Exotropia is less common than esotropia during infancy and early childhood but becomes increasingly prevalent with age. It may develop progressively from exophoria to intermittent exotropia and then to constant exotropia. In other cases, it may present initially as intermittent or constant exotropia. Intermittent exotropia is the most common type of strabismus among Asian children. In the early stages, observation may be considered. If binocular vision is at risk or the condition affects the child’s psychological well-being and social interactions, early surgical intervention is recommended. The goals of surgery and muscle selection for exotropia are similar to those for esotropia. As exotropia has a high risk of postoperative recurrence, postoperative orthoptic therapy, such as binocular vision training guided by an orthoptist, may help consolidate surgical outcomes.

Intermittent Exotropia

Classification

Based on the difference in deviation angles between distant and near fixation, intermittent exotropia is clinically classified into four types:

- Basic Type: The deviation angle is approximately the same for both distant and near fixation.

- Divergence Excess Type: The deviation angle is significantly larger for distance fixation than for near fixation (≥15Δ).

- Convergence Insufficiency Type: The deviation angle is significantly larger for near fixation than for distance fixation (≥15Δ).

- Pseudo-Divergence Excess Type: Although the deviation angle is larger for distance fixation than for near fixation, it equalizes between the two conditions after monocular occlusion for one hour or wearing +3.00D lenses binocularly.

Diagnosis

Intermittent exotropia typically has an early onset but may not become evident until around the age of five. Older children and adults without visual suppression may report diplopia. Symptoms such as asthenopia, difficulty reading, blurry vision, and headaches may occur when accommodative convergence is used to control eye alignment. Many patients with intermittent exotropia exhibit photophobia and prefer to close one eye in bright light. The frequency of misalignment tends to increase with age. The deviation, controlled by fusion, is often variable but becomes more apparent during illness, fatigue, or fusion disruption. Binocular visual function is often preserved when alignment is controlled, while suppression occurs when the eye deviates. Normal retinal correspondence is usually maintained, and amblyopia is rare. There is no significant refractive error, and there is no specific association between refractive error and the cause of misalignment.

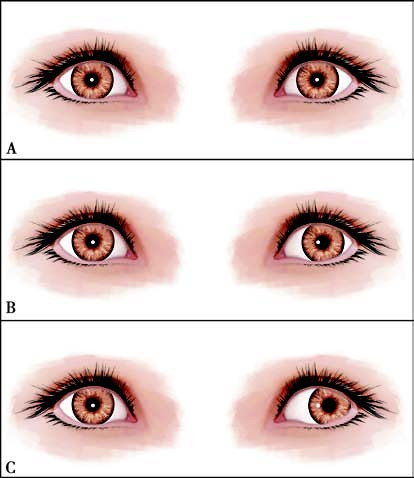

Figure 1 Intermittent exotropia

A. Orthophoria under fusion control; B, C. Varying degrees of deviation under different levels of control.

Treatment

Surgical treatment is the primary approach, with the timing of surgery determined before binocular vision is impaired. For cases where stereopsis remains intact, surgery can be delayed under close monitoring. Early surgery is recommended if binocular vision is compromised, but the child’s cooperation and the reliability of the measured deviation angle must be considered. Surgery should not proceed if examination results are unreliable. Convergence training may provide temporary relief but cannot correct the deviation. Surgery should not be delayed due to convergence training, as this increases the risk of overcorrection postoperatively. Preoperative diagnostic occlusion or prism adaptation is often required to reveal the maximum deviation angle. For cases with a significant deviation in distance fixation, bilateral lateral rectus recession is typically performed. When the deviation for distance and near fixation is similar, long-term outcomes show no significant difference between bilateral lateral rectus recession and unilateral lateral rectus recession combined with medial rectus resection.

Constant Exotropia

Congenital Exotropia

Diagnosis

Congenital exotropia is defined as exotropia with onset before six months of age. It is characterized by a large-angle exotropia and is often associated with neurological abnormalities and craniofacial malformations. Patients typically have poor stereopsis and binocular fixation. Monocular deviation is often accompanied by amblyopia.

Treatment

Surgery is the main treatment approach. If amblyopia is present, amblyopia should be treated first. Surgical alignment should be performed promptly once binocular vision is near balanced. Preoperative evaluation of the central nervous system may be necessary.

