Herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) refers to corneal infections caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV). Also known as simplex keratitis, it is a highly prevalent disease and represents the leading cause of corneal blindness. Clinically, it is characterized by recurrent episodes that progressively worsen corneal opacity, eventually resulting in blindness.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

HSV is a DNA virus, with humans serving as its sole natural host. HSV exists in two serotypes, with HSV-1 being the most common cause of ocular and oral infections, whereas HSV-2 accounts for a smaller proportion of infections.

HSV infections can be classified as primary or recurrent. Primary infections typically occur in infants and young children. Following primary infection, HSV remains latent in the trigeminal ganglion. HSV can establish latency in the sensory neurons of the trigeminal ganglion following primary HSV infection in any tissue innervated by the branches of the trigeminal nerve, including skin and mucosa. In adults, recurrent HSV infection is far more common, with seropositivity for HSV-1 antibodies ranging between 50% and 90% in the general population. Recurrent HSV infection originates from the reactivation of latent virus, though most cases do not present with clinical symptoms. Recent research has indicated that, in addition to the trigeminal ganglion, corneal tissue may also serve as a site of HSV latency, as evidenced by the cultivation of HSV from corneal tissue removed from chronic HSK patients with no signs of recurrent infection. Furthermore, viral DNA sequences can be detected in iris tissue and tear samples via PCR or in situ hybridization (ISH), suggesting that HSV may also establish latency in other tissues.

Reactivation of latent HSV forms the basis of recurrent infection. Reactivation often occurs when immunity is compromised, such as during fever from a cold, systemic or local administration of corticosteroids, or immunosuppressants. Reactivated HSV migrates along retrograde axoplasmic flow in the trigeminal nerve to the corneal tissue, causing recurrent HSK.

Clinical Manifestations

Primary HSV Infection

More than 94% of infants infected with HSV remain asymptomatic, and symptomatic cases typically manifest in the lips, with ocular involvement being relatively rare. Children with symptomatic infection may exhibit systemic fever, preauricular lymphadenopathy, herpes labialis, or skin lesions. Manifestations during this phase are often self-limiting. Ocular involvement includes acute follicular conjunctivitis, membranous conjunctivitis, herpetic eyelid lesions, and punctate or dendritic keratitis. Dendritic keratitis associated with primary infection is characterized by shorter branches, a later onset, and a shorter duration. Primary infection mainly affects the corneal epithelium and typically presents atypically. Less than 10% of affected children develop stromal keratitis or uveitis.

Recurrent HSV Infection

In contrast to primary infection, recurrent HSK usually demonstrates clear clinical features. Differences in viral cytotoxicity and immune response to infection give rise to varied manifestations. Recurrent HSK is further classified into different types based on clinical presentation.

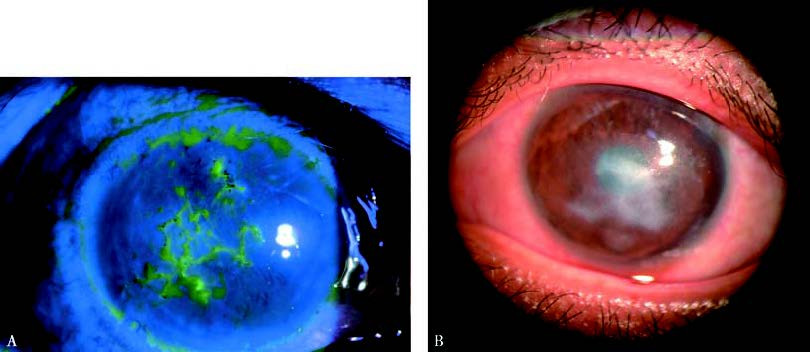

Table 1 Classification of HSK

Epithelial Keratitis

Over 2/3 of HSK cases fall under epithelial keratitis. In the early stages, the corneal epithelium may exhibit pinpoint, gray-white, nearly transparent, slightly elevated vesicles that appear punctate, linearly arranged, or clustered. These generally persist for only a few hours to several hours, often going unnoticed. During this stage, fluorescein staining produces negative results, while rose bengal staining yields positive results. Necrosis and breakdown of infected epithelial cells result in punctate keratitis. As infected cells release HSV, nearby cells are progressively affected, leading to enlarging lesions. Central epithelial shedding may then develop into dendritic ulcers. These ulcers are characterized by branching termini ending in nodular swellings, surrounded by edematous borders. Fluorescein staining reveals intense green coloration in the ulcer center and a pale green border around the lesion. Active viruses are found in epithelial cells surrounding dendritic ulcers. Severe cases may progress to geographic ulcers.

