Keratoconus is a congenital developmental disorder characterized by localized, cone-shaped protrusion of the cornea accompanied by thinning of the corneal stroma in the protruded area. Its etiology is associated with genetic factors, though the genetic background and inheritance patterns are complex. It may be accompanied by other congenital diseases, such as congenital cataracts, Marfan syndrome, aniridia, retinitis pigmentosa, and others. Recent studies suggest a close relationship between this condition and eye rubbing caused by allergic conjunctivitis.

Clinical Manifestations

Keratoconus often presents in adolescence and is usually bilateral, though the onset in each eye may occur at different times, and the severity may vary between eyes. It is characterized by progressively worsening vision. In the early stages, vision can be corrected with spectacles, but in later stages, due to irregular astigmatism, correction requires the use of contact lenses. The hallmark sign is a conical protrusion of the corneal center or paracentral area, which may appear round or oval in shape. Corneal thinning is most pronounced at the apex of the cone. The conical protrusion leads to severe irregular astigmatism and high myopia, resulting in significant visual decline, which may not improve adequately even with contact lenses.

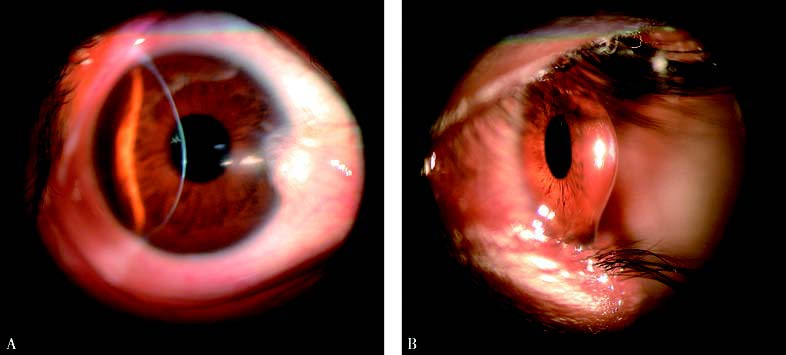

Figure 1 Keratoconus

A. Frontal view: Central conical protrusion of the cornea with significant thinning observed under a slit-lamp microscope.

B. Lateral view: Central conical protrusion of the cornea, appearing round or oval in shape. The area of greatest thinning in the corneal stroma is located at the apex of the cone.

With cobalt blue light illumination, some patients exhibit a brownish Fleischer ring at the base of the cone, caused by deposition of iron in the tears. Deep corneal stroma may show vertical Vogt striae due to folds in the stromal lamellae, which are parallel to the steeper astigmatic axis of the cone. Gentle pressure on the corneal surface may cause these striae to temporarily disappear. When the affected eye looks downward, Munson's sign, a V-shaped indentation of the lower eyelid caused by the cone, may be observed. Further progression can result in rupture of the posterior limiting lamina, leading to acute keratoconus with sudden corneal edema and significant vision loss. Acute corneal edema typically resolves within 6–8 weeks, leaving focal corneal opacities in the central area. Long-term contact lens use can cause corneal surface abrasion, leading to scarring at the cone apex or subepithelial tissue proliferation. These opacities may cause severe glare and further visual impairment.

Diagnosis

Classical cases of keratoconus are not difficult to diagnose. However, diagnosis can be challenging in the early stages when clinical manifestations are not typical. Corneal topography is currently the most effective method for early diagnosis. It reveals distortion of the central corneal topography with steepening in the inferotemporal quadrant. As the disease progresses, steepening extends sequentially to the inferonasal, superotemporal, and superonasal quadrants. Routine corneal topography examination is recommended in adolescents with suspected progressive myopia or astigmatism.

Treatment

In the early and middle stages, vision can be corrected with spectacles or rigid gas-permeable (RGP) contact lenses. When vision cannot be corrected, or if the condition progresses rapidly, corneal transplantation becomes necessary. Both penetrating keratoplasty and deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty are effective surgical options, providing improved vision. However, for patients without abnormalities in the corneal endothelial layer, deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty is usually preferred. In recent years, ultraviolet light and riboflavin cross-linking therapy has shown promising results, though long-term outcomes require further evaluation.