A macular hole refers to a localized full-thickness defect in the neurosensory retina within the macular region. Based on the etiology, macular holes can be classified as secondary or idiopathic. Secondary macular holes may result from ocular trauma, macular degeneration, chronic cystoid macular edema, or high myopia, among other causes. Idiopathic macular holes typically occur in relatively healthy eyes of older individuals, more commonly in women. The exact cause remains unclear, but the tangential traction exerted by contraction of the posterior vitreous cortex on the macula is thought to play a significant role.

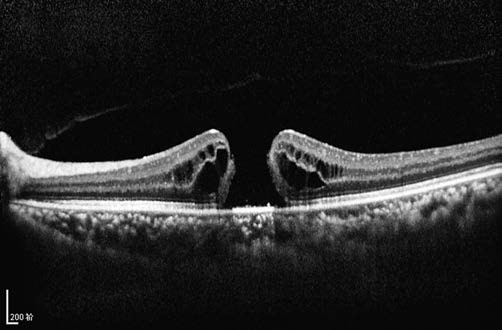

Figure 1 OCT image of a macular hole in the left eye

The macular hole (Stage IV) shows full-thickness disruption of the neurosensory retina. Detached posterior vitreous cortex is faintly visible, and the absence of an "epiretinal membrane" over the hole is noted.

Based on the mechanism of formation, Gass categorized idiopathic macular holes into four stages:

- Stage I represents a pre-hole stage, characterized by focal detachment of the fovea. Mild visual decline occurs, with yellowish spots or rings observed in the fovea. Spontaneous resolution is observed in approximately half of the cases.

- Stages II to IV involve full-thickness macular holes.

- Stage II holes are less than 400 μm in diameter and typically appear eccentric, with configurations such as crescent, horseshoe, or oval shapes.

- Stage III holes measure more than 400 μm and appear as full-thickness round holes, with the posterior vitreous cortex still adhered to the macula.

- Stage IV holes are larger and accompanied by posterior vitreous detachment, with Weiss rings sometimes visible.

Patients with full-thickness macular holes experience significant visual loss, commonly ranging from 0.05 to 0.2 (decimal Snellen acuity), and report central scotomas. On slit-lamp biomicroscopy using a fundus contact lens, an interruption of the light reflex at the site of the macular hole may be observed. OCT imaging provides a detailed view of the relationship between the posterior vitreous cortex and the macular hole, as well as tissue changes associated with the macular hole, serving as the "gold standard" for diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

Macular holes secondary to high myopia carry a higher risk of retinal detachment, necessitating surgical interventions such as vitrectomy. Idiopathic macular holes typically do not lead to retinal detachment, and over half of Stage I cases may close spontaneously, allowing observation as an option. Surgical treatment, such as vitrectomy, may be considered for Stage II and above. In cases of chronic or large macular holes, surgical closure may be achieved; however, significant visual improvement is often not attainable.