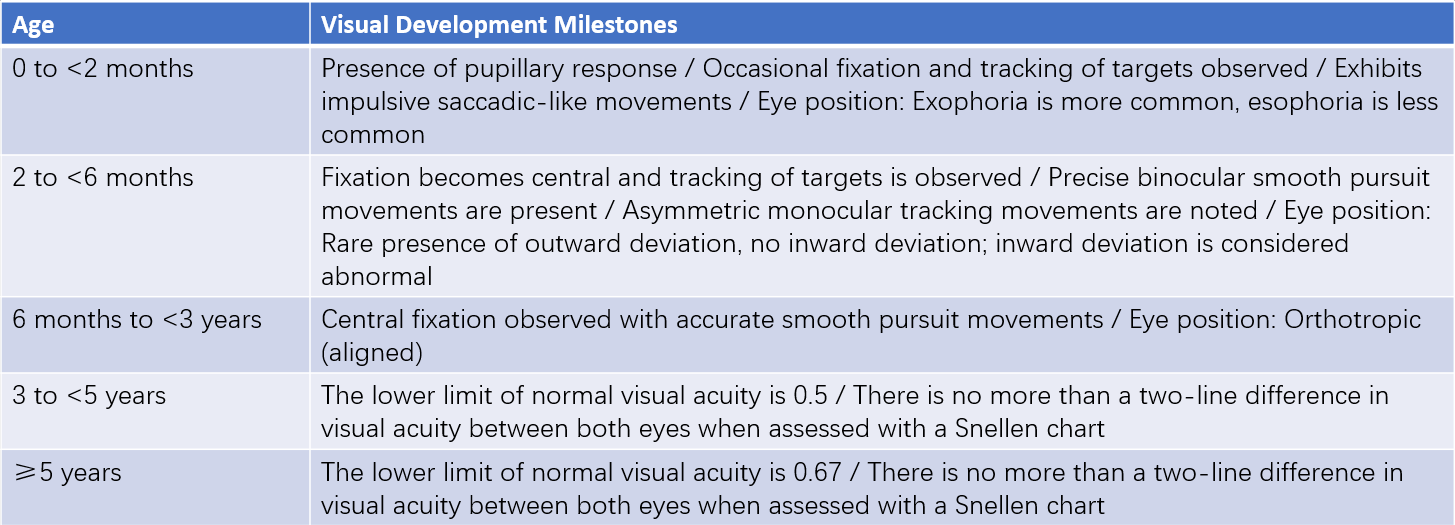

Amblyopia is a developmental visual disorder, making an understanding of visual development crucial for its diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Visual acuity in children develops progressively. The critical period for visual development is from birth to 3 years of age, with a sensitive period extending to 12 years. Binocular vision development is typically complete by the age of 6–8 years. Milestones in visual development at different stages highlight the need to consider age as a factor when diagnosing amblyopia.

Table 1 Milestones in visual development at different stages

Classification and Etiology

Strabismic Amblyopia

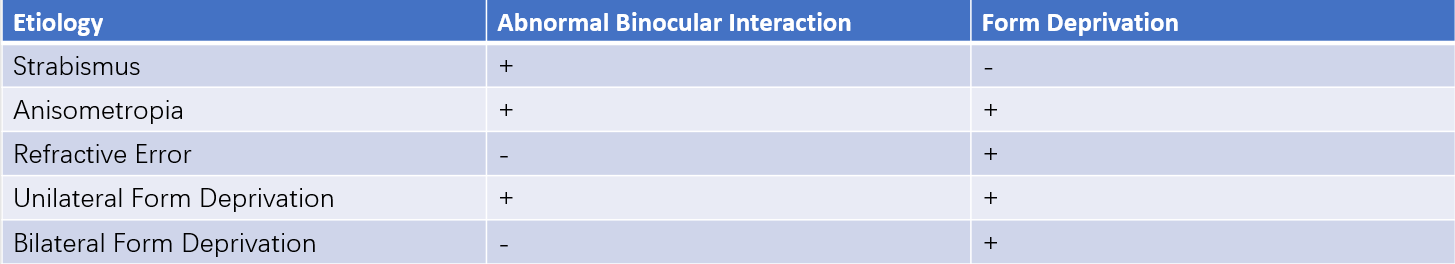

This primarily occurs in cases of monocular strabismus, with esotropia being most commonly observed. The misalignment of the eyes leads to abnormal binocular interaction, where the image formed on the fovea of the strabismic eye is suppressed, causing reduced best-corrected visual acuity in the affected eye.

