Laryngeal obstruction, also referred to as laryngeal blockage, occurs when pathological changes in the larynx or adjacent tissues lead to obstruction of the laryngeal airway, resulting in breathing difficulties. Laryngeal obstruction is one of the common emergencies in otolaryngology and head and neck surgery, and delayed treatment may result in asphyxiation and death. Due to their smaller laryngeal cavity, loose submucosal tissue, and susceptibility of laryngeal nerves to spasmodic stimulation, children experience laryngeal obstruction more frequently than adults.

Etiology

The causes include:

- Inflammation: Conditions such as acute laryngitis in children, acute epiglottitis, acute laryngotracheobronchitis, laryngeal diphtheria, laryngeal abscess, and deep neck space infections.

- Trauma: Laryngeal contusions, incised wounds, burns, or inhalation of toxic gases or high-temperature steam.

- Edema: Angioneurotic edema of the larynx, food- or drug-induced allergic reactions, and edema associated with cardiac or renal diseases.

- Foreign Bodies: Foreign bodies in the pharynx, larynx, or trachea may not only cause mechanical obstruction but also induce laryngeal spasms.

- Tumors: Tumors of the pharynx and larynx, recurrent papillomatosis of the larynx and trachea, and thyroid tumors.

- Malformations: Congenital issues such as laryngomalacia, laryngeal webs, laryngeal cartilage deformities, and laryngeal scar stenosis.

- Vocal Cord Paralysis: Bilateral vocal cord paralysis caused by various underlying factors.

Clinical Manifestations

Inspiratory Dyspnea

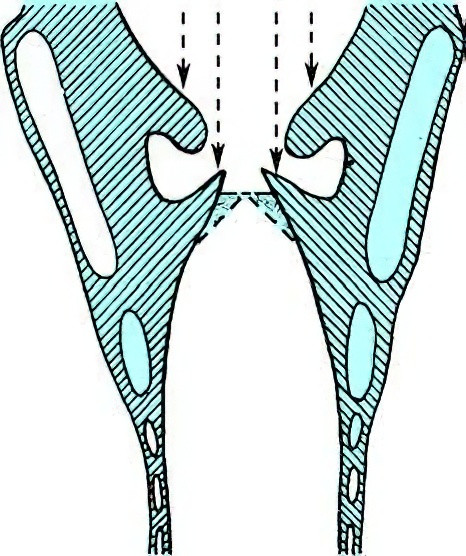

Inspiratory dyspnea is the primary symptom of laryngeal obstruction. The glottis, the narrowest part of the laryngeal airway, is formed by the upward-slanting edges of the vocal cords. During inspiration, airflow pushes the slanted vocal cords downward and inward. Under normal conditions, simultaneous abduction of the vocal cords allows the glottis to widen, maintaining adequate airflow. When the glottis narrows, hypoxemia accelerates respiratory movements, increasing airflow speed through the glottis and exacerbating inward and downward displacement of the vocal cords during inspiration. This further reduces the cross-sectional area of the airway, creating a vicious cycle of inspiratory dyspnea and hypoxia. The condition is characterized by stronger and prolonged inspiratory movements, with deep and slow breaths, but without a corresponding increase in ventilation. If oxygen levels remain sufficient, the respiratory rate may not change. During expiration, airflow pushes the vocal cords outward and upward, allowing the glottis to slightly widen, enabling exhalation, and thus expiratory difficulty is less prominent.

Figure 1 Diagram illustrating the mechanism of inspiratory dyspnea during laryngeal obstruction

Inspiratory Stridor

Stridor during inspiration occurs as the narrowed glottis causes turbulent airflow, which vibrates the vocal cords, creating the characteristic sound. The intensity of the stridor correlates with the degree of obstruction, and severe cases produce loud stridor that can be heard even from adjacent rooms.

