Etiology

The main causes of central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) include:

- Atherosclerosis: Most cases involve atherosclerotic embolism at the lamina cribrosa level of the central retinal artery (CRA).

- Central Retinal Artery Spasm: Common in young individuals with unstable vascular tone, early-stage hypertension patients, or elderly individuals with atherosclerosis.

- Periarteritis of the Central Retinal Artery: Associated with systemic vasculitis.

- External Compression of the CRA: Causes include glaucoma, buried optic disc drusen, orbital trauma, retrobulbar tumors, or compression from retrobulbar hemorrhages.

- Coagulopathies: Conditions such as S protein or C protein deficiencies, antithrombin III deficiency, sticky platelet syndrome, pregnancy, or oral contraceptive use.

- Embolism: Emboli can be detected in the retinal arterial system in 20–40% of CRAO cases. Based on the source, emboli are categorized as:

- Cardiogenic Emboli: Including calcified emboli, vegetations, thrombi, and debris from cardiac myxomas.

- Carotid or Aortic Source Emboli: Including cholesterol emboli, fibrin emboli, and calcified emboli.

- Other Sources: Drug-related emboli, such as those caused by inferior turbinate or retrobulbar injection of prednisolone. Recent years have also reported cases of ophthalmic artery embolism or CRAO resulting from minimally invasive facial injections of hyaluronic acid for cosmetic purposes.

Clinical Manifestations

CRAO usually presents as a sudden, painless, and significant decline in vision in the affected eye. Some cases may have a history of transient blackouts (amaurosis fugax) preceding the event. About 90% of CRAO cases have an initial visual acuity between counting fingers and light perception. The pupil of the affected eye is dilated, with a markedly sluggish direct light reflex while the indirect light reflex remains intact.

The retina shows diffuse edema and cloudiness, particularly in the posterior pole, where it appears pale or milky-white with a cherry-red spot at the fovea. The retinal arteries and veins become attenuated, and in severe cases, the retinal arteries and veins may exhibit segmented blood columns (“boxcarring”).

Figure 1 Color fundus photography of central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) in the right eye

The retina appears pale, with attenuated arteries and veins, and a cherry-red spot at the fovea.

Weeks after onset, retinal edema resolves, the cherry-red spot disappears, and the optic disc becomes pale with narrowed retinal arteries. Around 25% of acute CRAO cases have a cilioretinal artery supplying part or the entirety of the papillomacular bundle, producing a wedge-shaped, orange-red area within the affected vascular territory.

Figure 2 Cilioretinal artery-supplied area in acute CRAO of the right eye

An "orange-red wedge-shaped" area corresponding to the cilioretinal artery's vascular supply.

Diagnosis

Fluorescein Fundus Angiography (FFA)

Within hours to a few days of occlusion, the retinal arterial filling time is markedly delayed, with the appearance of "plasmatic flow" (representing the leading edge of fluorescein in the artery). The fluorescein column may appear narrowed, segmented, or pulsatile. Weeks later, as retinal arterial flow recovers, FFA findings may normalize.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

The inner retinal layers display edema and thickening with high-reflective signals in the acute phase.

Differential Diagnosis

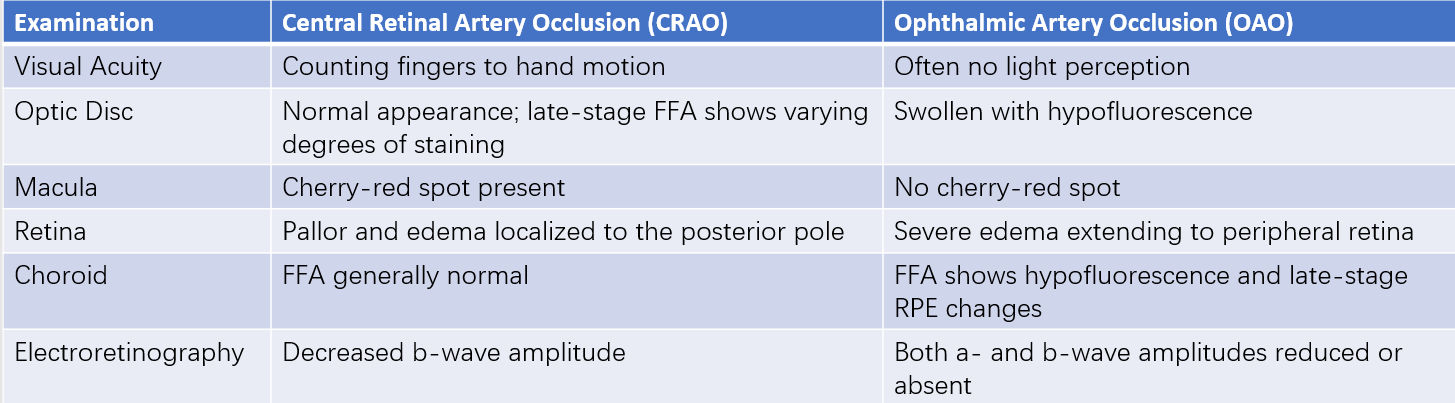

Ophthalmic artery occlusion (OAO) is often misdiagnosed as CRAO. Key points of differentiation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Key differentiation points between CRAO and ophthalmic artery occlusion (OAO)

Treatment

CRAO is a medical emergency requiring urgent intervention. Current treatment strategies involve:

- Lowering Intraocular Pressure: Using methods such as ocular massage, anterior chamber paracentesis, or oral acetazolamide to facilitate the migration of emboli into smaller distal vessels.

- Respiratory Gas Therapy: Administration of a mixture of 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide or hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

- Vasodilatory and Anticoagulant Therapy: Retrobulbar injections (e.g., tolazoline) or systemic vasodilators (e.g., amyl nitrite or sublingual nitroglycerin); systemic anticoagulants like aspirin.

- Corticosteroids for Giant Cell Arteritis: In suspected cases, systemic corticosteroids are administered to prevent involvement of the unaffected eye.

- Thrombolytic Therapy: Intravenous or intra-arterial administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) has been reported in some cases.

These treatment modalities currently lack high-quality evidence from randomized clinical trials. Identifying systemic risk factors is critical, as CRAO significantly increases the risk of concurrent cardiocerebrovascular ischemic disease. Immediate systemic evaluation is essential after an acute CRAO episode.