Anisometropic Amblyopia

This occurs due to significant differences in refractive error between the two eyes, resulting in images of unequal size or clarity on the macula. The eye with the higher refractive error undergoes form deprivation, leading to amblyopia. A spherical dioptric difference of ≥1.50DS or a cylindrical dioptric difference of ≥1.00DC between the two eyes can lead to the development of anisometropic amblyopia in the eye with the higher refractive error.

Refractive Amblyopia

This occurs mostly in individuals with uncorrected high refractive errors and is commonly associated with high hyperopia or astigmatism. It is often bilateral, with the best-corrected visual acuity in both eyes being equal or nearly equal. Individuals with hyperopia ≥4.00DS, astigmatism ≥2.00DC, or myopia ≥5.00DS are considered at increased risk for this type of amblyopia.

Deprivation Amblyopia

This type is commonly seen in children with optical media opacities, such as congenital cataracts or corneal opacities, as well as in cases of complete ptosis, iatrogenic eyelid suturing, or occlusion. Reduced visual stimulation deprives the macula of the ability to form clear images, resulting in amblyopia. Deprivation amblyopia may be unilateral or bilateral, with unilateral cases generally being more severe. The time required for deprivation amblyopia to develop is shorter than that for strabismic, refractive, or anisometropic amblyopia. Even brief periods of monocular occlusion during infancy can result in deprivation amblyopia, emphasizing the importance of avoiding inappropriate occlusion during the critical period of visual development.

Pathogenesis

The mechanisms underlying amblyopia are complex. Two widely accepted theories explain its development: abnormal binocular interaction and form deprivation.

Table 2 Mechanisms of amblyopia by etiology

Diagnosis

A comprehensive ocular evaluation is essential before making a diagnosis and should include assessments of visual acuity, fixation patterns, refractive status, ocular alignment, eye movements, binocular function, and both anterior and posterior segment examinations. Additional tests, such as electrophysiology, color vision testing, and visual field analysis, may be necessary. Diagnosis requires both subnormal best-corrected visual acuity for the child's developmental age and the presence of a corresponding risk factor (e.g., monocular strabismus, anisometropia, high refractive error, or form deprivation); both criteria must be fulfilled.

Diagnostic thresholds for normal visual acuity in children vary by age. For children aged 3–5 years, the lower limit of normal visual acuity is 0.5, while for those aged 5 years and older, it is 0.67. Amblyopia is considered present if there is a difference of 2 or more lines in best-corrected visual acuity between the two eyes, with the worse eye identified as amblyopic. For young children, qualitatively assessing whether monocular vision loss is present is often more important than quantitative measurements.

Overdiagnosis of amblyopia can occur when some healthcare providers diagnose amblyopia and initiate treatment for any child with a best-corrected visual acuity below 0.8 without considering the child’s age. In cases where the best-corrected visual acuity is subnormal for the age but no identifiable risk factors for amblyopia are present, further investigation is necessary to rule out organic causes, such as subtle retinal or optic nerve abnormalities. Amblyopia should not be diagnosed in children whose best-corrected visual acuity meets the age-specific threshold, whose inter-eye difference is less than 2 lines, and who lack identifiable risk factors; these cases should be observed rather than immediately diagnosed as amblyopia.

Screening and Prevention

Population-based randomized controlled studies have demonstrated that early screening improves detection of risk factors for amblyopia (e.g., strabismus and refractive errors). Earlier identification and intervention are associated with a greater likelihood of preventing amblyopia and achieving successful treatment outcomes.

