Optic neuritis refers to various inflammatory conditions affecting the optic nerve. It is a vision-threatening disease more commonly seen in young and middle-aged individuals. Based on the location of the lesion, it is classified into papillitis (optic disc inflammation), retrobulbar optic neuritis, perineuritis (primarily involving the optic nerve sheath), and neuroretinitis (inflammation involving both the optic nerve and adjacent retina).

Etiology

The etiology of optic neuritis is complex. The most common cause is inflammatory demyelination, but it may also result from infections such as tuberculosis, syphilis, viral infections, or systemic autoimmune diseases. Approximately one-third to half of cases have no identifiable cause.

Inflammatory Demyelination

The exact cause of demyelinating optic neuritis is unclear but is likely related to triggering factors, such as viral infections of the upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tract, psychological stress, or vaccinations. These factors may provoke an autoimmune response, generating autoantibodies that attack the optic nerve myelin and lead to demyelination. Since intact myelin is critical for the rapid transmission of electrical signals in the optic nerve, its loss results in significantly slowed signal transmission, causing severe visual impairment. Over time, partial remyelination may occur, leading to gradual visual recovery. This pathological process is similar to that seen in multiple sclerosis, a central nervous system demyelinating disease. In some cases, the onset of optic neuritis is associated with antibodies against aquaporin-4 (AQP-4), which is concentrated in the foot processes of astrocytes, or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), which is expressed on the surface of oligodendrocytes. Additionally, central nervous system demyelinating disorders such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) may also involve the optic nerve.

Infections

Both local and systemic infections may affect the optic nerve, causing either infectious optic neuritis (direct invasion by the pathogen) or infection-related optic neuritis (immune-mediated damage to the optic nerve).

Local Infections

Infections such as endophthalmitis, orbital cellulitis, sinusitis, otitis media, mastoiditis, and intracranial infections may spread locally to involve the optic nerve.

Systemic Infections

Certain infectious diseases may also lead to optic neuritis. Examples include bacterial infections such as diphtheria, scarlet fever, pneumococcal and staphylococcal pneumonia, dysentery, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, purulent meningitis, and sepsis. Viral infections such as influenza, measles, mumps, herpes zoster, varicella, and novel coronaviruses, as well as spirochetal infections (e.g., Lyme disease, leptospirosis, syphilis) and parasitic infections (e.g., toxoplasmosis, ascariasis, coccidiosis), have all been associated with optic neuritis.

Autoimmune Diseases

Systemic autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener's granulomatosis, Behçet's disease, Sjögren's syndrome, and sarcoidosis may cause nonspecific inflammatory changes in the optic nerve, referred to as autoimmune optic neuropathy.

Clinical Features

Symptoms

Demyelinating optic neuritis often has an acute or subacute onset, with a progressive decline in vision in the affected eye. Severe cases may result in profound vision loss within one to two days, sometimes reducing vision to no light perception. Visual impairment is typically most severe 1–2 weeks after onset. Evidence from Caucasian populations suggests partial spontaneous recovery of vision in some patients approximately two weeks after onset.

Mild cases may manifest primarily as color vision abnormalities or reduced contrast sensitivity. Eye pain, pain with eye movement, or photopsia are common complaints.

Co-occurrence of symptoms such as limb numbness, weakness, bladder or rectal sphincter dysfunction, and balance disturbances may suggest the presence of a central nervous system demyelinating disorder.

Vision loss may worsen with physical exertion or hot baths, a phenomenon known as Uhthoff's sign, possibly associated with elevated body temperature impairing axoplasmic transport in the optic nerve fibers.

The disease typically affects one eye but may involve both eyes. However, pediatric optic neuritis more commonly affects both eyes.

Signs

The affected eye may exhibit sluggish or absent direct pupillary light reflex, while a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) may be seen if the optic nerve is unilaterally or asymmetrically involved.

