A carotid body tumor, also known as a chemoreceptor tumor, arises at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. It is a benign and slow-growing tumor, though malignant transformation may occur in rare cases. It can affect individuals of any age or gender. Based on the tumor's anatomical relationship with adjacent blood vessels, carotid body tumors can be classified into three types according to the Shamblin classification:

- Shamblin I: The tumor is relatively small, with minimal attachment to the carotid vessels, and surgical resection is typically less complex.

- Shamblin II: The tumor is usually larger and shows moderate attachment to the artery, but it can still be excised via careful surgical intervention.

- Shamblin III: The tumor is massive and encases the carotid arteries, often requiring vascular replacement during surgery.

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

The carotid body is located at the posterior aspect of the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. It is attached to the arterial wall via connective tissue and varies in size, with an average diameter of about 3.5 mm. It typically appears as a flattened oval or irregularly shaped pink structure. The carotid body is the largest paraganglion in the human body and functions as a chemoreceptor, detecting changes in blood carbon dioxide concentration. Elevated blood carbon dioxide levels lead to a reflexive increase in the rate and depth of respiration.

When a tumor develops in the carotid body, it appears as a reddish-brown, round, or oval mass with a complete capsule. Microscopic examination reveals clusters of tumor cells and a highly vascular stroma. The tumor cells are polygonal with small nuclei.

Clinical Manifestations

The tumor presents as a painless cervical mass located in the carotid triangle. It grows slowly, and the clinical history can extend over several years or even decades. In cases of malignant transformation, the mass may enlarge rapidly over a short period. Smaller tumors are typically asymptomatic or may cause only mild local pressure sensations. Larger tumors may compress adjacent organs and nerves, resulting in symptoms such as hoarseness, dysphagia, tongue muscle atrophy, tongue deviation, dyspnea, and Horner's syndrome.

Diagnosis

A tumor located in the carotid triangle, characterized by slow growth, a relatively hard consistency, clear boundaries, and limited mobility (mobile laterally but restricted vertically), along with palpable vascular pulsation and sometimes audible vascular bruits, should raise suspicion for a carotid body tumor. Diagnostic imaging such as ultrasonography (B-mode ultrasound) and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) has high diagnostic value.

On ultrasonography, the tumor appears as a mass at the bifurcation of the carotid artery, separating the internal and external carotid arteries and increasing the distance between them.

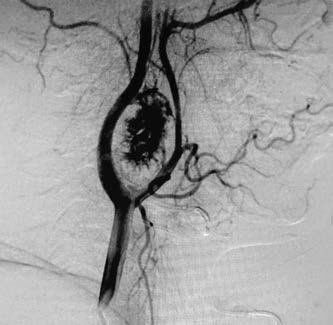

DSA imaging shows the tumor located posterior to the carotid artery, pushing the bifurcation of the common carotid artery anteriorly, with widening of the internal and external carotid branches. The tumor is highly vascular and exhibits a characteristic "lyre sign" on imaging.

Figure 1 DSA of carotid body tumor

Treatment

Surgery is the primary treatment of choice. Given that the tumor originates from the carotid body, which is connected to the adventitia of the carotid artery and has an extremely rich blood supply, as well as its proximity to the carotid artery, veins, and nerves, the procedure poses significant challenges.

In some cases, a multidisciplinary team (MDT), including specialists in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, neurosurgery, and vascular surgery, is needed to optimize the treatment plan. Adequate blood transfusion preparation is essential prior to surgery, and meticulous intraoperative techniques are critical to minimize complications.

For large tumors that are adherent to or encase the carotid artery, the tumor, along with part of the carotid artery, may need to be excised, followed by end-to-end anastomosis of the artery. This type of surgery carries significant risks.