Pterygium refers to fibrovascular tissue connected to the conjunctiva that grows onto the corneal surface, typically occurring on the nasal side of the palpebral fissure. In addition to its impact on appearance, pterygium can induce corneal astigmatism, resulting in visual impairment. When the lesion encroaches on the central optical zone, it can significantly reduce vision.

Etiology

The exact cause and pathogenesis of pterygium remain incompletely understood. Epidemiological studies suggest that ultraviolet (UV) radiation is likely the primary contributing factor. In addition to environmental factors, genetic predisposition also plays an important role, as individuals with a family history of pterygium are more susceptible to its development. Additional factors, such as abnormalities in tear film composition, type I hypersensitivity reactions, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, have also been implicated in its occurrence. Pathological characteristics of pterygium include epithelial dyskeratosis, degeneration of subepithelial collagen fibers and elastic fibers, and substitution of Bowman's layer with hyaline or elastic tissue.

Clinical Manifestations

Pterygium often occurs bilaterally, and lesions on the nasal side are more common. Symptoms are typically absent or limited to mild foreign body sensations. As the lesion extends towards the pupillary zone of the cornea, it can lead to astigmatism or directly obstruct the visual axis, resulting in decreased vision. Hypertrophic fibrovascular conjunctival tissue in the palpebral fissure area grows in a triangular shape onto the cornea. Larger pterygium may also impair ocular motility.

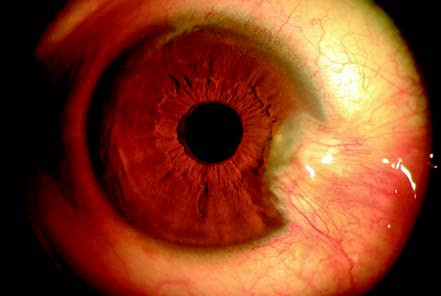

Typical pterygium can be divided into three parts—head, neck, and body—with no distinct boundaries between them. The body usually originates from the bulbar conjunctiva, although in recurrent pterygium, it may also arise from the semilunar fold or the fornix conjunctiva. At the corneoscleral limbus, the body transitions to the neck. The head refers to the portion of the lesion that extends onto the cornea and is tightly attached to the underlying corneal tissue. The presence of Stocker’s line, a pigmented line caused by iron deposition in the epithelium, is often indicative of slow lesion progression. Variations in the appearance of pterygium may reflect different stages of disease progression: in the active phase, the lesion appears hyperemic and thickened, whereas in the quiescent phase, it appears grayish-white, thinner, and membrane-like.

Figure 1 Appearance of pterygium

A yellowish nodular growth extending from the nasal side towards the cornea.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis of pterygium is generally straightforward due to the lesion’s distinctive appearance, but differentiation from other conditions is occasionally required.

Pseudopterygium

Pseudopterygium refers to adhesions between the conjunctiva and cornea caused by trauma, surgery, or inflammation involving the limbal region. Unlike true pterygium, pseudopterygium lacks clearly defined head, neck, and body characteristics. It can occur at any location on the cornea and is often associated with a prior history of trauma or inflammation. Additionally, a probe can often be passed beneath the adhesion in pseudopterygium.

Pinguecula

Pinguecula occurs on the bulbar conjunctiva on either side of the cornea in the palpebral fissure. It presents as a slightly elevated yellowish-white triangular lesion on the conjunctiva and rarely extends onto the cornea.

Conjunctival Tumors

Certain conjunctival tumors may mimic pterygium in their early stages. However, benign tumors typically do not invade the cornea, while malignant tumors exhibit rapid growth, irregular morphology, and potentially invasive behavior. Pathological examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis in such cases.

Treatment

Small and quiescent pterygium generally does not require treatment. Irritants such as wind, sand, and sunlight need to be minimized. Progressive pterygium involving the visual axis may require surgical intervention, though recurrence is a possibility. Surgical techniques include simple pterygium excision, pterygium excision combined with limbal stem cell transplantation, autologous conjunctival grafting, or amniotic membrane transplantation. Combined surgical approaches may help reduce recurrence rates. Postoperatively, topical antibiotics are used to prevent infection, and topical corticosteroids can reduce inflammation, inhibit capillary and fibroblast proliferation, and help prevent recurrence. Artificial tears provide lubrication for the ocular surface, promote tear film restoration, alleviate discomfort, and dilute soluble inflammatory mediators on the ocular surface following pterygium excision.