Funduscopic examination findings depend on the specific clinical subtype:

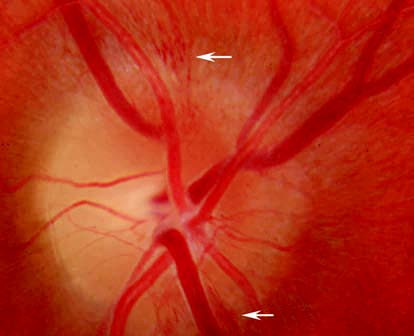

Figure 1 Hyperemia of the optic disc in a patient with disc inflammation.

Papillitis

This is characterized by optic disc hyperemia and swelling, with possible small hemorrhages on or around the optic disc. Some patients may also display mildly dilated and tortuous retinal veins or exudates near the optic disc.

Neuroretinitis

Edema and exudates extend beyond the optic disc to the surrounding retina, often involving the posterior pole.

Retrobulbar Optic Neuritis

Early fundus findings may be unremarkable, but optic disc pallor may develop later in the disease course.

Idiopathic Demyelinating Optic Neuritis

Idiopathic demyelinating optic neuritis (IDON) is reported as the most common type of optic neuritis in studies conducted in Western countries. It typically presents as a unilateral condition with a characteristic course of demyelinating optic neuritis, which is usually self-limiting. Both aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) antibodies and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies are negative. Vision decline persists for less than two weeks, with recovery beginning around three weeks after onset. Most patients achieve normal vision within 1–3 months. Approximately one-third of patients exhibit optic disc edema, while the remaining two-thirds present with retrobulbar optic neuritis. Optic neuritis is often the first manifestation of multiple sclerosis (MS), and between one-third and over half of patients with IDON eventually progress to MS, particularly those with demyelinating lesions in the brain's white matter. For this reason, IDON is also referred to as multiple sclerosis-related optic neuritis (MS-ON).

Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) are autoimmune disorders of the central nervous system, characterized by recurrent optic neuritis and longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM). The 2015 international diagnostic criteria for NMOSD include optic neuritis with AQP-4 antibody positivity as part of the spectrum. NMOSD-associated optic neuritis (NMOSD-ON) is more prevalent in Asian populations and has clinical features distinct from IDON, including a higher frequency of bilateral involvement, less severe eye pain, more profound visual impairment with poor recovery, and a high recurrence rate of up to 80% within five years. Acute spinal cord involvement may precede, follow, or occur simultaneously with visual decline, manifesting as paraplegia, sensory and sphincter dysfunction, and, in severe cases, respiratory muscle paralysis.

MOG Antibody-Associated Disorders and Limited Optic Neuritis

The pathogenesis of MOG antibody-associated optic neuritis (MOG-ON) differs from multiple sclerosis and NMOSD. MOG-ON is commonly observed in pediatric populations and in recurrent optic neuritis. It frequently involves both eyes, with MOG antibody positivity, AQP-4 antibody negativity, and good response to corticosteroid treatment. Recovery is rapid, though steroid dependence may occur in some cases. Despite the tendency for recurrences, the overall prognosis is favorable.

Infectious and Infection-Related Optic Neuritis

The clinical features of infectious and infection-related optic neuritis, as well as autoimmune optic neuropathy, resemble those of demyelinating optic neuritis. However, these conditions typically lack the natural remission and relapse pattern of demyelinating optic neuritis. Improvement is often achieved through treatment of the underlying cause, sometimes supplemented by high-dose corticosteroid therapy.

Diagnosis

Medical History and Ocular Findings

The clinical diagnosis is made based on the patient’s age at onset, the characteristics of vision loss, the presence of eye pain, pupillary abnormalities, fundus changes, and disease progression. It is important to ascertain whether the patient has a history of similar episodes or an underlying systemic disease such as multiple sclerosis.

Visual Field Testing

Various types of visual field defects may be observed, with central scotomas and concentrically constricted visual fields being the most typical findings.

