Tracheobronchial foreign body is one of the most common emergencies encountered in the field of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. Delayed treatment can lead to acute airway obstruction, with severe cases resulting in life-threatening complications such as respiratory failure and heart failure. The vast majority of cases occur in children, particularly those between the ages of 1 and 3 years. Elderly individuals and unconscious patients with weakened pharyngeal reflexes are also prone to aspiration, which can result in the occurrence of tracheobronchial foreign bodies.

Based on the origin of the foreign body, they are classified into two categories: endogenous and exogenous. Endogenous foreign bodies include materials such as pseudomembranes, blood clots, crusts, or caseous necrotic material from within the respiratory tract. Exogenous foreign bodies include nuts such as peanuts or sunflower seeds and non-food items such as pen caps, nails, or small toys.

Etiology

The causes of tracheobronchial foreign bodies are associated with various factors, including incomplete physiological and psychological development in children, as well as issues related to caregiving and medical interventions.

In children under the age of 3, the absence of molars prevents effective chewing. Additionally, the lack of coordination in swallowing functions and immature protective mechanisms of the larynx increase the risk of aspiration. School-aged children, who often hold small toys, pen caps, or whistles in their mouths, are at higher risk of inhaling foreign bodies when laughing, crying, or experiencing sudden shock accompanied by deep inhalation.

Inadequate caregiving in the elderly, alcohol intoxication in adults, or aspiration during states of general anesthesia or unconsciousness also contribute to the occurrence of this condition.

Iatrogenic factors, such as the accidental breakage or detachment of medical instruments during tracheal or bronchial surgery, can result in the introduction of foreign objects into the trachea. Similarly, excised tissue fragments can slide into the airway, and foreign bodies in the oral cavity or nasal passages may shift unexpectedly during medical procedures, leading to aspiration into the lower respiratory tract.

Endogenous foreign bodies, such as those caused by conditions like plastic bronchitis or granulation tissue, can also contribute.

Pathology

The pathophysiology associated with tracheobronchial foreign bodies is closely related to the type, nature, size, shape, location, duration of retention, and degree of obstruction caused by the foreign body.

Type and Nature of the Foreign Body

Foreign bodies can be classified into categories such as plant-based, animal-based, metallic, and synthetic materials. Plant-based foreign bodies, such as peanuts and legumes, contain free fatty acids that strongly irritate the airway mucosa, causing severe acute diffuse inflammatory reactions of the respiratory tract mucosa, a condition clinically referred to as "vegetative tracheobronchitis." In contrast, foreign bodies made of materials like glass, stainless steel, or alloys exert minimal irritation and provoke milder pathological reactions.

Size and Shape of the Foreign Body

Small smooth foreign bodies cause less irritation but can migrate with airflow. Larger foreign bodies, or those with sharp or irregular shapes, are more likely to cause tissue damage, leading to complications such as mediastinal emphysema, granulation tissue formation, or fibrosis.

Location of the Foreign Body

Foreign bodies that are lodged in the glottis or subglottic region can cause significant symptoms of upper airway obstruction. Foreign bodies retained in one bronchus, if relatively fixed in position, may not result in symptoms of respiratory distress.

Duration of Retention

Longer retention times increase the potential harm, especially for foreign bodies with irregular surfaces or strong irritant properties. This can lead to recurrent pneumonia, bronchiectasis, or pulmonary abscesses.

Degree of Obstruction

The degree of bronchial obstruction caused by the foreign body leads to varying pathophysiological changes. Jackson (1936) classified the bronchopulmonary pathological effects of bronchial foreign bodies due to mechanical obstruction into four types:

- Partially Obstructive Type: In this type, air can partially flow in and out of the narrowed area around the foreign body, resulting in partial bronchial obstruction.

