Motor neurological disorders of the larynx refer to vocal cord mobility impairments caused by damage to the motor nerve conduction pathways governing the intrinsic muscles of the larynx. Since the vagus nerve and the recurrent laryngeal nerve are mixed nerves containing both sensory and motor fibers, both types of nerve fibers are often affected simultaneously. Isolated sensory or motor nerve damage occurring independently is extremely rare in clinical practice.

Dysfunctions of laryngeal muscles and sensory impairments caused by damage to the vagus nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve, or superior laryngeal nerve are collectively referred to as laryngeal paralysis, as they present with adduction-abduction impairments of the vocal cords and sensory deficits of the larynx. This condition is more commonly termed vocal cord paralysis (also known as vocal cord palsy). It primarily manifests as hoarseness, respiratory distress, swallowing difficulties, and aspiration, significantly impacting the patient’s quality of life and, in severe cases, posing life-threatening risks.

Etiology

The etiology of laryngeal nerve paralysis is complex. Any disruption along the laryngeal motor nerve conduction pathway may lead to this condition. The causes are broadly categorized into central lesions and peripheral lesions, with the latter being more common. Since the left vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves have a longer course than the right, the left side is more frequently affected.

Central Causes

The motor neuronal center for the larynx is located in the nucleus ambiguus, while the cortical motor center for the larynx is connected bilaterally to the nucleus ambiguus via neural tracts. Because each side of the laryngeal motor circuit receives impulses from both hemispheres, cortical damage rarely causes laryngeal paralysis. Central lesions that may lead to laryngeal paralysis include cerebral hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson's disease, medullary tumors, syringobulbia, and thrombosis of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery. Damage to the intracranial segment of the vagus nerve can also result in laryngeal paralysis.

Central damage can be further divided into upper motor neuron and lower motor neuron lesions. Common conditions affecting upper motor neurons include Parkinsonism, progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, Shy-Drager syndrome, pseudobulbar palsy, multiple sclerosis, and myoclonus. Common lower motor neuron disorders include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Wallenberg syndrome (lateral medullary syndrome), and post-polio syndrome.

Peripheral Causes

Damage to any part of the vagus nerve after it exits the brainstem or along the pathway of the recurrent laryngeal nerve to the intrinsic muscles or sensory areas of the larynx can result in laryngeal paralysis. Peripheral causes can be classified as follows:

Trauma

For example, skull base fractures, neck trauma, and iatrogenic injuries from procedures such as thyroid surgery, thoracic or mediastinal surgery, and lateral skull base surgery.

Tumors

Tumors such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, metastatic neck malignancies, thyroid tumors, and carotid body tumors can compress or invade the vagus nerve or recurrent laryngeal nerve. In the thoracic cavity, the recurrent laryngeal nerve may be compressed or invaded by conditions like aortic aneurysms, lung cancer, or esophageal cancer.

Inflammation

Infectious diseases like diphtheria or influenza, heavy metal poisoning, rheumatism, measles, and syphilis can cause peripheral neuritis of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Idiopathic Causes

Demyelinating neuropathies of unclear origin can also lead to idiopathic laryngeal paralysis.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of peripheral recurrent laryngeal nerve damage depends on the nature, severity, and duration of the injury. Most patients experience varying degrees of natural regeneration of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, referred to as subclinical reinnervation. The extent of subclinical reinnervation determines the position of the paralyzed vocal cord and the appearance of the vocal cords and glottis. Laryngeal paralysis is commonly classified into unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, superior laryngeal nerve paralysis, idiopathic recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, mixed nerve paralysis, and combined nerve paralysis.

Unilateral Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Paralysis

This condition primarily manifests as varying degrees of hoarseness, often accompanied by coughing or aspiration. Symptoms are usually more severe in the early stages and tend to improve over time. Respiratory distress does not typically occur.

In early stages, indirect or electronic laryngoscopy shows a paralyzed vocal cord fixed in a paramedian position, caused by complete paralysis of both the adductor and abductor muscles. In later stages, movement may be restricted or the vocal cord may remain variably fixed between the paramedian and median positions. During phonation, the glottis may not close completely, and during inhalation, the affected vocal cord may fail to abduct. The position and movement alterations of the vocal cord over time are due to partial recovery of nerve function in some patients. Adduction and abduction functions of the vocal cord may partially return in some cases, while in others, abduction may remain limited, but adduction function may recover to some extent. This asymmetry is due to the fact that adductor fibers of the recurrent laryngeal nerve outnumber abductor fibers by a factor of three, leading to a higher degree of natural regeneration in the former.

