Laryngocele, also known as laryngeal pouch or laryngeal diverticulum, is a pathological dilation of the laryngeal saccule that contains air.

Etiology

Both congenital and acquired factors contribute to the formation of laryngocele:

Congenital Factors

The laryngeal saccule originates from the anterior portion of the laryngeal ventricle and is located between the thyroid cartilage and the base of the epiglottic cartilage. In infants, the laryngeal saccule is relatively large, generally measuring around 6–8 mm, but in some cases may reach 10–15 mm. Congenital abnormal enlargement of the saccule can lead to the formation of a congenital laryngocele.

Acquired Factors

Anomalies in the development of the saccule, combined with chronic straining activities such as persistent coughing, blowing musical instruments, glassblowing, or weightlifting, increase the pressure within the larynx. This elevated pressure gradually enlarges the saccule, leading to laryngocele formation.

Valvular Mechanism

Edema or stenosis at the opening of the saccule can create a one-way valvular effect, trapping air inside the saccule, which expands to form a laryngocele.

Specific Infections

Infectious diseases of the larynx, such as laryngeal tuberculosis or laryngeal syphilis, may also result in laryngocele.

Clinical Manifestations

Laryngocele is classified into internal, external, and mixed types:

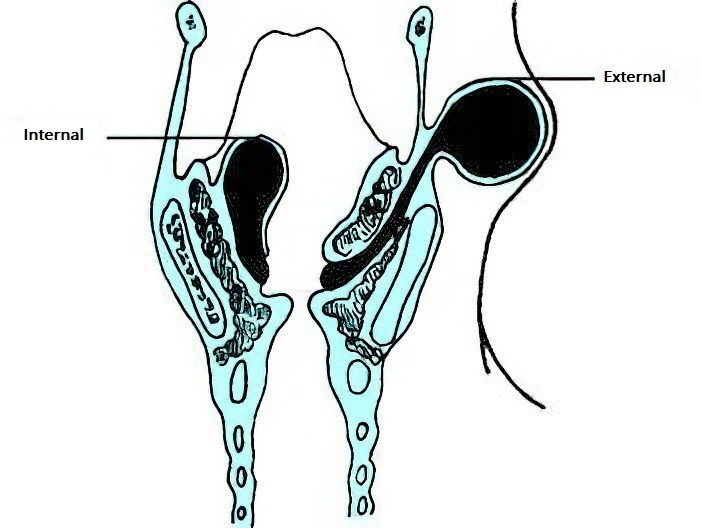

Figure 1 Laryngocele

Internal Type

This type arises from the laryngeal ventricle, protruding into the laryngeal cavity. It can push the ventricular band medially and upward to cover the vocal folds or may protrude from the aryepiglottic fold toward the laryngeal cavity. Smaller lesions are often asymptomatic, while larger ones may cause symptoms such as hoarseness, coughing, and respiratory difficulty. Pain is possible if infection occurs.

Laryngoscopic examination reveals bulging of one ventricular band, obstructing the ipsilateral vocal fold and partially blocking the glottis. The size of the lesion changes with respiration, decreasing during inhalation and increasing when forcefully exhaling or straining.

External Type

The air-filled cyst protrudes upward from the laryngeal saccule, passing through the thyrohyoid membrane near the superior laryngeal nerve and vessels, and presents as a bulging mass on the neck. The primary symptom is a round, fluctuating, cystic mass on the neck that enlarges and shrinks intermittently. The mass becomes smaller with manual compression.

Mixed Type

This type involves both the laryngeal cavity and the neck, with the two portions connected through a narrow isthmus at the thyrohyoid membrane, creating a dumbbell shape. Clinical features of both internal and external types are present.

Diagnosis

External and Mixed Types

Diagnosis is primarily based on symptoms, physical findings, and imaging studies of the neck. The presence of a soft, compressible cystic mass that shrinks upon palpation, alongside the aspiration of air during needle puncture, confirms the diagnosis.

Internal Type

Careful observation during laryngoscopy is essential, with attention to changes in the size of the lesion during respiration. Reduction in size during inhalation and enlargement during forceful exhalation or straining are key diagnostic features. Compression of the mass causing it to shrink further supports the diagnosis. High-resolution CT can provide precise localization and determine the size and extent of the cyst.

Differential Diagnosis

Internal Type

Differentiation is necessary from laryngeal ventricle prolapse and congenital laryngeal mucus cysts. Laryngeal ventricle prolapse often results from inflammatory mucosal edema or hyperplasia, protrudes from the laryngeal ventricle, and does not change size with respiration. Congenital laryngeal mucus cysts, found mainly in infants, result from saccular dilation with mucus retention and lack communication with the laryngeal cavity.

External Type

This type must be distinguished from branchial cleft cysts and thyroglossal duct cysts. Laryngoceles differ as they are compressible, vary in size, and contain air shadows on imaging, while other types of cysts lack these features.

It is also important to consider that conditions such as laryngeal tuberculosis, laryngeal chondritis, or laryngeal cancer may present with associated laryngocele. Thorough examination is crucial to avoid misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis.

Treatment

Surgical excision is the preferred approach for managing laryngocele. For smaller internal laryngoceles, endoscopic removal using CO2 laser or laryngeal splitting techniques may be performed. For larger internal, external, or mixed laryngoceles, the external cervical approach is employed to dissect and excise the cyst, with ligation if necessary.

In cases of respiratory distress, immediate puncture of the cyst or tracheotomy may be required.

If infection occurs, careful observation is essential regardless of whether airway obstruction is present. Effective antibiotics should be administered, with preparation for tracheotomy if needed. Abscess formation requires incision and drainage first, with definitive excision carried out after the infection is controlled.