Primary retinitis pigmentosa (RP) refers to a group of hereditary ocular disorders characterized as degenerative dystrophies affecting the photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The exact pathogenesis remains incompletely understood and may involve genetic and environmental factors leading to photoreceptor degeneration and cell death. Recent studies suggest that inflammation and innate immunity also play crucial roles in the onset and progression of the disease. Clinically, RP is marked by night blindness, progressive constriction of the visual field, pigmentary retinal changes, and impaired photoreceptor function as shown on electroretinography (ERG). The disease demonstrates various inheritance patterns, including X-linked, autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, or sporadic forms. While most cases involve both eyes, a small number present with unilateral involvement. The age of onset, disease severity, and progression vary among patients. Symptoms typically begin before the age of 30, with childhood or adolescence being common periods of onset. Symptoms worsen during puberty, and severe visual impairment develops in middle age or older adulthood due to macular involvement, often leading to blindness.

Clinical Features

Night blindness is the earliest symptom and progressively worsens over time.

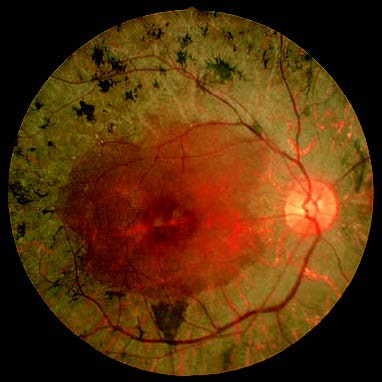

The optic disc appears waxy yellow, and retinal vessels, particularly the arterioles, are noticeably narrowed. The retina appears grayish, with pigment deposits resembling bone spicules observed near the equatorial region around the retinal vessels. These pigmentary changes spread towards both the posterior pole and peripheral retina.

Figure 1 Fundus photograph of the right eye with primary retinitis pigmentosa.

The optic disc appears waxy yellow, the retinal vessels are attenuated, and the retina has a grayish tone. Bone-spicule–like pigmentation is seen near the equatorial retinal vessels.

Other frequent findings include posterior subcapsular cataract–like opacity in the lens. In later stages, macular edema and epiretinal membrane may occur.

Diagnosis

Visual Field Testing

In the early stages, visual fields show a ring scotoma that gradually expands toward the center and periphery, leading to progressive visual field constriction. In advanced stages, tunnel vision develops, though central vision may be preserved for prolonged periods. Symptoms are typically symmetric between both eyes.

Fundus Autofluorescence Imaging (FAF)

This technique reveals additional lesion areas not visible upon funduscopic examination, characterized by hypoautofluorescence with mottled hyperautofluorescent changes.

Fundus Fluorescein Angiography (FFA)

Due to widespread degeneration and atrophy of the RPE, fundus imaging shows diffuse speckled hyperfluorescence. Severe cases reveal large areas of window defects, while pigmented regions block fluorescence. Approximately 75% of cases show dye leakage, particularly from the optic disc, vascular arcades, and macula, sometimes accompanied by cystoid macular edema. Late-stage cases may present with choroidal capillary atrophy that appears as patchy hypofluorescence near the equator.

Electrophysiology

ERG is markedly abnormal early in the disease, showing reduced amplitudes and delayed latencies or even the complete absence of waveforms. Electrooculography (EOG) is also abnormal.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

Retinal and choroidal thinning are observed. In late stages, macular cystoid edema, epiretinal membrane, or macular atrophy may develop.

Treatment

Currently, no effective treatment is available. The therapeutic benefits of nutritional supplements, vasodilators, and antioxidants (such as vitamin A and vitamin E) remain uncertain. Avoidance of bright light is recommended. Patients with low vision may consider assistive devices. Emerging approaches like gene therapy, stem cell therapy, and vision prostheses offer hope for future clinical advancements.