Inspiratory Soft Tissue Retraction

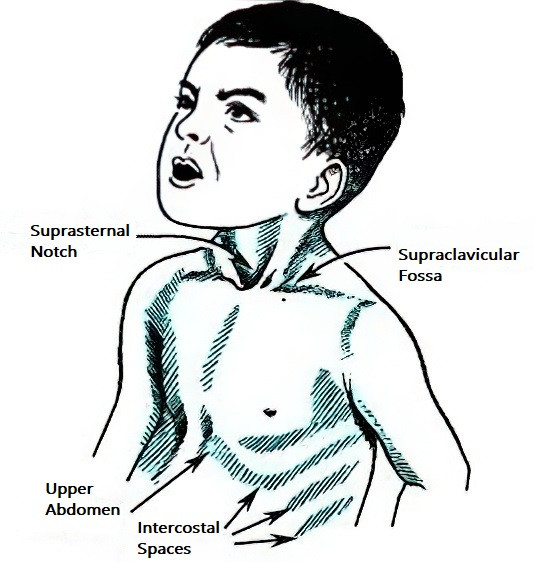

During inspiration, when airflow struggles to pass through the glottis and enter the lungs, the accessory respiratory muscles of the chest and abdomen contract compensatorily to expand the thoracic cavity. The inability of the lungs to inflate adequately increases intrathoracic negative pressure, pulling the thoracic wall and its surrounding soft tissues inward. Retraction areas include the suprasternal notch, supraclavicular and infraclavicular fossae, and intercostal spaces, which may sink inward during inspiration, forming the "three-retraction sign." Severe cases may also exhibit retraction below the xiphoid or in the upper abdominal region. The severity of the retraction correlates with the degree of respiratory difficulty. This sign is particularly pronounced in children due to relatively weak muscle tone.

Figure 2 Inspiratory soft tissue retraction

Hoarseness

Lesions involving the vocal cords can result in hoarseness or even aphonia (loss of voice).

Cyanosis

Hypoxia may cause cyanotic discoloration of the face. Symptoms during inspiration may include head tilting backward, restlessness while sitting or lying, and difficulty sleeping. In the late stages, symptoms such as weak and rapid pulse, arrhythmias, cold sweats on the forehead, heart failure, and eventual coma and death may occur.

Examination

The severity of laryngeal obstruction is classified into four grades:

- Grade I: No respiratory distress at rest. Mild inspiratory dyspnea, slight inspiratory stridor, and minimal soft tissue retraction around the chest during activities or crying.

- Grade II: Mild inspiratory dyspnea, inspiratory stridor, and soft tissue retraction around the chest during rest. Symptoms worsen with activity but do not interfere with sleep or eating, and signs of hypoxia, such as restlessness, are absent. Pulse remains normal.

- Grade III: Significant inspiratory dyspnea, loud inspiratory stridor, pronounced soft tissue retraction, and hypoxia-related symptoms such as restlessness, difficulty sleeping, reduced appetite, and rapid pulse.

- Grade IV: Extreme respiratory distress. Patients exhibit severe restlessness, limb movement, cold sweats, pallor or cyanosis, disorientation, arrhythmias, weak and rapid pulse, coma, incontinence, and other critical signs. Without timely intervention, asphyxiation may lead to cardiac and respiratory arrest and death.