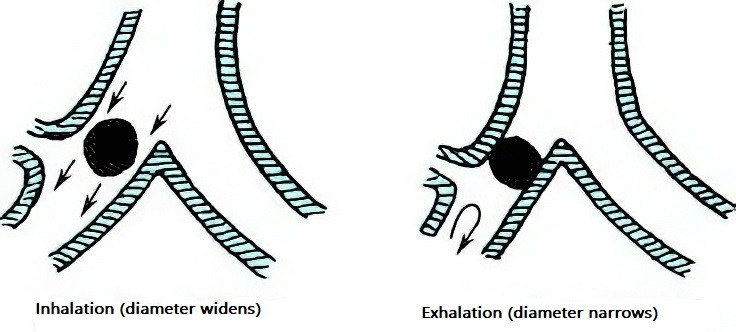

- Inspiratory Valve Obstruction (Check-Valve Type): The position of the foreign body allows air to enter during inhalation when the bronchial lumen expands and a gap forms between the foreign body and the airway wall. However, during exhalation, the foreign body is pushed by airflow to seal the bronchial lumen, preventing air from escaping. This results in emphysema distal to the foreign body in the affected bronchus.

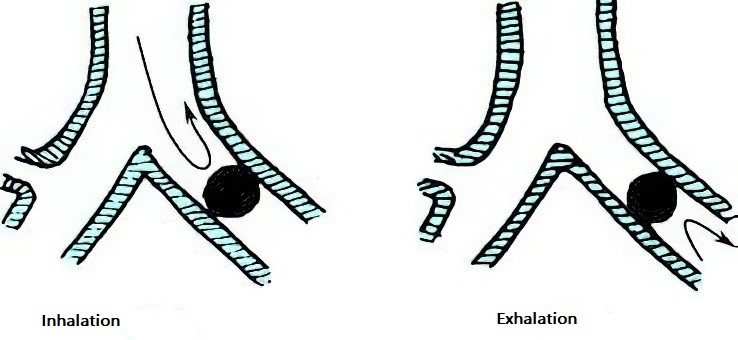

- Expiratory Valve Obstruction (Reverse Check-Valve Type): Air can exit but cannot re-enter due to the positioning of the foreign body, leading to atelectasis distal to the foreign body. This can also cause compensatory emphysema in an adjacent lung lobe or the contralateral lung.

- Complete Obstruction Type: Complete obstruction prevents both air entry and exit, resulting in obstructive atelectasis.

Figure 1 Partial obstruction type (causing pulmonary emphysema)

Figure 2 Complete obstruction type (causing pulmonary atelectasis)

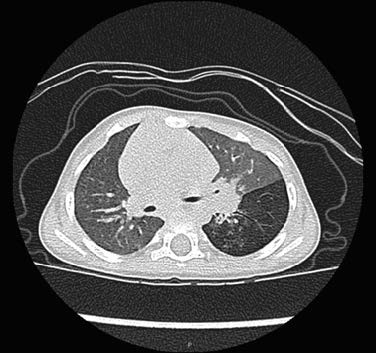

Figure 3 Horizontal CT scan of the lungs showing left lower lobe pulmonary emphysema with medial inflammatory pulmonary lesions

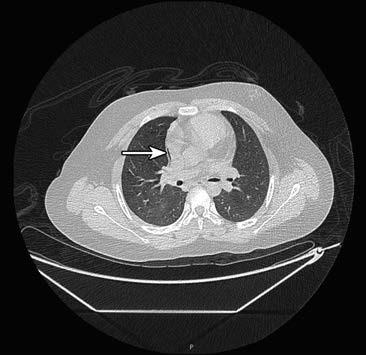

Figure 4 Coronal CT scan of the lungs showing left bronchial foreign body causing left-sided pneumonia and atelectasis

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms

Tracheal Foreign Body

During the entry phase, symptoms are severe and occur suddenly, including violent coughing, breathlessness, retching, difficulty breathing, and even suffocation. Characteristic symptoms include sounds of impact, a sensation of striking, and wheezing. Persistent or paroxysmal coughing is common.

Bronchial Foreign Body

Symptoms can vary greatly. In some cases, a foreign body may remain in the bronchus for years without causing symptoms, but if the foreign body obstructs both bronchi, it may lead to asphyxia and death within a short period.

Four stages can be identified based on the course of the condition:

- Foreign body entry stage: Symptoms include choking cough, inspiratory stridor, breathlessness, retching, and spasmodic respiratory distress.

- Asymptomatic stage: The duration varies depending on the nature of the foreign body and the degree of infection. Diagnosis during this stage is challenging due to atypical symptoms, increasing the risk of missed or incorrect diagnoses.