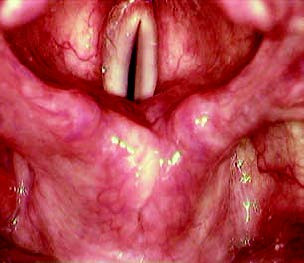

Figure 1 Phonation phase in complete left recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis

Figure 2 Inspiration phase in complete left recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis

Even when only adduction recovery or partial recovery of both adduction and abduction occurs, the condition is referred to as incomplete vocal cord paralysis. In some cases, there is no recovery of vocal cord movement at any level, and the cord remains entirely immobile, which is classified as complete vocal cord paralysis. This condition can be further divided into two types:

The nerve injury is relatively mild, and subclinical reinnervation ensures that the vocal cord is fixed near the median or midline position. In such cases, the contralateral vocal cord compensates by adducting past the midline, leading to glottic closure during phonation. Voice quality remains normal or near normal.

The nerve injury is more severe, resulting in poor subclinical reinnervation. The paralyzed vocal cord becomes fixed in positions ranging from near the paramedian to the median position, accompanied by significant cord atrophy. Under laryngoscopic observation, the cord appears thin, bowed, and shortened.

Bilateral Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Paralysis

Bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis primarily presents with respiratory distress as the main symptom, often accompanied by hoarseness and coughing. In the early stage, laryngoscopy reveals both vocal cords fixed in the paramedian position due to paralysis of both adductor and abductor muscles. In later stages, the cords may remain fixed in positions ranging from the paramedian to the median, with varying degrees of glottic closure. The vocal cords may fully close during phonation or remain completely open, depending on the specific presentation of complete bilateral vocal cord paralysis. The inability to abduct the cords during inhalation or the presence of reduced abduction amplitude, along with glottic closure during phonation, may indicate incomplete bilateral vocal cord paralysis.

Different presentations in later stages are influenced by factors such as the selective involvement of abductor branches or the comparatively easier recovery of the adductor branches following nerve damage. The position of the fixed vocal cords depends on the nature of the nerve injury, the duration of the condition, the extent of damage, and the degree of natural nerve regeneration. In the early stage, damage to both the abductor and adductor branches of the recurrent laryngeal nerve causes the cords to be fixed in the paramedian position. Over time, nerve reinnervation favors the adductor muscles, causing the cords to gradually migrate toward the median position. During this phase, hoarseness may improve while respiratory distress worsens. Superimposed upper respiratory infections or inflammation can lead to airway obstruction or even asphyxia. In cases of bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, some patients initially experience little or no respiratory difficulty, but as natural nerve recovery progresses, the cords can migrate medially, leading to progressive respiratory distress or even asphyxia. A small proportion of cases may show a delayed onset of respiratory symptoms, with the interval between nerve injury and the first occurrence of respiratory distress ranging from several years to decades.

Superior Laryngeal Nerve Paralysis

This condition is often caused by iatrogenic injury, such as during thyroid surgery, and results in the loss of vocal cord tension. Patients are unable to produce high-pitched sounds and may present with coarse, weak voices and shortened phonation times. In unilateral paralysis, contraction of the contralateral cricothyroid muscle rotates the anterior edge of the cricoid cartilage toward the affected side and its posterior edge toward the contralateral side, causing glottic asymmetry. Laryngoscopic examination may reveal an angled glottis, with the anterior commissure deviating toward the healthy side and the posterior commissure toward the affected side. The affected vocal cord appears wrinkled, with a wavy edge. However, adduction and abduction remain normal. In bilateral paralysis, impaired sensation of the laryngeal mucosa increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

Idiopathic Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Paralysis

This condition refers to vocal cord paralysis with no identified cause, such as trauma or tumors. Bilateral manifestations are rare. The onset is often acute, with a history of upper respiratory infection. The pathological mechanism may involve demyelinating neuropathy. Clinical manifestations are consistent with those seen in vocal cord paralysis.