Diagnosis

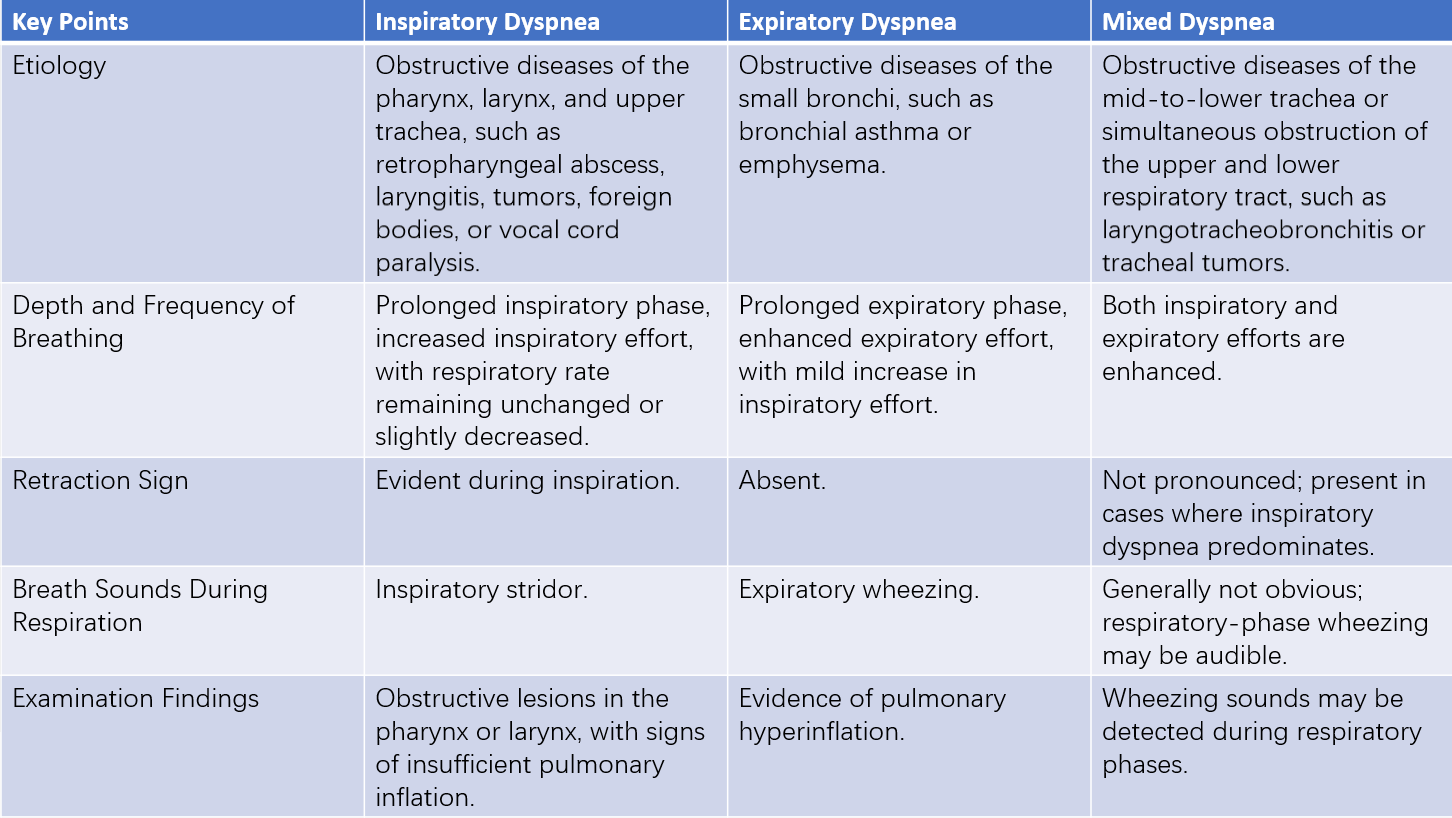

The diagnosis of laryngeal obstruction is generally not difficult when considering the patient's medical history, symptoms, and signs. The primary focus lies in identifying the underlying cause. For patients with severe respiratory distress, alleviating their breathing difficulties takes priority before conducting further examinations to determine the etiology. Differential diagnosis is necessary to distinguish laryngeal obstruction from expiratory or mixed-type dyspnea caused by conditions such as bronchial asthma and tracheobronchitis.

Table 1 Key points for differentiating three types of obstructive dyspnea

Treatment

Laryngeal obstruction in acute cases requires urgent intervention to quickly alleviate breathing difficulties to prevent asphyxiation or heart failure. Treatment varies based on the underlying cause and the severity of respiratory distress and may involve either pharmacological or surgical approaches.

Grade I

Identifying the cause and addressing it forms the main approach. For inflammation-related cases, sufficient doses of antibiotics and corticosteroids are used.

Grade II

In cases caused by inflammation, effective antibiotics and corticosteroids in adequate doses are often sufficient to avoid tracheostomy. For foreign body obstruction, removal is prioritized. In situations where immediate removal of the underlying cause is not possible, such as with laryngeal tumors, laryngeal trauma, or bilateral vocal cord paralysis, tracheostomy may be considered.

Grade III

For obstruction caused by inflammation with a short duration, close monitoring with proactive use of medication is emphasized, and preparation for tracheostomy is made. If medical treatment does not yield improvement, or if the patient’s general condition deteriorates, early tracheostomy is advisable. In cases involving tumors, tracheostomy is indicated.

Grade IV

Immediate tracheostomy is required. In critically urgent cases, cricothyrotomy may be performed as a preliminary step.

Etiological treatment may, in certain circumstances, be instituted initially, such as removal of a laryngeal foreign body or incision and drainage of a retropharyngeal abscess. However, for critically ill patients, tracheostomy should take precedence. After relieving respiratory distress, specific treatment targeting the underlying cause can then be administered.