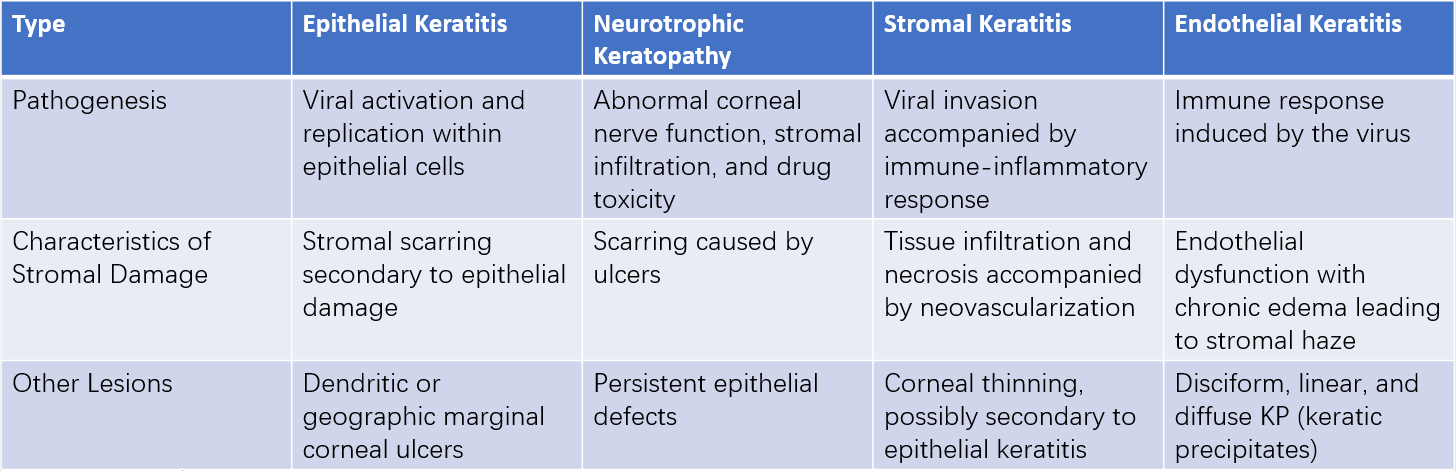

Figure 1 Epithelial herpes simplex viral keratitis

A. The central corneal ulcer appears dendritic, exhibiting a bright green stain under cobalt blue light with sodium fluorescein; the edges of the lesion appear pale green.

B. As dendritic keratitis progresses, geographic corneal ulcers develop.

Epithelial keratitis arises primarily from direct viral destruction of epithelial cells, with minimal immune-mediated inflammation. Histologically, few neutrophils and immune-inflammatory cells are observed in affected tissues.

Reduced corneal sensation is a hallmark of epithelial HSK. Sensory deficits correspond to the extent, duration, and severity of lesions. Although sensation decreases at the lesion site, sensitivity in the surrounding area may be relatively heightened, resulting in symptoms such as pain, irritation, and lacrimation.

Epithelial HSK predominantly affects the epithelial layer or shallow stromal layers. If inadequately controlled, lesions may extend deeper into the stroma, leading to stromal ulceration.

Most cases of epithelial HSK respond well to treatment, often resolving without long-term complications. However, persistent punctate epithelial defects, recurrent epithelial lesions, and epithelial cystic changes may occur. Superficial ulcers generally heal within one to two weeks with appropriate therapy, though resolution of stromal infiltration may take weeks to months and may leave behind corneal opacities with minimal visual impairment.

Neurotrophic Keratopathy

The causes of neurotrophic keratopathy include damage to the basement membrane, reduced tear secretion, and nerve impairment. Toxic effects from antiviral drugs may exacerbate the condition, making the ulcer difficult to heal and potentially leading to corneal perforation in severe cases. Neurotrophic keratopathy often occurs during the recovery or inactive phase of HSK. Lesions may remain localized to the corneal epithelium and superficial stroma but can also extend to the deeper stromal layers. Ulcers typically present as round or oval shapes, mainly in the interpalpebral zone, with mild infiltration and thickened grayish margins.

Stromal Keratitis

Nearly all patients with stromal keratitis have a history of concurrent or previous epithelial keratitis. Based on clinical features, stromal keratitis is classified into two types: immune-mediated and necrotizing.

Immune-Mediated Stromal Keratitis

This is the most common type of herpes simplex keratitis. It manifests with stromal edema, infiltration, and opacity, which may also be accompanied by ingrowth of blood vessels. Folds in Descemet’s membrane may be present. In cases associated with anterior uveitis, keratic precipitates can appear on the endothelium in edematous areas. Recurrent inflammation can lead to scarring, corneal thinning, neovascularization, and lipid deposition.