Mixed Nerve Paralysis

This condition refers to concurrent injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the superior laryngeal nerve. Symptoms include hoarseness and an inability to produce high-pitched sounds, frequently accompanied by coughing. In the early stage, laryngoscopy may reveal the affected vocal cord fixed in the intermediate position due to paralysis of the cricothyroid, adductor, and abductor muscles. In the later stages, the cord's position depends on the degree of natural nerve regeneration following injury. Electromyography often suggests impairments in both the recurrent laryngeal and superior laryngeal nerves.

Combined Nerve Paralysis

This condition involves recurrent laryngeal nerve injury accompanied by damage to the posterior group of cranial nerves (glossopharyngeal nerve, hypoglossal nerve, and accessory nerve). It is commonly caused by tumor involvement or trauma in regions such as the skull base or jugular foramen. In addition to the signs and symptoms of recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, patients may exhibit deficits associated with posterior cranial nerve injury, such as weakened elevation of the soft palate, uvula deviation, tongue deviation, and atrophy of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of laryngeal paralysis is primarily based on clinical manifestations and findings from relevant auxiliary examinations. Medical history, physical examination, endoscopic evaluation, and imaging studies are all indispensable components. In addition, laboratory tests are useful for ruling out specific causes of laryngeal paralysis. Auditory-perceptual evaluation and acoustic parameter analysis of voice assist in differentiating between neurogenic and functional voice disorders. Dynamic laryngoscopy provides insight into the vibratory characteristics of the vocal cords. High-speed photography, ultrasound, fluoroscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging also hold significant diagnostic value. Spontaneous and evoked laryngeal electromyography is considered the gold standard for diagnosing vocal cord paralysis, offering additional value in determining whether the damage is central or peripheral in origin.

Quantitative analysis of the aforementioned parameters allows for the documentation of disease status and progression, assessment of the severity and trajectory of the condition, selection of treatment strategies, and evaluation of therapeutic outcomes. It is important to determine whether the underlying cause of laryngeal paralysis is central or peripheral nerve injury. Further analysis is necessary to identify the causes of peripheral nerve damage. The condition must also be differentiated from the following disorders:

Arytenoid Cartilage Dislocation

This condition is often associated with a history of general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation or neck trauma. Laryngoscopic examination may reveal fixation of the affected vocal cord. The two vocal cords may not lie in the same plane, and the two laryngeal ventricles may exhibit asymmetry, with the ventricular fold on the affected side potentially protruding. Stroboscopic laryngoscopy findings may include reduced or absent mucosal waves and weakened movement amplitude of the vocal cord on the affected side. Thin-slice CT imaging of the larynx may confirm arytenoid cartilage dislocation. While electromyography findings in such cases may exhibit characteristics of recurrent laryngeal nerve damage, the severity is typically mild.

Cricoarytenoid Arthritis

This condition is usually a localized manifestation of systemic joint diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or gout. It may also result from conditions such as laryngitis or chondritis extending to the cricoarytenoid joint, often seen in streptococcal infections, or may occur as a secondary effect of acute infectious diseases like typhoid fever and influenza. Radiation therapy can also lead to cricoarytenoid arthritis. Acute cricoarytenoid arthritis is relatively easier to diagnose, with symptoms such as throat pain, hoarseness, congestion, and swelling in the arytenoid cartilage area. Diagnosis often relies on the observation of a triangular glottic gap during phonation. The severity of hoarseness and respiratory difficulty varies depending on the degree of inflammation and the position of vocal cord fixation. Chronic cricoarytenoid arthritis may closely mimic recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, but differentiation can be aided by palpation of the arytenoid cartilage and laryngeal electromyography.

Cricoarytenoid Joint Injury

This condition is often secondary to laryngeal trauma and may lead to loss of arytenoid cartilage mobility. Vocal cords may present in abduction, paramedian, or median positions. Dynamic laryngoscopy demonstrates abnormalities in vocal cord vibration symmetry, periodicity, amplitude, and mucosal wave patterns. Laryngeal electromyography findings are generally normal. Palpation of the arytenoid cartilage may reveal fixed or stiff cricoarytenoid joints with poor mobility. Surgical exploration can reveal findings such as joint edema or adhesions of the articular surfaces.