- Symptom recurrence stage: The foreign body induces irritation and infection, leading to an inflammatory response, increased secretions, exacerbated coughing, respiratory inflammatory reactions, or symptoms such as high fever.

- Complication stage: Complications such as pneumonia, atelectasis, asthma, bronchiectasis, or pulmonary abscess appear.

Physical Signs

Tracheal Foreign Body

Mobile foreign bodies in the neck's trachea may produce impact sounds and stridor. Lung auscultation may reveal symmetrical yet weakened bilateral breath sounds, along with dry or moist crackles and wheezing. During neck palpation, a sensation of vibration caused by the foreign body may be detected.

Bronchial Foreign Body

On inspection, the affected side of the chest may show reduced respiratory movement. If atelectasis occurs in one lung, chest wall retraction may be observed. Tactile fremitus on the affected side may decrease. Percussion may produce hyperresonance if obstructive emphysema is present or dullness if atelectasis occurs. Auscultation of the lung may reveal diminished breath sounds on one side and a mix of crackles or wheezing. Foreign bodies with sharp edges that damage the bronchial walls may lead to complications such as mediastinal emphysema or pneumothorax.

Figure 5 Mediastinal emphysema on the right side caused by a foreign body (arrow)

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The majority of cases are not difficult to diagnose based on a clear history of foreign body aspiration, along with characteristic clinical symptoms, physical signs, and imaging studies.

Medical History

A clear history of foreign body aspiration is critical for diagnosing respiratory foreign bodies. Cases involving sudden-onset coughing, chronic coughing unresponsive to treatment, or recurrent episodes after initial improvement, as well as recurrent pneumonia or pulmonary abscess in the same region, should raise suspicion of possible foreign body aspiration.

Physical Examination

General examination should assess for any signs of breathing difficulty or life-threatening conditions such as heart failure. Tracheal foreign bodies may produce glottic impact sounds during coughing or at the end of exhalation, which may also be accompanied by a palpable sensation of striking in the neck. Early bronchial foreign body cases may present with subtle physical findings. Comparison of breath sounds between the two sides of the lungs should evaluate for asymmetrical breath sounds, wheezing, and other indicative signs, including findings related to complications such as pneumonia, atelectasis, and emphysema.

X-ray Examination

Metallic foreign bodies appear clearly on radiographs, allowing for determination of their location, size, and shape. Radiolucent foreign bodies may be inferred through indirect signs. When a tracheobronchial foreign body is suspected, chest radiography in both anterior-posterior and lateral projections is performed, along with fluoroscopy of the chest.

Figure 6 X-ray showing a metallic foreign body in the left bronchus

Continuous observation of the entire respiratory cycle during fluoroscopy provides significant diagnostic insights. Relevant findings include:

- Mediastinal swing: Partial obstruction of one bronchus by a tracheal foreign body leads to imbalanced pressure between the two pleural cavities. This causes the mediastinum to shift toward one side during inhalation and the other side during exhalation. If a fixed expiratory valve mechanism develops, obstructed air egress leads to emphysema in the affected lung, increasing its intrapulmonary pressure and displacing the mediastinum toward the healthy side. Conversely, a mobile foreign body may cause an inspiratory valve mechanism, resulting in reduced air entry, atelectasis, and mediastinum displacement toward the affected side, which becomes more noticeable during inhalation.

- Pulmonary emphysema: The affected lung shows increased transparency, elevated intrapulmonary pressure, and a lowered diaphragm.

- Atelectasis: Affected lung segments or lobes exhibit increased density, reduced volume, lowered intrapulmonary pressure, an elevated diaphragm, and inward mediastinal displacement, with no changes during respiration.

- Pulmonary infection: Findings include patchy, unevenly dense, and blurred infiltrates.

Chest CT

CT imaging may reveal evidence such as intra-tracheal foreign bodies, hyperdense opacity, pulmonary emphysema, or atelectasis, all of which are considered positive findings. Three-dimensional reconstruction can provide insights into the continuity of the bronchial tree and indications of discontinuity caused by the foreign body. Simulated virtual imaging facilitates visualization of the foreign body's contour, size, and location, as well as its relationship with the bronchial mucosa and surrounding tissues. Multi-slice CT (MSCT) achieves a diagnostic accuracy rate as high as 99.8% for tracheobronchial foreign bodies.

