Tracheal intubation is an effective emergency procedure used to quickly relieve upper airway obstruction, ensure airway patency, suction lower respiratory secretions, and provide assisted ventilation.

Indications

Acute Respiratory Failure

Conditions such as neonatal asphyxia, acute infectious laryngeal obstruction, respiratory distress caused by compression of the larynx and trachea by neck masses, or pre-insertion of a tracheal tube prior to an emergency tracheotomy to alleviate respiratory distress.

Critical Conditions

Loss of airway protective reflexes, such as in comatose patients; patients with severe respiratory dysfunction; or those with severe circulatory dysfunction, such as cardiac arrest.

General Anesthesia Surgery

Situations requiring artificial or mechanical ventilation assistance.

Equipment

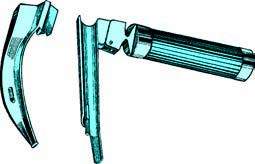

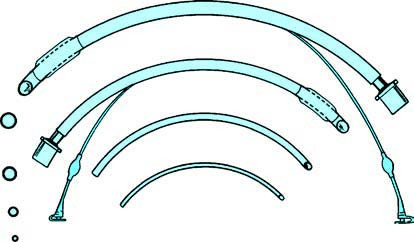

Appropriate anesthetic laryngoscopes and tracheal tubes are selected based on the patient's age and individual characteristics. Tube specifications are defined by inner diameter (ID), ranging from 2.0 to 9.0 mm.

Figure 1 Anesthetic laryngoscope

Figure 2 Various models of tracheal tubes

Neonates typically require tubes with ID 2.0–3.0 mm.

For children:

- Under 1 year: ID 3.5–4.0 mm

- 1–2 years: ID 4.5 mm

- 3–4 years: ID 5.0 mm

- 5–6 years: ID 5.5 mm

- 7–9 years: ID 6.0 mm

- 10–14 years: ID 6.5–7.0 mm

For adults:

- Females: ID 7.0–8.0 mm, with a general insertion depth of 21 cm.

- Males: ID 7.5–9.0 mm, with a general insertion depth of 23 cm.

Procedure

The process can be categorized into orotracheal and nasotracheal intubation.

Anesthesia

Topical anesthesia is commonly performed by spraying 1%–2% tetracaine onto the nasal, pharyngeal, and laryngeal areas. In emergency situations or pediatric cases, anesthesia may not be administered. The procedure is typically performed with the patient in a supine position.

Orotracheal Intubation

A gauze pad is placed on the upper incisors to protect the teeth. The practitioner holds the anesthetic laryngoscope or video laryngoscope in the left hand and inserts it into the pharynx, positioning it in the vallecula to lift the epiglottis and expose the glottis. Using the right hand, the practitioner advances the tube (with a metal stylet inside) through the glottic opening into the trachea. After confirmation of insertion into the trachea, the stylet is removed, the tube is adjusted to the appropriate depth, and it is secured to the cheek along with the bite block.

Nasotracheal Intubation

An appropriate tube is selected, lubricated, and inserted through the nasal cavity into the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and larynx into the trachea. If difficulties arise, a laryngoscope may be used for visual guidance to insert the tube through the glottis. This method is easier to secure, does not interfere with swallowing, but is technically more challenging. A nasal mucosal vasoconstrictor can be used in advance if necessary.

Guided Intubation Using a Rigid Video Stylet or Fiberoptic Scope

For challenging airways, such as those with mandibular deformities, limited mouth opening, cervical spine disease, or trauma where glottic visualization is difficult, intubation can be performed under the guidance of a rigid video stylet or a fiberoptic bronchoscope, either orally or nasally.

After the intubation, the chest is compressed to check for airflow at the tube's opening to confirm its placement in the trachea. Additional verification can include observing bilateral chest rise during mechanical ventilation, auscultating bilateral lung sounds, or observing the appearance of "white mist" in the tube during exhalation.

Complications

In patients with difficult airways, repeated attempts at intubation without clear visualization of anatomical landmarks may lead to complications, such as injury to the larynx, vocal cords, or trachea. This can result in mucosal damage, edema, vocal cord granulation, or cricoarytenoid joint dislocation. Severe cases may lead to laryngeal or tracheal stenosis.

To minimize complications, practitioners should have proficient intubation skills and select appropriately sized tubes. The duration of tube retention should not exceed 48–72 hours. Excessive balloon cuff inflation should be avoided, and if the clinical condition allows, the cuff can be relaxed for 5–10 minutes every hour to prevent localized tissue necrosis caused by compression.