Necrotizing Stromal Keratitis

This type is characterized by one or multiple yellow-white necrotic stromal infiltrates, stromal dissolution and necrosis, and widespread epithelial loss. Severe cases may present with grayish white abscess-like lesions, keratic precipitates, iridocyclitis, and elevated intraocular pressure. Some patients may also display an immune ring or peripheral vascular inflammation. Stromal lesions result from a combination of active viral infection and immune-mediated inflammation. Necrotizing stromal keratitis often induces stromal neovascularization, appearing as one or more mid-to-deep-layer blood vessels extending from the peripheral cornea toward the central infiltrated area. A small number of cases can lead to rapid corneal thinning and perforation.

Figure 2 Necrotizing stromal keratitis

Yellow-white necrotic infiltrates are present within the corneal stroma, along with stromal dissolution, necrosis, and widespread epithelial defects. Grayish-white abscess-like lesions can be observed.

Endothelial Keratitis

Endothelial keratitis is further divided into disciform, diffuse, and linear types. Its pathogenesis involves a delayed hypersensitivity reaction of the endothelium to viral antigens, with direct viral invasion of endothelial cells also playing a significant role.

Figure 3 Endothelial keratitis

Keratic precipitates are visible on the endothelial surface within the area of corneal edema.

Disciform Endothelial Keratitis is the most common form, presenting with stromal edema in the central or paracentral cornea. The cornea loses its transparency, taking on a ground-glass appearance. Keratic precipitates are present on the endothelial surface in the edematous area, often accompanied by mild to moderate iritis.

Linear Keratitis features endothelial deposits starting from the corneal periphery, accompanied by peripheral stromal and epithelial edema. Intrabecular inflammation may occur and can lead to increased intraocular pressure. Endothelial function typically recovers several months after inflammation subsides, although severe cases may result in irreversible endothelial decompensation.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is established based on clinical history and characteristic findings such as dendritic or geographic ulceration and stromal infiltrates. Laboratory tests can aid in diagnosis, including identification of multinucleated giant cells or intranuclear inclusion bodies through cytology, HSV isolation from corneal lesions, molecular biology techniques, and serological determination of viral antibody titers.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to suppress viral replication within the cornea and mitigate inflammation-induced corneal damage. Different types of HSK require distinct treatment approaches. Epithelial keratitis, caused by viral replication and destruction of epithelial cells, necessitates effective antiviral drugs to halt viral activity and control the disease. Stromal and endothelial keratitis, characterized primarily by immune-mediated inflammation, require both antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatment with corticosteroids. The treatment strategy for neurotrophic keratopathy is similar to that for neuroparalytic corneal ulcers.

Pharmacological Therapy

Common antiviral agents include ganciclovir (GCV) in 0.15% formulations as eye drops or ointments; acyclovir (ACV) as 0.1% eye drops or 3% ointments; and trifluorothymidine at a concentration of 1% as eye drops. Topical ACV has poor corneal penetration and limited efficacy in treating stromal and endothelial keratitis, which is why it is not used in the United States for topical treatment of HSK. Instead, 3% ACV ointment is preferred.

GCV has a higher MIC90 (minimum inhibitory concentration to inhibit 90% of viral activity) compared to ACV by 10 to 100 times, with superior bioavailability, an 8-hour half-life, rapid entry into infected cells, and prolonged retention within virus-infected cells. It has become the first-line treatment for antiviral therapy. Additionally, famciclovir and valacyclovir are also effective against HSK and can be incorporated into treatment regimens.

Patients with severe cases, frequent recurrences, or post-keratoplasty complications may require systemic ACV or GCV for at least two weeks. Those with associated iridocyclitis should be treated with atropine eye drops or ointment to achieve pupil dilation.

Surgical Treatment

Patients with corneal perforation may require penetrating keratoplasty. For those with significant corneal scarring that impairs vision after resolving HSK, corneal transplantation serves as an effective means of restoring sight. Postoperatively, local corticosteroids should be administered along with systemic and topical antiviral therapy to prevent recurrence.

Prevention of Recurrence

HSK has a high recurrence rate, with nearly one-third of recurrences occurring within two years of the primary infection. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) demonstrated that prophylactic oral ACV reduces the recurrence of HSK, particularly in epithelial and stromal subtypes. Oral administration of ganciclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir may also lower the recurrence rate. Managing triggering factors is crucial for minimizing recurrence.