Fiberoptic (or Electronic) Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy remains one of the diagnostic gold standards for tracheobronchial foreign bodies. It enables direct visualization of the foreign body, including its size, shape, nature, and anatomical location.

Clinically, tracheal and bronchial foreign bodies should be differentiated from other respiratory conditions, such as asthma, airway-occupying lesions, and other respiratory tract diseases.

Treatment

Tracheal and bronchial foreign bodies pose life-threatening risks, and removal of the foreign body is the only effective treatment. Therefore, the primary treatment principle is early removal of the foreign body to prevent asphyxia and other respiratory complications.

The likelihood of expelling a tracheal or bronchial foreign body through coughing is very low, making surgical removal the only definitive treatment. The presence of a foreign body in the trachea or bronchus can cause sudden asphyxia, threatening the patient's life. Immediate removal is necessary. For patients with complications such as pneumonia or heart failure, these conditions should be managed before surgery. If the foreign body is mobile and causing breathing difficulties, surgery should be performed without delay.

Adequate and accurate preoperative evaluation should precede the removal of a tracheal or bronchial foreign body. This includes planning the treatment strategy, selecting the appropriate surgical timing, and minimizing complications. Preoperative evaluations focus on assessing vital signs, respiratory status, associated complications, and anesthesia risks.

Surgical Methods for Removing Tracheal and Bronchial Foreign Bodies

Removal via Direct Laryngoscopy

This approach is suitable for foreign bodies lodged in the vestibule or glottis. When clamping a foreign body to remove it through the glottis, the clamp's opening should be aligned so that the widest diameter of the foreign body is parallel to the glottic opening. This reduces the risk of the foreign body becoming stuck or dislodging while passing through the narrow glottis.

Rigid Bronchoscopy for Foreign Body Removal

This method is used for foreign bodies in the trachea, main bronchi, or segmental bronchi. The procedure is generally performed under general anesthesia. The patient lies supine with their head tilted backward. An assistant supports the head and adjusts its position as needed. Aided by video-assisted endoscopy, the foreign body is visualized and removed with appropriate forceps. During bronchoscopy, secretions in the airway should be suctioned continuously to ensure smooth operation.

Flexible (Electronic) Bronchoscopy for Foreign Body Removal

This method is advantageous for removing foreign bodies located in deep bronchi, such as the upper lobe bronchi and the posterior basal segment of the lower lobe bronchi. As advancements in flexible bronchoscopy technology continue, its applications have expanded from deep bronchi to include foreign bodies in the trachea and left or right primary bronchi.

Tracheotomy-assisted foreign body removal: Certain situations necessitate the removal of foreign bodies via tracheotomy:

- Large foreign body: Foreign bodies too large to be removed effectively through the glottis (e.g., large pearls that repeatedly slip when passing through the glottis) pose a risk of asphyxia if further attempts are made.

- Large or uniquely shaped foreign body: Foreign bodies such as dentures that are difficult to remove through the glottis under bronchoscopic guidance.

- Foreign bodies with unique shapes: Foreign bodies that may cause significant glottic damage during removal through the glottis.

Foreign Body Removal via Thoracoscopy or Thoracotomy

In situations where the risks of endoscopic removal exceed those of thoracic surgery, thoracoscopy or thoracotomy may be required. Postoperative care should follow the standard protocol for thoracic surgery. These situations include:

- Foreign bodies located deep in the lung that are beyond the reach of the bronchoscope and cannot be retrieved.

- Irregularly shaped foreign bodies that cannot be mobilized or retrieved using a bronchoscope (e.g., dentures, nails, or other metallic objects), or foreign bodies that may cause severe damage during bronchoscopic manipulation (e.g., glass shards, blades, or bone fragments).

- Long-standing foreign bodies in the bronchus, significant inflammatory granulation tissue obstructing the airway or encasing the foreign body, or severe adhesions making endoscopic removal unsuccessful. Forced removal in such cases carries a high risk of severe complications.

Complications

Laryngeal and Bronchial Spasm

Laryngeal or bronchial spasm can result from irritation caused by the foreign body, repeated airway manipulation, hypoxia, or carbon dioxide retention. The incidence of spasm is higher with anesthesia methods that preserve spontaneous breathing. It is necessary to address the underlying cause, deepen anesthesia, elevate the mandible, and relieve respiratory distress through positive pressure ventilation using a face mask or endotracheal intubation.