Sensory Exotropia

Diagnosis

Sensory exotropia occurs due to primary sensory deficits, such as anisometropia, cataracts, aphakia, retinal disorders, or other organic causes leading to monocular visual impairment. The affected eye exhibits a constant exotropia.

Treatment

Surgery is the main treatment for sensory exotropia. Primary sensory deficits should be addressed first. If they cannot be resolved or treatment is ineffective, surgical alignment is performed.

Consecutive Exotropia

Diagnosis

Consecutive exotropia refers to exotropia that develops following surgical correction of esotropia.

Treatment

Patients with esotropia often have poor binocular vision. When consecutive exotropia occurs, conservative treatments are generally ineffective, and surgical intervention becomes necessary. Most secondary surgeries involve exploration and repositioning of the muscle recessed during the previous procedure.

Oculomotor Nerve Palsy

Diagnosis

In children, oculomotor nerve palsy is primarily caused by congenital factors (40%–50%), trauma, or inflammation, and is rarely due to tumors. In adults, oculomotor nerve palsy is more commonly associated with intracranial aneurysms, diabetes, neuritis, trauma, or infections. Patients typically present with large-angle exotropia accompanied by hypotropia of the affected eye. The affected eye often exhibits ptosis, marked restriction of adduction, and varying degrees of limitation in upward nasal motion, upward temporal motion, and downward temporal motion. When the intraocular muscles are involved, the pupil may become dilated, and the pupillary light reflex may be absent or sluggish.

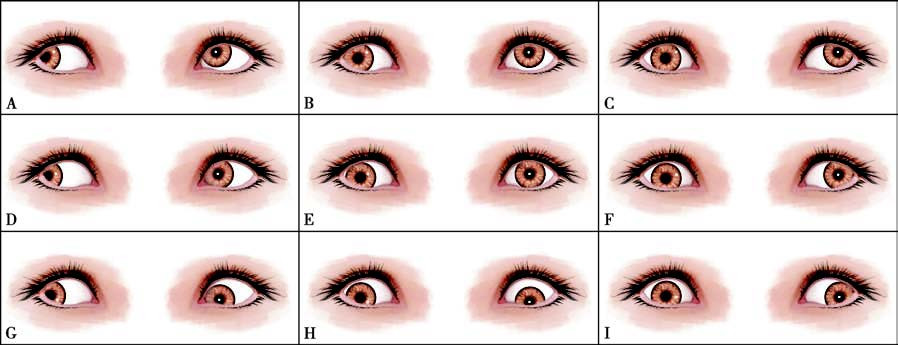

Figure 2 Right oculomotor nerve palsy

A–C. Varying degrees of limitation in upward temporal, upward, and upward nasal movements of the right eye;

D. Normal abduction of the right eye;

E. Hypotropia with the right eye in the primary position;

F. Marked limitation of adduction in the right eye;

G, H. Varying degrees of limitation in downward temporal and downward movements of the right eye;

I. Minimal limitation in downward nasal movement of the right eye.

Amblyopia is common in children with oculomotor nerve palsy, necessitating active treatment. In cases of congenital or traumatic oculomotor nerve palsy, aberrant regeneration of the damaged nerve can complicate both clinical presentation and management. Such cases may show abnormal eyelid elevation, pupil constriction, or downward deviation of the eye when attempting adduction.

Treatment

For acquired oculomotor nerve palsy, identifying the underlying lesion is critical to determine the cause. Diagnoses of significant conditions, such as aneurysms, must not be overlooked, and immediate consultation with a neurologist is recommended when aneurysm is suspected. Neurotrophic medications may be used in cases of nerve palsy as spontaneous recovery is possible. Observation for six months is often recommended, and surgery may be considered if misalignment persists.

Surgical goals focus on achieving orthophoria in the primary gaze rather than restoring normal ocular motility, due to involvement of multiple extraocular muscles, including the levator palpebrae superioris. Surgical correction of large-angle exotropia often requires combined procedures, such as substantial lateral rectus recession along with large medial rectus resection. Surgical outcomes are generally limited due to the extensive involvement of extraocular muscles. In cases where Bell's phenomenon is absent and upward movement is severely restricted, surgery for ptosis correction is approached with caution.