Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) is commonly seen in healthy young to middle-aged men (25–50 years old). The condition may affect one or both eyes and typically presents as a self-limiting disease, although recurrences can occur.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The exact cause of CSC is unknown. The choroidal vasculature is thought to be the primary site of pathology. The current understanding suggests that increased permeability of choroidal capillaries leads to serous detachment of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which in turn disrupts the RPE barrier function, resulting in RPE leakage and serous retinal detachment at the posterior pole. The specific factors causing increased permeability of the choroidal capillaries remain controversial. Studies have shown elevated serum catecholamine levels in affected individuals. Additionally, both exogenous and endogenous corticosteroids have been implicated. Individuals with type A personalities appear to be more susceptible. Triggers or exacerbating factors include emotional fluctuations, psychological stress, pregnancy, and high-dose systemic corticosteroid usage.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients often experience decreased vision in the affected eye, along with symptoms such as darkening, distortion, reduction, or recession of perceived images. These symptoms are accompanied by a central relative scotoma. Fundoscopic examination reveals a serous detachment in the macula, typically 1–3 disc diameters (DD) in size, with a round or oval flat plaque-like appearance. A curved halo along the detachment margin and the absence of the foveal light reflex are also observed. In later stages of the disease, numerous fine yellow-white spots may appear beneath the retina in the detachment area.

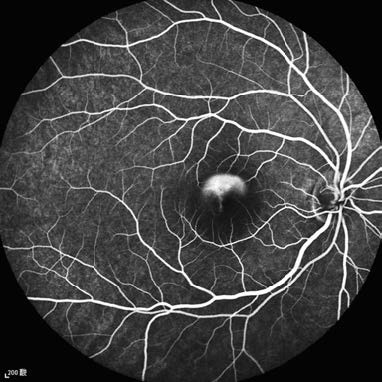

Fluorescein angiography (FFA) shows one or more fluorescein leakage points within the serous retinal detachment area during the venous phase. These appear as a "smokestack" pattern ascending upward or a "inkblot" pattern diffusing outward. In cases of severe leakage, fluorescein pooling in the subretinal fluid may outline the detachment area in later stages. Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) reveals abnormal dilation and hyperperfusion of large choroidal vessels. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI-OCT) or swept-source OCT typically shows increased choroidal thickness in the affected eye.

Figure 1 Fluorescein fundus angiography of the right eye with central serous chorioretinopathy

A fluorescein leakage point is observed within the serous retinal detachment area during the venous phase, demonstrating a "smokestack" pattern of expansion.

Most cases resolve spontaneously within 3–6 months, with visual recovery. However, symptoms such as distorted and reduced image size may persist for more than a year. Some patients with recurrent episodes or chronic unresolved disease may develop complications such as choroidal neovascularization (CNV) or polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV). Increasingly, clinical practice incorporates the use of combined OCT and OCT angiography (OCTA) to detect CNV or PCV.

Treatment

CSC is generally a self-limiting condition and may be observed in its early stages. Corticosteroids and vasodilators are contraindicated. The effectiveness of oral mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (eplerenone or spironolactone) requires further validation through additional research.

Half-dose verteporfin photodynamic therapy (PDT) effectively promotes subretinal fluid absorption, reduces choroidal thickness, and decreases choroidal vascular hyperpermeability, making it a viable treatment option for chronic CSC. Subthreshold micropulse laser therapy is another possible treatment. If the leakage point lies outside the central fovea (at least 500 μm away from the foveal center), focal laser photocoagulation can encourage RPE barrier repair and facilitate subretinal fluid absorption. However, laser photocoagulation carries a potential risk of inducing CNV. If CNV or PCV is present, anti-VEGF therapy may be considered.