Visual Evoked Potential (VEP)

Findings often include prolonged P100 wave latency and/or reduced amplitude. In retrobulbar optic neuritis, where funduscopic changes are absent, VEP proves particularly valuable in assessing visual pathway function and distinguishing optic neuropathy from optic malingering.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

OCT provides quantitative analysis of retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness, optic cup morphology, and macular ganglion cell layer thickness. In MS-ON and NMOSD-ON, significant thinning of the macular ganglion cell complex and inner plexiform layer is more sensitive than RNFL thinning for assessing the degree of optic nerve damage. OCT is useful for diagnosis, differential diagnosis, monitoring disease progression, prognostication, and treatment planning in optic neuritis.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Orbital MRI during the acute phase may reveal optic nerve swelling, thickening, and demyelinating lesions, with an abnormal rate as high as 92%. These findings support the diagnosis of demyelinating optic neuritis but are not specific, as similar changes can occur in ischemic, infectious, or other inflammatory optic neuropathies. Chronically, optic nerve atrophy and thinning may be observed, along with widening of the subarachnoid space around the optic nerve. Orbital MRI is also valuable for identifying other optic nerve pathologies, such as optic nerve tumors, orbital inflammatory pseudotumors, or optic nerve sarcoidosis. Cranial MRI is essential for evaluating the presence of demyelinating plaques in white matter, aiding in the early diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and NMOSD. It also helps to differentiate compressive optic neuropathies caused by lesions, such as sellar tumors, and to assess conditions like sinusitis, providing insights for differential diagnosis.

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis

CSF examination helps to confirm evidence of demyelination in the optic nerve or central nervous system while excluding other causes such as infectious, tuberculous, or syphilitic inflammation. Findings such as elevated protein levels without corresponding cellular pleocytosis, increased IgG synthesis, oligoclonal band positivity, and elevated myelin basic protein levels suggest demyelination but provide limited predictive value for the conversion of optic neuritis to multiple sclerosis. Owing to its invasive nature, CSF analysis should only be performed when clinically indicated.

Additional Testing

For acute optic neuritis with atypical symptoms or clinical history, additional tests might include serological evaluations for infections like syphilis or HIV, immunological markers such as antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies, anti-ENA profiles, or antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Testing for AQP-4 and MOG antibodies in blood and/or CSF, as well as genetic testing in selected cases, plays a critical role in diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment planning.

Differential Diagnosis

Pseudopapilledema

The optic disc may appear red and slightly elevated, but the elevation usually does not exceed 1–2 diopters and remains stable throughout life. There is no peripapillary hemorrhage or exudation. Visual acuity, whether uncorrected or corrected, is typically normal. Fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA) reveals no fluorescein leakage from the optic disc.

Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (AION)

Vision loss or visual field defect is often noticed suddenly upon waking in the morning and does not progress. Eye pain is uncommon. The optic disc typically exhibits localized or diffuse edema, often accompanied by hemorrhage at the disc margins. Visual field defects, often arcuate or sector-shaped and frequently connected to the physiological blind spot, are more common than central scotomas. The condition primarily affects middle-aged and elderly individuals. Non-arteritic AION often has a history of systemic vascular risk factors, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, or long-term smoking. Arteritic AION is associated with symptoms of temporal arteritis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates and C-reactive protein levels.

Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON)

Onset typically occurs between the teenage years and the twenties, with males being far more affected than females. This mitochondrial hereditary disease involves bilateral optic neuropathy in 90–95% of cases due to primary missense mutations in mitochondrial DNA, particularly at positions 11,778, 14,484, or 3,460. Over 40 additional secondary mutations have recently been identified. Both eyes are affected either simultaneously or sequentially, leading to acute or subacute painless visual decline, central visual field defects, and color vision abnormalities. In the acute phase, optic disc hyperemia and dilated capillaries appear without fluorescein leakage. This is followed by optic nerve atrophy. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) often shows atrophy primarily affecting the papillomacular bundle. The visual prognosis is generally poor, particularly for the 11,778 mutation. Clinical trials for gene therapy are currently underway.

Toxic or Metabolic Optic Neuropathy

Progressive, bilateral, and painless severe vision loss is common. It may occur secondary to chronic tobacco use, chronic alcohol toxicity, acute methanol poisoning, severe malnutrition, drug toxicity (e.g., ethambutol, chloroquine, isoniazid, chlorpropamide), heavy metal poisoning, or conditions such as severe anemia.

