Etiology

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) often occurs in the region of the optic nerve lamina cribrosa, where the space is considerably narrow, resulting in compression on the central retinal vein (CRV) by the crowded nerve fibers. Additionally, the central retinal artery (CRA) and CRV are located in close proximity at the lamina cribrosa, making this area or the neighboring portion of the CRV prone to thrombosis. Factors that promote thrombus formation include:

- Vascular Wall Changes: Hypertension and CRA sclerosis exert compressive pressure on the CRV, which are the most common risk factors and are typically seen in patients over 50 years of age. Inflammation of the CRV, causing wall edema, intimal damage, and endothelial cell proliferation, may also narrow the lumen and obstruct blood flow, more commonly affecting patients under 45 years of age.

- Hemorheological Changes: Systemic diseases, particularly diabetes, can lead to increased blood viscosity, elevated platelet count and aggregation, and higher thromboxane B2 levels.

- Hemodynamic Changes: Conditions such as cardiac insufficiency, carotid artery stenosis or occlusion, and giant cell arteritis can result in reduced retinal perfusion pressure or impaired venous outflow. Additionally, localized ocular factors such as elevated intraocular pressure and optic disc drusen can impede venous blood return in the CRV. CRVO has a complex etiology and is often the result of multiple contributing factors.

Clinical Manifestations

CRVO can occur in individuals of any age, with most cases involving a single eye. Vision loss of varying severity is common. Fundus examination typically reveals retinal vein tortuosity and dilation in all quadrants, flame-shaped hemorrhages along the retinal veins, optic disc and retinal edema, and pronounced macular edema that often progresses to cystoid macular edema over time. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides quantitative assessment of macular edema. Based on clinical features and prognosis, CRVO is classified into ischemic and non-ischemic types.

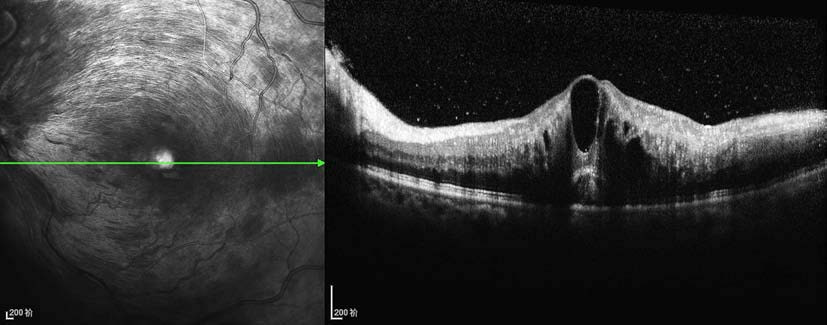

Figure 1 OCT image of cystoid macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion in the left eye

Severe cystoid macular edema is observed, with multiple fluid-filled cystic spaces between retinal layers.

Ischemic CRVO is frequently associated with cystoid macular edema and carries a poor prognosis. Within 3–4 months of onset, iris neovascularization and neovascular glaucoma are common complications.

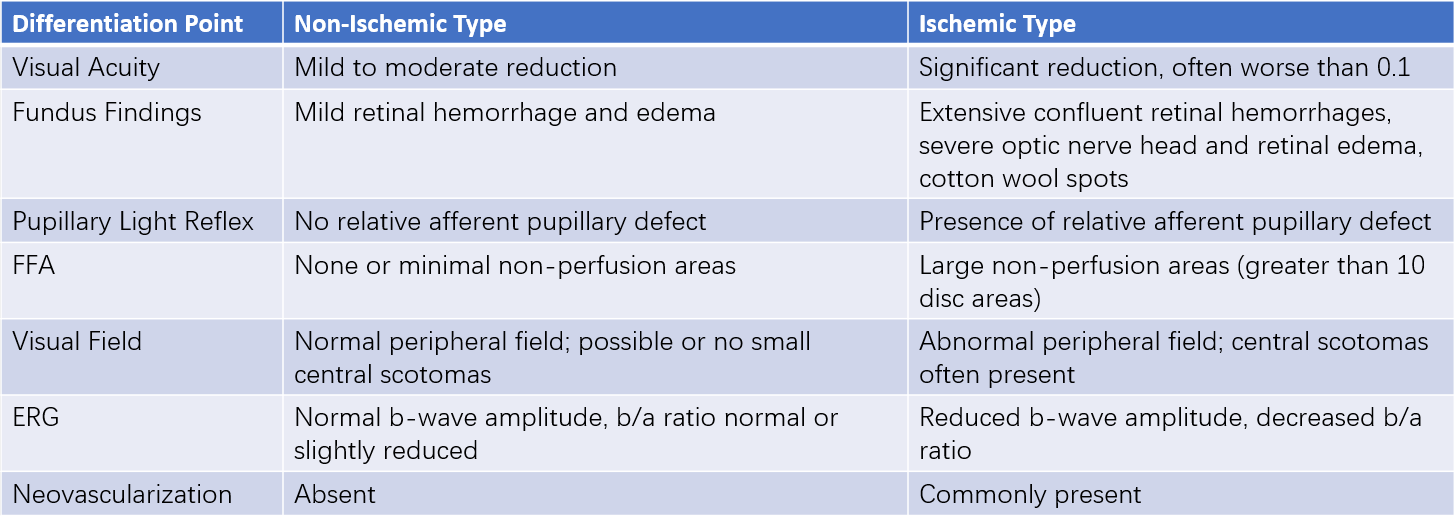

Table 1 Classification and characteristics of CRVO

Treatment

Currently, there is no effective medication for CRVO. Hemostatics, anticoagulants, and vasodilators are generally considered unsuitable. Management focuses on identifying and addressing systemic causes, while locally, the emphasis is placed on preventing and treating complications. For macular edema, intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents has become the first-line therapy due to its proven efficacy and safety. This approach effectively reduces edema and improves visual acuity, though multiple injections are often required, and recurrence is common. Intravitreal injection of dexamethasone implants also shows significant efficacy but carries risks of steroid-induced cataracts and glaucoma, with some patients experiencing recurrence.

The prognosis for non-ischemic CRVO is typically better; however, about 34% of cases transition to ischemic CRVO within a three-year follow-up period. Patients with ischemic CRVO require more frequent follow-ups. Peripheral retinal assessment is important, and if there is evidence of non-perfusion, scatter laser photocoagulation in the non-perfused areas is recommended. When anterior segment neovascularization and neovascular glaucoma occur, panretinal photocoagulation combined with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents offers a more appropriate treatment. Late-stage complications such as vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, and neovascular glaucoma may necessitate vitrectomy or glaucoma surgery as part of a comprehensive treatment approach.