Etiology

The primary cause of branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) is compression of the vein by a thickened and sclerotic arterial wall at arteriovenous crossing points. Local or systemic inflammation is another contributing factor.

Clinical Manifestations

The affected eye experiences varying degrees of vision loss. Blockage occurs most commonly at the arteriovenous crossing points of the first to third branches of the retinal vein, though occlusion can also occur in macular venules. The superotemporal branch is most frequently affected, while occlusion in the nasal branches is less common. Anatomical variations may result in occlusion involving either the upper or lower hemispheric branches. Affected veins become tortuous and dilated, and intraretinal hemorrhages, retinal edema, and cotton wool spots are present in the drainage area downstream from the blocked vein. Superotemporal branch occlusion often involves the macula, leading to macular edema, which can cause significant vision loss. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is used to examine and quantify the extent of macular edema.

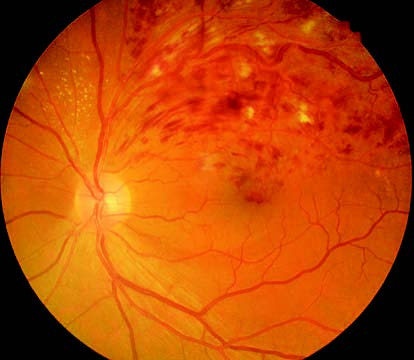

Figure 1 Color fundus photograph of BRVO in the left eye

The superotemporal branch vein in the left eye is tortuous and dilated. Intraretinal hemorrhages, retinal edema, and cotton wool spots are visible in the drainage area of the obstructed vein.

According to fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA), BRVO is classified into two types:

- Non-Ischemic Type: Capillary dilation and leakage are seen in the area of occlusion, with collateral circulation forming between venules proximal and distal to the obstruction. In hemispheric BRVO, collateral vessels appear near the optic disc. There are no significant capillary non-perfusion areas.

- Ischemic Type: Large areas of capillary non-perfusion (greater than five disc areas) are observed, potentially involving the macular area. Visual prognosis is poor. Within 3–6 months from onset, retinal neovascularization often develops, leading to complications such as vitreous hemorrhage and even tractional or rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

Treatment

Management should begin with addressing systemic diseases contributing to the condition. Corticosteroid therapy may be appropriate in the presence of vascular inflammation. Macular edema and retinal neovascularization are the main causes of vision loss in BRVO. Intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents is considered the first-line therapy for macular edema, while intravitreal injection of dexamethasone implants is another option. Focal or grid laser photocoagulation can serve as a second-line treatment for macular edema secondary to non-ischemic BRVO.

For eyes with extensive areas of non-perfusion or retinal neovascularization, scatter laser photocoagulation in ischemic areas is administered to inhibit neovascularization or encourage regression of newly formed vessels. In cases of significant amounts of non-resolving vitreous hemorrhage and/or retinal detachment, vitrectomy combined with intraocular photocoagulation is required.