Other Causes:

Conditions such as compressive optic neuropathy caused by anterior cranial fossa tumors, optic disc edema due to idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and psychogenic vision loss (e.g., hysteria or malingering) may mimic optic neuritis and warrant careful differentiation.

Treatment

Treatment for optic neuritis emphasizes addressing the underlying cause, preserving visual function to the greatest extent possible, and preventing, mitigating, or delaying further damage to the nervous system. Correct diagnosis of optic neuritis is essential, followed by investigations into the nature and etiology of the condition to guide appropriate targeted therapy. It is particularly important to recognize that visual dysfunction may represent one of the symptoms of an underlying systemic disease. If any related systemic condition is suspected, referral to relevant specialties such as neurology, rheumatology, infectious diseases, or otolaryngology for comprehensive treatment is advised.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for acute non-infectious optic neuritis. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) is recommended as the initial therapy, followed by a tapering course of oral prednisone or an equivalent dose of methylprednisolone. Peribulbar or retrobulbar injections are generally not recommended.

Although some cases of idiopathic demyelinating optic neuritis (IDON) may resolve spontaneously, corticosteroid treatment accelerates recovery of visual function and reduces recurrence rates. For severe IDON or bilateral cases, as well as acute optic neuritis with AQP-4 or MOG antibody positivity, IVMP is recommended. The typical dosage is intravenous methylprednisolone at 1 g/day (or 20–30 mg/kg/day for children) for 3–5 days, followed by oral prednisone at 1 mg/kg/day or an equivalent dose of methylprednisolone. Due to ethnic differences, patients with optic neuritis exhibit a 40% conversion rate to NMOSD within five years compared to only 4.8% for multiple sclerosis (MS). For patients with monocular IDON already in the recovery phase, the routine use of IVMP is not strongly recommended, and initiating therapy with oral prednisone at 1 mg/kg/day is discouraged. Corticosteroids can be rapidly tapered in IDON or MS-ON, while other subtypes of optic neuritis require a slow taper over at least 4–6 months to minimize the risk of early relapse.

Immunosuppressive Therapy

Immunosuppressive agents are mainly used to reduce the recurrence of optic neuritis and prevent or mitigate damage to the spinal cord and brain. Commonly used immunosuppressants include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and rituximab. Early initiation of immunosuppressive therapy (IST) is recommended for NMOSD-ON with AQP-4 antibody positivity. Recurrent IDON, recurrent MOG-ON, and optic neuritis with persistent MOG antibody positivity are indications for immunosuppressive therapy as well.

Plasma Exchange and Immunoadsorption Therapy

Plasma exchange or immunoadsorption therapy is recommended for severe demyelinating optic neuritis with acute stage IVMP treatment failure or bilateral involvement (with a best-corrected visual acuity ≤0.1), particularly for patients with AQP-4 antibody positivity. Treatment is typically administered 5–7 times, every other day. Compared to plasma exchange, immunoadsorption therapy offers the advantage of selectivity, as it does not require plasma replacement. Instead, the patient’s plasma is passed through an immunoadsorption column to remove antibodies and immune complexes, after which the treated plasma is returned to the patient. However, immunoadsorption targets all antibodies, including AQP-4 antibodies.

Immunoglobulin Therapy

Immunoglobulin therapy is an alternative option for treating acute-stage demyelinating optic neuritis, particularly in cases unresponsive to IVMP or cases that continue to worsen, as well as in patients with contraindications to other treatments. Possible treatment regimens include:

- Daily administration of 0.4 g/kg for 5 consecutive days.

- A total dose of 2 g/kg divided into two infusions.

Antibiotics

Early initiation of appropriate, full-course, and adequate doses of antibiotics is necessary for infectious optic neuritis with identified pathogens. For syphilitic optic neuritis, treatment should follow the protocol for neurosyphilis management. Tuberculous optic neuritis requires standard anti-tuberculosis therapy. Lyme disease-related optic neuritis is treated with prolonged ceftriaxone therapy, while fungal sinusitis-related optic neuritis requires antifungal therapy after surgical intervention.

Neurotrophic Agents

Neurotrophic medications such as B vitamins and creatine may provide some adjunctive benefits for optic neuritis treatment.