Head and Neck Tumors

Hypopharyngeal carcinoma and cervical esophageal cancer may invade regions such as the pyriform sinus, postcricoid area, and arytenoid region. Symptoms include localized swelling in the arytenoid region, and vocal cords often exhibit partial paralysis.

Myasthenia Gravis

This is the most common neuromuscular junction disorder. When it involves the muscles of the pharynx and larynx, symptoms can include hoarseness, weak phonation, and swallowing difficulties. A characteristic feature is the worsening of symptoms later in the day and improvement after rest. Laryngoscopy may show reduced vocal cord movement during phonation, an incomplete glottic closure, and decreased mucosal wave activity. Laryngeal electromyography is of significant diagnostic value in identifying this condition.

Treatment

The treatment principles include identifying the underlying cause and addressing it, improving or restoring vocal function, relieving breathing difficulties, and preventing complications.

Etiological Treatment

Treatment involves identifying the underlying cause and implementing targeted therapeutic measures to address and resolve it. Systemic or localized administration of neurotrophic agents such as vitamin B12 or thiamine disulfide, along with drugs that improve microcirculation, may be beneficial. In some cases, corticosteroid therapy may aid in the recovery of nerve function.

Speech Therapy

Speech therapy can be applied to patients with central nervous system lesions, potentially improving voice quality to some extent. It can also be beneficial for individuals with unilateral peripheral laryngeal paralysis. For patients requiring surgical intervention, speech therapy serves as a valuable interim approach during the waiting period, contributing to overall rehabilitation.

Surgical Treatment

Several considerations need to be addressed regarding surgical intervention:

- An observation period of at least six months is necessary. For vagus nerve injuries, skull base trauma, or idiopathic vocal cord paralysis, the observation period may extend to nine months or longer before surgery can be considered if recovery is not achieved.

- Surgical methods should be determined based on the underlying cause, type of paralysis, disease duration, severity, patient preferences, and overall health condition.

- After the observation period, if symptoms persist and conditions permit, early surgical intervention with recurrent laryngeal nerve repair should be performed.

- Prompt management is required for complications of vocal cord paralysis, such as laryngeal obstruction, aspiration, or significant coughing.

Unilateral Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Paralysis

For confirmed cases of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury where causal treatment, medication, and observation fail to restore function, recurrent laryngeal nerve repair is typically the first consideration. Ansa cervicalis–recurrent laryngeal nerve anastomosis, particularly involving the primary branch of the ansa cervicalis or its anterior root, is often the procedure of choice. Other options include branch-level anastomosis or direct end-to-end recurrent laryngeal nerve anastomosis. Muscle pedicle grafts or nerve implantation from the ansa cervicalis are generally not employed independently.

For nerve injuries of longer than three years, combined procedures are often required, such as ansa cervicalis–recurrent laryngeal nerve anastomosis with type I thyroplasty or arytenoid medialization. Such frameworks address the less ideal outcomes of isolated nerve repair in chronic cases. Vocal cord injection augmentation, using materials like autologous fat or artificial substances, is another option. Laryngeal framework surgeries are commonly employed to treat unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, including arytenoid medialization, type I thyroplasty, or a combination of both. Arytenoid medialization is more suitable for cases with significant posterior glottic gaps, while type I thyroplasty is recommended for bowing vocal cords or larger anterior glottic gaps.

Bilateral Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Paralysis

The treatment of bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis is particularly challenging and primarily aims to relieve airway obstruction while preserving phonatory function as much as possible. Common surgical methods include vocal cord lateralization procedures via extra-laryngeal or intra-laryngeal approaches, arytenoidectomy with lateralization using CO2 lasers or plasma radiofrequency techniques, and conventional approaches such as tracheostomy or surgical creation of a tracheostomal opening. These procedures often sacrifice vocal function and may increase the risk of aspiration.

Selective recurrent laryngeal nerve repair is theoretically the most ideal approach. Current techniques involve combined nerve repair for adductor and abductor function, aiming to restore the physiological movement of the vocal cords with abduction during inhalation and adduction during phonation. However, these procedures are technically complex and require strict selection for surgical indications. Optimal results are achieved when the patient is under 60 years of age, and the duration of the condition does not exceed one year prior to surgery.