Treatment

Once amblyopia is diagnosed, treatment should begin immediately. The effectiveness of amblyopia treatment is closely related to the timing of intervention; earlier onset and later treatment generally result in poorer outcomes. The fundamental strategies for amblyopia treatment involve addressing the underlying cause of form deprivation, correcting clinically significant refractive errors, and encouraging the use of the amblyopic eye.

Elimination of the Underlying Cause

Early interventions, such as the treatment of congenital cataracts or complete congenital ptosis, help to eliminate the cause of form deprivation.

Refractive Correction

Accurate prescription of corrective lenses for clinically significant refractive errors can improve visual acuity in children with anisometropic amblyopia or strabismic amblyopia. Children with high refractive amblyopia often achieve substantial vision improvement solely through refractive correction. For cases of monocular amblyopia, improvements are more effective when refractive correction and elimination of the underlying cause are combined with interventions to promote the use of the amblyopic eye.

Occlusion Therapy

Occlusion therapy involves covering the dominant eye to force the amblyopic eye to be used. This method, which has been in use for over 200 years, remains the most effective treatment for monocular amblyopia. Compliance is a key determinant of treatment success. Multicenter randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that, for moderate amblyopia, occlusion for 2 hours per day provides equivalent outcomes to 6 hours per day, and for severe amblyopia, 6 hours of occlusion is as effective as full-day occlusion. Increased occlusion duration may be considered if the response to treatment is inadequate. Occlusion therapy is the preferred treatment for deprivation amblyopia.

Occlusion therapy remains applicable for older children and adolescents, particularly those who have not received prior treatment. Close monitoring of the visual acuity of the occluded eye is necessary during therapy to prevent the development of occlusion amblyopia.

Optical and Pharmacological Therapies (Penalization Therapy)

Studies have shown that patients with mild to moderate anisometropia, where one eye is used for distance vision and the other for near vision, do not develop amblyopia. Based on this observation, penalization therapies are designed to artificially create a situation where one eye is favored for distance and the other for near vision. This approach forms the basis of amblyopia treatment using penalization.

Penalization therapy is suitable for mild to moderate monocular amblyopia, cases with latent nystagmus, children with poor compliance to occlusion therapy, or for maintenance therapy. Optical penalization therapy is generally not recommended. Pharmacological penalization often involves the use of 1% atropine eye drops or gel. Multicenter randomized controlled trials have reported that, for moderate amblyopia, weekend-only atropine therapy produces outcomes comparable to daily atropine use. For mild to moderate amblyopia in children aged 3–15 years, similar efficacy has been shown between occlusion therapy and atropine penalization therapy, and both serve as appropriate initial treatments for this population.

Other Therapies

Afterimage therapy, red filter techniques, and Haidinger brush stimulation are effective methods for treating amblyopia, especially in patients with eccentric fixation. Vision-stimulation therapies are particularly effective for central fixation and refractive amblyopia and can serve as adjuncts to occlusion therapy to reduce the duration of treatment. The latest clinical guidelines for amblyopia now include dichoptic training as a potential treatment, though its efficacy requires further confirmation.

Comprehensive Therapies

For cases of central fixation amblyopia, standard occlusion or penalization therapies can be combined with vision-stimulation techniques and fine motor training as adjunctive therapies. For cases of eccentric fixation amblyopia, methods such as afterimage stimulation, red filter techniques, or Haidinger brush exercises can be used to shift fixation to central. Once central fixation is achieved, amblyopia treatment can proceed using protocols for central fixation amblyopia, though direct occlusion therapy may also be applied.

Follow-Up

Amblyopia treatment is a long-term process requiring periodic follow-up to adjust treatment plans and dosages as needed. Follow-up intervals are primarily determined by the child's age, with intervals typically ranging from 2 to 3 months; younger children require shorter intervals. Follow-up assessments include monitoring the visual acuity of the amblyopic eye, treatment compliance, side effects, and the visual acuity of the fellow eye. Since amblyopia treatment is prone to relapse, a gradual reduction in treatment intensity is necessary after achieving balanced visual acuity in both eyes. Maintenance therapy should continue for at least six months to ensure the stability of treatment outcomes.