Pneumothorax, Mediastinal Emphysema, and Subcutaneous Emphysema

Pneumothorax and mediastinal emphysema are dangerous complications. If they do not compromise surgical safety, the foreign body should still be removed as soon as possible. In cases of respiratory distress, heart failure, or pneumothorax, immediate needle decompression is required at the second intercostal space along the midclavicular line, followed by consultation with thoracic surgery for prompt closed thoracic drainage. For mediastinal or subcutaneous emphysema, subcutaneous puncture or mediastinal drainage may be necessary.

Intratracheal Hemorrhage

Chronic irritation by the foreign body often leads to mucosal inflammation, swelling, congestion, and a tendency for bleeding. The longer the condition persists, the more likely bleeding becomes. Excessive bleeding can obscure the surgical field and complicate the removal of the foreign body. The administration of 1:10,000 epinephrine solution into the trachea can help reduce bleeding.

Acute Respiratory Failure

Respiratory arrest may occur during the removal of the foreign body. If respiratory and cardiac arrest occurs upon the insertion of a laryngoscope to expose the glottis, laryngospasm caused by vagal reflex is often the underlying cause, which in turn affects cardiac function. High-volume oxygen delivery to the glottis, high-frequency ventilation, intubation, or insertion of a tracheoscope may be required to restore normal ventilation. The application of 1% lidocaine spray to the larynx before inserting the laryngoscope can prevent laryngospasm.

Respiratory and cardiac arrest may also occur during the procedure as a result of the foreign body shifting position and causing bilateral bronchial obstruction, which leads to ineffective gas exchange and respiratory failure. Respiratory and cardiac arrest represent the most dangerous complication and are the leading causes of mortality, highlighting the urgency of immediate resuscitation. Detailed preoperative evaluation of cardiopulmonary function and preparation for monitoring and emergency management, alongside the use of general anesthesia, can help prevent such emergencies.

Pneumonia and Atelectasis

Pneumonia and atelectasis resulting from airway obstruction and secondary infection are generally treatable with antibiotic therapy following foreign body removal. For long-standing foreign bodies, especially in cases of atelectasis with large amounts of purulent exudate in the trachea and bronchi, intraoperative bronchial and alveolar lavage with saline can promote lung re-expansion and resolution of inflammation.

Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Tracheoesophageal fistula, a rare complication of respiratory foreign bodies, requires vigilance for its postoperative symptoms. Patients may exhibit recurrent coughing and sputum production, with worsening symptoms, cyanosis, and exacerbated coughing after eating or drinking. Larger fistulae may result in the regurgitation of food debris. Bronchography, esophagography, fiberoptic (or electronic) bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, or chest CT can help identify the location and size of the fistula and its relationship with surrounding tissues.

Severe Systemic Complications

Systemic complications include extensive subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, pyopneumothorax, mediastinal infection, pneumonia, and sepsis.

Prognosis

This condition is highly dangerous. Complete obstruction of the glottis or trachea due to a lodged foreign body can result in sudden death. Delayed diagnosis and treatment may lead to complications such as bronchitis, bronchiectasis, emphysema, atelectasis, pneumonia, pulmonary abscess, spontaneous pneumothorax, mediastinal emphysema, or subcutaneous emphysema. Early diagnosis and timely removal of the foreign body generally allow for rapid recovery of airway and lung pathologies.

For long-standing foreign bodies, even after removal, the associated destructive changes may require a prolonged period for full recovery.

Prevention

Respiratory foreign bodies are among the most common causes of accidental injury in children but are largely preventable. Public education should be enhanced to raise awareness of the risks and prevention strategies associated with this condition.

Avoiding the consumption of nuts such as peanuts, sunflower seeds, and beans by children under the age of three is important.

Laughing, crying, or engaging in scolding or disruptive behavior should be minimized while eating or with food in the mouth.

Children should be taught not to play with food or toys in their mouths, while adults should refrain from holding foreign objects in their mouths when performing other tasks.

Enhanced care for unconscious or general anesthesia patients is necessary to prevent the aspiration of vomitus into the lower respiratory tract.