Etiology

Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) results from ischemia affecting small branches of the posterior ciliary arteries that supply the prelaminar and laminar regions of the optic disc, leading to localized infarction of the optic disc. Major causes include:

- Local vascular abnormalities of the optic disc, such as ocular arteritis, arteriosclerosis, or embolic obstruction.

- Increased blood viscosity, as seen in conditions like polycythemia vera and leukemia.

- Reduced ocular blood perfusion, caused by systemic hypotension, carotid or ophthalmic artery stenosis, acute blood loss, or elevated intraocular pressure.

Clinical Features

The condition usually manifests as sudden, painless, and non-progressive visual loss, often noted upon waking in the morning. Patients commonly report visual field defects on the nasal side, inferior field, or superior field, with inferior field involvement being the most common. Symptoms typically begin in one eye, though involvement of the second eye may occur months or years later; simultaneous bilateral onset is rare. The disease predominantly affects individuals over 50 years of age and is more common in patients with small optic discs lacking a defined optic cup. Relative afferent pupillary defect may be present.

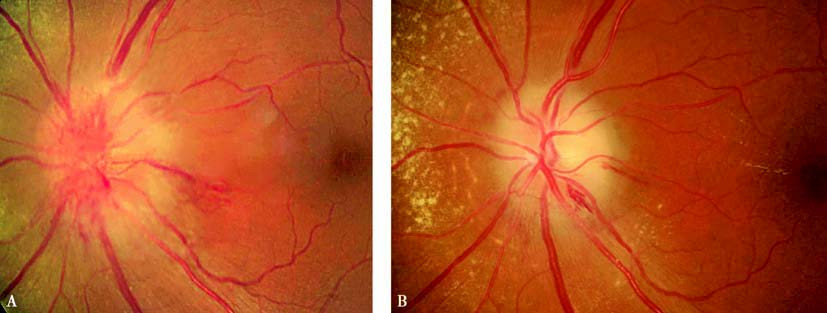

Figure 1 Color photographs of optic discs in AION patients.

A. Day 15 after onset: Grey-white optic disc edema with linear hemorrhages.

B. Day 40 after onset: Reduced edema, pale optic disc, and peripapillary yellow-white punctate exudates.

The optic disc often shows localized or diffuse edema, accompanied by disc hyperemia and peripapillary linear or flame-shaped hemorrhages, and retinal venous dilation may occur. Some patients present with mild serous retinal detachment between the optic disc and macula. After the edema subsides, parts or all of the optic disc may turn pale, and lipid deposits may appear around the disc or in the macular region.

Based on the underlying causes, AION can be categorized into:

- Non-arteritic AION: Often linked with arteriosclerotic changes and occurs primarily in patients aged 40 to 60 years. Risk factors include diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Nocturnal hypotension, especially in patients taking antihypertensive medications, is a common trigger.

- Arteritic AION: Caused by giant cell arteritis (GCA), which is less frequent than non-arteritic AION. This form primarily affects individuals aged 70 to 80 years and features more severe visual loss and optic disc edema compared to the non-arteritic form. Bilateral involvement may occur simultaneously. Laboratory indicators include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR) and C-reactive protein levels. Temporal arteries may exhibit tenderness, lack pulsation, and be palpable as cord-like structures. Complications can include retinal artery embolism or cranial nerve palsy (especially affecting the abducens nerve). When GCA is suspected, temporal artery biopsy is recommended for confirmation.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis can be made based on the patient's medical history and clinical features, supported by visual field tests and fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA). Visual field defects typically appear as arcuate or fan-shaped defects contiguous with the physiological blind spot, corresponding to the affected area of the optic disc. Early-phase FFA shows localized or diffuse delayed filling of the optic disc arteries, while late-phase imaging reveals fluorescein leakage corresponding to visual field defects. Delayed choroidal filling may also be observed. Color Doppler ultrasound of the carotid artery and retrobulbar vessels often reveals decreased blood flow. Continuous 24-hour blood pressure monitoring can identify nocturnal hypotension. Visual evoked potential reveals reduced amplitude and prolonged latency, with amplitude reduction being more prominent. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides detailed visualization of changes in the nerve fiber layer and detachment of the macular neurosensory epithelium.

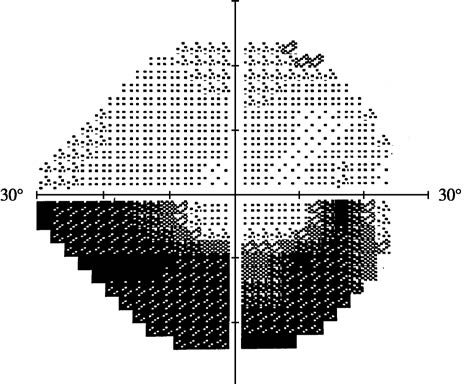

Figure 2 Visual field changes in AION

Arcuate visual field defects adjacent to the physiological blind spot, encircling the central fixation point.

Treatment

Early systemic corticosteroid therapy alleviates optic disc edema and improves vision and visual field defects. Non-arteritic cases are often managed with oral medications, while arteritic cases require immediate high-dose intravenous corticosteroid pulse therapy (as per optic neuritis treatment protocols) to preserve vision and prevent involvement of the contralateral eye.

Treatment should target systemic conditions, particularly measures to prevent and manage nocturnal hypotension.

Microcirculation-enhancing and neurotrophic agents, such as anisodamine, may provide supportive benefits.