbit may cause globe displacement, while one in the deep orbit may lead to proptosis and restricted eye movement. CT imaging shows localized orbital soft-tissue masses with poorly defined borders and homogeneously increased density. Secondary changes may arise due to mass effect.

Idiopathic orbital inflammation involving different orbital regions may produce corresponding clinical symptoms. Additionally, symptomatology is closely related to the histological subtype of the lesion. The classic subtype, also known as lymphocytic infiltration, is characterized by infiltration of plasma cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and eosinophils, accompanied by varying degrees of fibrosis and edema. In the early stages, prominent inflammatory symptoms may resolve with treatment or spontaneous recovery, and some patients may retain normal ocular function, even after multiple disease recurrences. However, the sclerosing subtype has a less pronounced inflammatory onset. Proptosis and soft tissue swelling are minimal, but progressive fibrosis of orbital tissues leads to rapid disease progression. Increased orbital pressure, tissue induration, significant ocular motility limitation, diplopia, and considerable impairment of ocular functions are characteristic. The sclerosing subtype is often less responsive to treatment, and prognosis tends to be poor.

Diagnosis

In addition to clinical manifestations, the typical features of intraorbital space-occupying lesions observed on CT imaging can help distinguish idiopathic orbital inflammation from thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Ultrasound examinations often reveal hypoechoic lesions, with some appearing anechoic; lesions with fibrotic proliferation typically show significant acoustic attenuation. For cases with uncertain diagnosis or poor treatment response, differentiation from lymphoma should be considered. Biopsy may be required in such cases.

Treatment

Therapeutic efficacy is closely related to the histological type of the lesion. The lymphocytic infiltration subtype is typically sensitive to corticosteroids. Depending on the severity of the condition, they can be administered intravenously or orally, with the general principle being high-dose pulsed therapy followed by low-dose maintenance therapy once the disease is controlled. Perilesional orbital injections of triamcinolone acetonide (40 mg; with caution in children) are often effective, with treatments performed once per month for a total of three to four sessions. For cases unresponsive to medication, those with contraindications, or those with frequent recurrences, orbital radiation therapy with a total dose of approximately 20 Gy may be employed. Additional immunosuppressive agents, including biologics such as rituximab and infliximab, have been used in refractory cases.

The sclerosing subtype of idiopathic orbital inflammation often exhibits poor sensitivity to both medication and radiation therapy. Orbital physical therapy can be utilized to soften scarring and slow the progression of fibrosis. Surgical removal of orbital masses may be considered for all subtypes when appropriate, with the aim of relieving proptosis or repositioning extraocular muscles to correct diplopia. However, surgery can be challenging in cases with extensive fibrosis. Residual disease and recurrence post-surgery remain common clinical problems across all types of idiopathic orbital inflammation.